Horses

The domestication of the horse has been an event with important implications in human history, and as such it has drown the attention of archaeologist and historians for a long time, and more recently of ancