After a rather long hiatus, and while we wait for the long anticipated final version of Narasimhan et al. (hopefully out very soon), here’s a quick post commenting on a few things that have been published lately.

Tracking Five Millennia of Horse Management with Extensive Ancient Genome Time Series

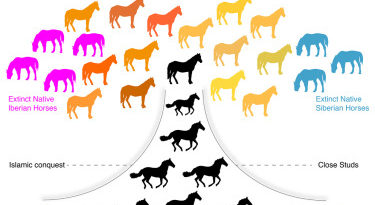

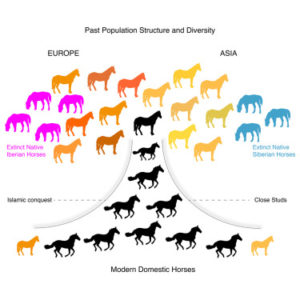

A follow up to their previous paper, briefly commented on a previous post, that brings some new information about the history of domestic horses, though far from clarifying things it makes everything less clear opening new questions. Here is their graphical abstract:

And the key findings regarding early history of domestication:

- Two now-extinct horse lineages lived in Iberia and Siberia some 5,000 years ago

- Iberian and Siberian horses contributed limited ancestry to modern domesticates

These newly found extinct lineages of early domestic horses add to the Botai ones, which didn’t go extinct but apparently went feral and survive in the form of Przewalski horses, as found in an even earlier paper (Gaunitz et al. 2018).

So let’s start to look at this puzzle and try to put a few pieces together. We have a horse lineage in Siberia living up until 5000 years ago that didn’t contribute any significant ancestry to the main (and for a long time the only) domestic lineage. Then we have another lineage further west, in Kazakhstan, that was domesticated c. 3500 BC but that also didn’t contribute much to main domestic horses. And finally we have a lineage in Iberia that we domesticated somewhere in the late Chalcolithic, and while it seems to have been used for a while as an early domestic horse in Europe it also ultimately went extinct without contributing much to the main domestic lineage.

A closer look at the data from this latter Iberian lineage brings us some additional interesting information: There is a sample from 2600 BC (note that this predates the arrival of R1b/steppe people) belonging to this domestic lineage (native to Iberia). But then another Iberian samples from 1900 BC (note that his is 500 years after the arrival of R1b/steppe Bell Beaker folk) is still of the same kind. Furthermore, a sample from Hungary c. 2100 BC shows some 12% admixture from this Iberian lineage (the rest of its makeup being from main domestic horses and another unknown lineage).

What this suggests is something rather surprising: R1b/steppe Bel Beakers don’t seem to have carried horses with them to Western Europe. Otherwise those would have largely replaced the local Iberian ones. Instead, it seems that Bell Beaker horses were those who they found in Iberia and might have traded with them all the way to Hungary. Indeed, this comes to reinforce the scarce evidence for the use of domestic horses in EBA steppe related cultures. Not much evidence in the Corded Ware Culture (for example, domestic horses only arrived to the east Baltic in the Iron Age, in spite of the area being occupied by early CWC population).

So where did domestic horses come from? That’s the min question right now. Traditionally, the Pontic-Caspian steppe has been the main candidate for it. However, the previous paper from this same team, based on climatic simulations and found remains, seemed to discard that area as suitable for horses at the time of probable domestication. Now this new study adds to that hypothesis by providing no evidence of the people coming from that area to Europe in the early 3rd mill. bringing their own domestic horses. Unfortunately, this study had 2 or 3 samples that could represent the Pontic-Caspian steppe wild horses, but they all yielded a very low amount of endogenous DNA to be included in any autosomal analysis. So that question remains open.

The thing is that the first good evidence of clear and extensive use of domestic horses of the main lineage comes from Sintashta, c. 2000 BC. So where did those horses came from? It’s unlikely that they were local, given the proximity with the Botai Culture area (and in west Siberia), where we know that very divergent lineages existed. To me it seems that they could have arrived there from anywhere. And it might not be that relevat after all. The place where the main domestic lineage originated might be rather unimportant, given that for all we know this domestication seems to have occurred quite later than first thought (closer to 2500 BC than to the previously suggested 3500 BC), and it may have been the Sintashta people the first ones who found a real use for them, no matter where they got them from. Whatever the case, it seems that the history of domestic horses is also turning out to be quite different from what was previously thought. Hopefully the next paper before the year’s end will shed some light in all of this.

Whole-genome sequencing of 128 camels across Asia provides insights into origin and migration of domestic Bactrian camels

Lian Ming et al. 2019 (preprint)

This one is a modern DNA study dealing with the domestication fo the Bactrian camel. Though I’m not sold on their idea that Bactrian camels were domesticated 10.000 year ago, the rest of the hypothesis looks good (as far as modern DNA can be informative). An image and a few excerpts summarise it well.

The origin of domestic dromedaries was recently revealed by world-wide sequencing of modern and ancient mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which suggested that they were at first domesticated in the southeast Arabian Peninsula [11]. However, the origin of domestic Bactrian camels is still a mystery. One intuitive possibility was the extant wild Bactrian camels were the progenitor of the domestic form, which were then dispersed from the Mongolian Plateau to west gradually [7, 12].

[…]Another possible place of origin was Iran [1], where early skeletal remains of domestic Bactrain camels (around 2,500-3,000 BC) were discovered [14].

[…]The wild Bactrian camels made also little contribution to the ancestry of domestic ones. Among the domestic Bactrian camels, those from Iran exhibited the largest genetic distance from others, and were the first population to separate in the phylogeny. Although evident admixture was observed between domestic Bactrian camels and dromedaries living around the Caspian Sea, the large genetic distance and basal position of Iranian Bactrian camels could not be explained by introgression alone. Taken together, our study favored the Iranian origin of domestic Bactrian camels, which were then immigrated eastward to Mongolia where the native wild Bactrian camels inhabited.

[…]This scenario could well resolve the mystery why the wild and domestic Bactrian camels from the Mongolian Plateau have so large genetic distance.

[…]Despite the insights gleaned from our data, it was important to note that the direct wild progenitor of domestic Bactrian camels were not found in Iran now, which may no longer exist.

[…]In future work, sequencing of ancient genomes from camel fossils will add to the picture of their early domestication.

Not much to add, really. They looked with an extensive set of modern camel DNA at the two different scenarios proposed for domestication and concluded that their data favoured the Iranian one, in spite of wild camels no longer existing in Iran, contrary to Mongolia (where they exist but are very divergent from domestic ones, just like the horses).

We’ll wait for ancient DNA to either confirm or deny this.

The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene

I already commented quite extensively on the very interesting and well written paper when the preprint was out last year. Now it’s been finally published and hopefully the genomes will be made available (if they aren’t already). I was glad to see that the only problem I found with the preprint (their hypothesis about ANS surviving somewhere in Beringia and mixing with East Asian populations to form the Native American one, which seemed to me incompatible with the genetic data presented, due to Native Americans sharing more alleles with Malta and AfontovaGora3 than with the Yana samples) has been addressed in the final versions:

For both Ancient Palaeo-Siberians and Native Americans, ANS-related ancestry is more closely related to Mal’ta than to the Yana individuals (Extended Data Fig. 3f), which rejects the hypothesis that the Yana lineage contributed directly to later Ancient Palaeo-Siberians or Native American groups.

So unfortunately for them, these Yana population seems to have died out during the LGM, something not too surprising when such climatic event catches you in the Arctic.

“I’m more intrigued by other claims that apparently Niraj Rai made in some interview about upcoming papers (hopefully before the end of the year), so let’s see what they have.” —- Yeah, there are two upcoming papers, one on different R1a clades in modern indian pops and the other one on analysis of horse remains dated to mature harappan .

@Alberto

Nevermind, I was referring to the supplements. The samples in question are contaminated.

By the way, since the Italy papers are coming soon, what do you think the haplogroup situation will be?

It’ll be the first instance of a clearly non-IE population living next to a clearly IE population, so the differences between the Etruscans and the Italics will be interesting.

My prediction is that the Italics differ from the Etruscans in that they carry Bronze Age Near Eastern Y-DNA, the populations being otherwise broadly similar where they neighbour each other.

@ Marko

Yep it sounds pretty awesome with 12,000 years of samples; but still 1-2 months away (?)

“Rome as a genetic melting pot: Population dynamics over 12,000 years

Nearly 2000 years ago, Rome was the largest urban center of the ancient world and the capital of an empire with over 60 million inhabitants. Although Rome has long been a subject of archaeological and historical study, little is known about the genetic history of the Roman population. To fill this gap, we performed whole genome sequencing on 127 individuals from 29 sites in and around Rome, spanning the past 12,000 years. Using allele frequency and haplotype-based genetic analyses, we show that Italy underwent two major prehistoric ancestry shifts corresponding to the Neolithic transition to farming and the Bronze Age Steppe migration, both prior to the founding of the Roman Republic. As Rome expanded from a small city-state to an empire controlling the entire Mediterranean, the city became a melting pot of inhabitants from across the empire, harboring diverse ancestries from the Near East, Europe and North Africa. Furthermore, we find that gene flow between Rome and surrounding regions closely mirrors Rome’s geopolitical interactions. Interestingly, Rome’s population remains heterogeneous despite these major ancestry shifts through time. Our study provides a first look into the dynamic genetic history of Rome from before its founding, into the modern era.”

It sounds like truly that the city of Rome became cosmopolitan; & hence the differences between non- IE & IEs in Italy will be a challenging riddle; as elsewhere ; which will mostly fall on a steppe /MNE cline

@Rob

I guess to be particularly relevant to question of IE origins Italic is simply too late. I was hoping for additional samples from Anatolia and also from the shaft graves, but I guess we won’t be seeing these anytime soon.

I hope we also get some samples from southern Italy.

Edit: from the abstract it sounds like the authors might not have done a proper autosomal analysis.

Marko

The data from the study looks fine. Yes more samples are needed; but I don’t think it’ll suggest that PIE came from Mesopotamia

@Rob

Do you still think the eastern Balkanic/western Anatolian area looks best for Indo-Hitttite? I can’t make much sense of the data we have thus far to be honest.

Marko,

It’s still difficult to clearly characterise the details because there were several to / fro movements in the Black Sea zone; at least 2 neolithic waves followed by 2 or 3 ‘waves’ back to Anatolia. However, broadly speaking I think there is evidence to suggest I-H emerging somehwere around there; with nuclear I.E. beginning to expand more readily c. 2500 BC from a locus further north

On Narasimhan 2019, Paul Heggarty’s “Indo-European and the Ancient DNA Revolution” – https://www.academia.edu/40316071/Indo-European_and_the_Ancient_DNA_Revolution – seems to be online (perhaps it was before and I missed it).

He’s rather playing catch up with the adna, which tends to make him unfortunate from the view of the sphere of adna led arguments about linguistic spread (even these are, in truth, generally simplistic association of a language with a particular ancestry component without allowing for switching, or as he says “To repeat from §1.1, then, there is no expectation of any exclusive, one-to-one association between linguistic lineages and genetic ones … And a single language lineage like Indo-European need not have a unique, clear-cut genetic profile — as it clearly does not. So hypotheses do not stand or fall on simplistic one-to-one associations between languages and genes.”).

But I think his commentary on Narasimhan’s paper (which has not in truth been affected by the recent print over the print) seems to bear repeating given the topic:

“Indeed further east, as noted in §3.1, although modern populations of South Asia do show some ancestry from the Steppe, it is much more limited in scale, especially relative to the Eastern Fertile Crescent (EFC) component. In fact, the first ancient DNA samples have now emerged from cultures originally assumed by some advocates of a Steppe origin of Proto-Indo European (see Mallory 1989, Bryant 2001) as candidates for having brought Indo-Iranic into South Asia, namely BMAC and/or the Gandhara Grave culture. Narasimhan et al. (2018) report that the BMAC samples in fact show negligible Steppe ancestry and cannot be the source of this in South Asia. They therefore push the chronology later, in a model of migrations in which a contribution of Steppe ancestry is first detected as late as 3200 BP in Iron Age samples from the Swat Valley, and builds up there only progressively… or a correspondence with the linguistics, it is above all on the chronological level that these findings from Central and South Asia bear consequences for the Indo-European origins debate. Many other supporters of a Steppe origin have of course long argued (on the basis of ‘chariotry’ vocabulary, for example) that Indo-Iranic expansion south of the steppe does indeed date only to as late as the Middle and Late Bronze Age. That Steppe ancestry is not found in BMAC, and entered South Asia only in more recent periods still, would seem coherent with that. Yet it only highlights the linguistic counter-argument, too: that this brings us forward into a time-frame too recent to sit well alongside the scale of language divergence across and even within the Iranic, Nuristani and Indic branches. Moreover, the positions of Iranic and Indic within the PCA plot in Damgaard et al.’s (2018a) figure 2b continue to appear straightforwardly compatible with the alternative scenario proposed in §3: the branch ancestral to Indo-Iranic spread eastwards with farming from Neolithic Iran. The later impacts detected from the Steppe via Central Asia would then not have succeeded in introducing a major new language lineage in Persia and South Asia. Their demographic impacts seem too small and too gradual to have plausibly brought about the near total replacement of all native languages across the huge region of Indo-Iranic speech. The BMAC culture, then, far from the early suggestion than it may have acted as a conduit for Steppe influences southwards into Iran and South Asia, may instead have been what brought ancient Iranian ancestry (mostly EFC ) to spill over northwards into Central Asia. There it admixed (in roughly balanced proportions) with local populations with significant East Asian ancestry, to give rise to the ancestry profiles of many of the “Scythian” groups in Damgaard et al.’s (2018b) extended data figures 1d and 1e. This scenario is likewise broadly compatible with the new ancient DNA findings and analyses in Narasimhan et al. (2018).”

As expected his argument is that the late movement of steppe ancestry into Swat and to Turan and South Asia in general is inconsistent with the time depths reconstructed internally within Iranic, Indic, Nuristani by the Bayesian Phylogenetic methods for which he and Gray and Greenhill have made quite strong arguments for (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328696049_Bayesian_Phylolinguistics), and he postulates a reverse scenario…

@Matt

Exactly. Heggarty beats me to the punch in some respects. What is going on is fascinating.

Thanks for posting the links above.

Heggarty might very well be the guy.

@Matt

Thanks for sharing that. I couldn’t read the paper yet, but it’s good to see such implication from linguists with aDNA studies. IIRC Heggarty was already commenting about the papers from 2015 (Allentoft et al. and Haak et al.) where the big steppe migration was uncovered with arguments about steppe ancestry being highest in Uralic speakers. Those were probably too early times to debate about languages on the basis of aDNA and we were all probably making too simplistic arguments one way or another. But I guess that after some years we’re all a bit wiser and his current views are probably much better founded. In the end it’s good that more specialists take advantage of the new data coming out and try to propose new models based on it.

It’s really interesting that in parallel to the aDNA developments there is this linguistic one based on collecting large datasets from all the available languages and find ways to analyse it with the help of computational tools. Once all the databases are complete and publicly available I’m sure that many people will be able to play around with them and figure out interesting things.

Thanks Matt, I will read in spare time.

I have great respect for Reich and even Vagheesh, but the apply Ocams razor with abnormal bias against parsimony, to 7000 odd years of Human history spanning continents. Chances are that you have discarded the main signals of interest with such an approach.

There is no one to one mapping between Bronze-Age language families and the much older neolithic autosomal components. The first PIE speakers themselves would not been “autosomally pure” as per our artificial definitions.

Anatolian and Iran Neolithic were long standing neighboring populations with extensive mixing across their core respective areas.

If pressed, either of them or a hybrid could serve as the initial founding PIE population which itself is an idealization. In fact there could have been multiple extinctions, borrowings and spreading events and no one would know the difference.

Similarly Central Europe can also be a candidate for PIE or late PIE especially if we use the GAC like signal in steppe-MLBA as the germ that differentiates “true IE ” vs non IE speakers in the Indian subcontinent and ignore the larger autosomal components.

Theres something fundamentally wrong in such knee jerk associations.

I once tried to articulate this to Vagheesh but his mind is very set. I respectively submit that Effectively Reich and company are Steppe-tards. Perhaps the steppe hypotheses has a good deal of truth but this is not the way to propagate it.

So rumors are that even some of the Samnites were autosomally like Cretans/Cypriots. Oh well.

I’m open about “models”, but in terms of sociolinguistics and paleo linguistics; Heggarty should be a go to for understanding

But I didn’t quite understand in Vageesh’s final paper. They suggest that the finding of ‘native’ Iran HG ancestry in India rulenout his model; but what & when is his model exactly ? Isn’t there a West Asian admixture in Turan during the eneolithic ..

I believe part of Heggarty’s theory was that farmers from the Near East introduced farming to NW India through population movements across Iran plateau.

If that stands ruled out, then steppe hypothesis must be ruled out as well by the same logic as Anatolia BA has no steppe ancestry.

Vasishta

Thanks . On both accounts we should await further sampling.

Matt: Thx for the Heggarty link. I think it makes sense to read it in conjunction with his more fundamental considerations back from 2015:

https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315794013.ch28

There, he a/o speaks out against “prestige language” and “elite dominance” models:

Like Swahili still today (Wald 2009: 885–886), many lingue franche count far more second-than first-language users. This leaves them highly susceptible to their apparent (but only second-language) ‘expansion’ collapsing back in on itself once circumstances change: witness ‘The Death of Sanskrit’ (Pollock 2001) across South-East Asia, and the declines of many once widespread lingue franche of the Mediterranean (Phoenician, Greek, ‘Sabir’) or the eastern coast of Africa (Arabic, Portuguese, Swahili), none of which established itself as a first language across the whole region. Where trade and religion are not accompanied by more formal and powerful conquest-type expansions, clear cases of language replacement seem relatively few.(..)

The expected linguistic correlate of trade — or of cultural contacts of other forms — is by no means necessarily an expansion of one particular language, which replaces others as a native tongue and then diverges into a family. In the many periods and areas where contacts between neighbouring groups operate ‘down-the-line’ on more local scales, rather than by long-distance trading voyages, the likely linguistic result is effectively the opposite. For speakers can interact through the corresponding linguistic pattern: rolling, localised bilingualism (or multilingualism) in a chain of different languages linking across geographical space. Their languages do converge on each other, in loanwords and eventually in broader typological characteristics, but they remain genealogically distinct. The outcome is not a language family but a linguistic area, broad but loosely defined, over core and periphery zones. Such is a plausible scenario for how linguistic areas arose in Amazonia or the early Central Andes, for example. (..)

In pre-Modern times, dominant elites in fact time and again conspicuously failed to spread their own language; rather, it was they who assimilated linguistically to the demographic majority they had conquered. Among a wide range of known historical examples are: the speakers of Turkic and Mongolic who became the Mughals in India, and the Yuan Dynasty in China; all known incursions from the Steppe into Europe too, save for Hungarian; all Viking conquests (rather than first settlements); all Germanic-speaking elites established after the fall of Rome in France, Iberia, Lombardy and North Africa. In every case, the elite’s language soon vanished. (..)

When and why conquests either do or do not bring about language replacement is clearest in cases where the same conquering entity spreads its language only to some areas, not others, as for instance in the Ottoman, Inca or Roman empires. Longer or shorter duration of control is sometimes suggested as potentially relevant, but in fact correlates rather poorly in these three examples. Again, more relevant seems to be whether conquest did or did not entail an incoming demographic component significant relative to the indigenous population.

As such, he in general speaks out in favour of language shift/expansion entailing a relevant demic, i.e. genetic, component, with one exception, however:

Crucially, human population prehistory has not been a series of uniquely two-way encounters and ‘language contests’ that always pitted a conquering elite against a conquered majority speaking just a single language. Where an incoming group, even if relatively small, comes to be dominant instead over a fragmented patchwork of many minor local tongues, in speaker numbers the elite’s language may rank as at least first among equals, i.e. as one among a multiplicity of small language populations, with no one major rival. New Guinea presents just such a patchwork of acute linguistic diversity, hinting that a similar scenario may have held more widely across neighbouring Island South-East Asia too, before the Austronesian expansion overwrote it there.

In such circumstances the incomers’ language does not face an uphill struggle against drift to fixation in favour of a single numerically overwhelming native language. Rather, against any other single language it has rough parity in demographic strength, allowing its primacy in other respects to promote language shift toward it. One key element is the incomers’ ability to establish a new coherent unit or network, of far greater territorial range than any predecessors, and/or with more intense interaction across it.

This leaves, for the disputed cases (Anatolian, Tocharian, Indo-Aryan, etc.), the question how linguistically fragmented the natives were when IE speakers arrived. As concerns Tocharian, the BA Tarim Basin was in all likelyhood linguistically diverse (Altaic, Tibetan, Sinitic, maybe Yennisean). LN/EBA Anatolia was certainly also linguistically diverse (Hurrian, Hattic, Semitic, possibly Sumerian), but local entities had considerable political and administrative strength, and corresponding resilience against linguistic overpowerment. The same should also apply to the Indus Valley.

A problem with Heggarty is that he is still fixated on the Fertile Crescent as origin of farming, and IE spreading as farming language from there. In his latest models, he has moved away from the Fertile Crescent’s NW periphery, i.e. E. Anatolia, to its eastern periphery, the Central Zagros. However, the recent Shinde paper shows that such model is also not feasible aDNA wise: Pre-Steppe MLBA IVC periphery populations lack any Anatolian ancesty – an ancestry already present in Zagros_EN.

There is, however, increasing evidence for an independent development of farming outside the Fertile Crescent in N. Iran. Points in case are

1.) Independent goat domestication in N. Iran/E. Caucasia, with haplotypes that differ from E. Anatolia, the Zagros and the Levante,

2.) N. Iran as independent center of barley domestication, again with a haplotype differing from N. Syrian and Levantine wild and domestic varieties,

3.) A specific N. Iranian/Central Asian Neolithic model (Sang-Chakmak/ Jeitun) that contrasts with the Anatolian/EEF model by a/o

a.) Preference of barley over wheat,

b.) Absence of domesticated pigs, and

c.) A focus on small ungulates (sheep/goat) rather than on bovids, which dominated in Anatolia and the European EN (including the Sursk Culture around the Dniepr Rapids, a possible Shulaveri-Shomu offspring, see e.g. Gronenborn’s famous maps on the spread of farming ).

Noteworthy in this context is also that N. Iranian “soft ware” (Kamarband/ Belt Cave) seems to considerably precede pottery making in the Levante and E. Anatolia (and also in W. Siberia).

There are still various gaps to fill archeologically and aDNA-wise. Nevertheless, the most plausible model I see at the moment (and in fact the only one that may be consolidated with all the aDNA evidence now available) is a PIE homeland around the Alborz Mountains in N. Iran, with early (Neolithic) spread across Central Asia and beyond (Hindukush), Eneolithic spread along the E. Caspian towards the Steppe (Pre-Caspian Culture->Yamnaya/Sredny Stog), and an EBA spread towards Anatolia as part of the Kura-Araxes expansion. The latter also reached the Central Zagros, resulting in cultural (and linguistic) contact with Sumerian.

It’s good to see someone speak up.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andronovo_culture:

“According to Hiebert, an expansion of the BMAC into Iran and the margin of the Indus Valley is “the best candidate for an archaeological correlate of the introduction of Indo-Iranian speakers to Iran and South Asia,” despite the absence of the characteristic timber graves of the steppe in the Near East, or south of the region between Kopet Dagh and Pamir-Karakorum. Mallory acknowledges the difficulties of making a case for expansions from Andronovo to northern India, and that attempts to link the Indo-Aryans to such sites as the Beshkent and Vakhsh cultures “only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central “Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans”. He has developed the Kulturkugel model that has the Indo-Iranians taking over Bactria-Margiana cultural traits but preserving their language and religion while moving into Iran and India. Fred Hiebert also agrees that an expansion of the BMAC into Iran and the margin of the Indus Valley is “the best candidate for an archaeological correlate of the introduction of Indo-Iranian speakers to Iran and South Asia.”

The basic idea of why Harvard’s model fails. It’s actually wrong on so many levels from the identification of Indo-Iranian to the lack of basic knowledge of the RV/Avesta and general Iranian history/ideology (Sassanid especially).

I do not think Indo-Aryan was from a BMAC migration to India, either. It’s a more complex process but imma wait for Atriðr.

From 2100 to 1500 bc Sintashta – Andronovo is supposed to have migrated from Eastern Europe to the edge of southwest asia and differentiated into Indo-aryan and Iranian and parted ways. Their descendents, the Scythians who inherit the steppe differentiate into East Iranian.

The only way for this to work is if the initial group is Indo-aryan and the latter group is Iranian. The other option is a choreographed symmetric split near the BMAC Iranian going southwest and Indiic going south east After that there’s a backwash of differentiated east Iranian back to Central Asia These are too many events to squeeze into a rather small space and time. Also in just 500 years, the Iranians consider the scythians as pesky barbarians and not as their cultural progenitors. This makes this scenario even more crowded and untenable.

The steppe-MLBA signal in India proper is 1200 BC at best.

What about the same signal in Iran? Surely there ought to be a steppe signal there t make the steppe theory work. But I don’t remember any discussion of that in Reich’s paper.

Frank: I’ll have a more careful look against what you’re saying vs Heggarty later, but I want to clarify that there is a common misconception about that Shinde’s paper suggests Anatolian ancestry in the samples we know about which have been previously labelled Zagros_N, at 10kya, relative to its absence in later people in South Asia.

This actually isn’t true if we carefully read the paper; compare the visual abstract against the date figure from Lazaridis 2016.

The samples Iran_N from Lazaridis 2016 have the same timing as the samples which Shinde 2019 labels “Iran herders”. “Iran herders” is labelled with 100% orange component. He doesn’t have new samples here. These are Zagros_N!

See: https://imgur.com/a/3MOGbpz

(within paper the Iranian groups are described as: “a pool of 8000 BCE early goat herders from Ganj Dareh in the Zagros Mountains, a pool of 6000 BCE farmers from Hajji Firuz in the Zagros Mountains, and a pool of 4000 BCE farmers from Tepe Hissar in Central Iran”)

He has not shown that the Zagros_N group have ancestry which South Asian groups did, but it’s something rather to do with the fact that these people archaeologically did not clearly practice cereal agriculture, while later Iranian groups that did, do have Anatolian ancestry. When he says “lack of Iranian farmer ancestry” in Rakhigarhi woman (whether true or not), this is because he’s re-labelled the Zagros Iran_N group as “Iranian herders” and the “Haji Firuz C” as “Iranian farmers”. The paper is IMO written in a somewhat obscure style that isn’t clear on this.

Above is only discussing whether Zagros_EN (assuming we’re talking about the 8000BCE samples here) had ancestry from Anatolia *relative* to South Asian groups.

In terms of whether they did in an absolute sense – remember that where we have Natufian dna at 13kya and now Anatolian dna at 15kya, these indicate that later farming groups in the Levant and Central Anatolia had ancestry from other Near Eastern populations which these older populations lack.

That seems quite likely to be the case again at the Zagros as well, though this is well beyond the scope of the linguistic questions here, and so semi-off topic.

“What about the same signal in Iran? Surely there ought to be a steppe signal there to make the steppe theory work. But I don’t remember any discussion of that in Reich’s paper.” — RB/postneo, Actually, i asked this question( presence of Steppe MLBA in iranian zoroastrians) to Vagheesh in a facebook group long time ago. He replied that they need an additional ancestry, IIRC from Seh Gabi Chalco.

@tim

Not just Zoroastrians but Iron Age samples from Iran analogous to swat valley. A time transect with onset.

I’m trying to put together a post looking strictly at the genetic data to try to give some insights into some of these questions. The whole “Iranian ancestry” is a bit confusing even when separated from the Caucasus one, so I’ll try to clarify some basic concepts that may be useful for further discussion.

Then I hope we’ll have some guest posts that will give a different perspective to what I can offer, especially with regards to textual data that I’m much less familiar with.

@Frank, not to sound boring, but you know the blog is open for you whenever you want to finish your last series or write anything else. But you’ll have to contact me because I can’t get in touch with you anymore on your former email address.

@All, if anyone is still doing G25 models, finally had a chance to getting around to using the new set of Global25 data to cook up a set of Indus_Periphery cline ‘zombie / simulations’: https://pastebin.com/tzTrZQAk

0AHG=point on InPe cline with 0% AASI, 100AHG = point on InPe cline with 100% AASI. Two different approaches in the file, but they basically converge on the same point.

Example plots: https://imgur.com/a/WgMiD25

0% ANI Basically something like both Turan+IranN with some differences… It’s difficult to know exactly where to draw 0% AASI, as it seems likely that IranN has some low level of ENA/AASI admixture that may confound attempts to find an endpoint. 100% AASI looks fairly distant from Onge. Again, I may have overshot this slightly, it’s hard to be sure.

(Edit: With the Global25, using a reprocessed PCA approach to look at the main directions of the South Asia cline (add to the plots in my post directly above), it looks like if a single population+any point on the extended Indus_Periphery cline must be chosen, Kangju (basically Sogdians?), for some reason look to have some qualitative superiority to Sintashta+Indus_Periphery, or Swat+Sintashta that expresses itself in some dimensions.

Not sure why, Kangju literally would be too late, but I would note that they were also a passing model in the paper’s qpAdm.)

Thanks @Matt.

is there a way to separate out the North indian iran like component from Indus_periphery and try to use it as source for admixture?

Is there a way to test if Iran_N fits better or IndianIranN?

Thanks Matt, I’ve already been making a few models for an upcoming post, but I’ll try to test with yours too an see what I get.

@A, I’m working on that now and will post soon about it.

@Alberto it would be useful to include post LBA, IA samples from Iran if they exist.

Thanks Alberto.

@ Matt – regarding the Shinde paper nomenclature. Figure 3 of the paper makes the labeling and dates of split quite clear.

@Alberto, that would be interesting to see, thanks.

I would agree with postneo that it might be interesting to see how post LBA IA samples from Iran behave – particularly they may have some impact in some populations in Pakistan, though less sure about India. May as well check it out though.

TKM_IA, Kangju with InPE cline may be workable for India, without a need to go to Reich lab’s InPeWest+Central_Steppe_MLBA model (or equally to exclude either; reality may be more complex than the simple 3-way model the paper presents in Fig4b).

I certainly think their models are somewhat flattening structure out along the southern end of the SA cline today as well, compared to what I see in G25 (e.g. there is a clear deviation of Irula, Paniya, Pulliyar, away from just being extensions of the same cline). Also wonder if the plot in Fig4B is not skewed by their choice to include some populations from Northern Pakistan who have geneflow with Tajik (TKM_IA) like populations, while excluding other populations from Southwestern Pakistan who have geneflow from Iran and Afghanistan. Their cline may not point to the same place if they hadn’t made that choice (which seems to be based, if on anything, possibly on circular reasoning)…

Study of modern Iranians

https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1008385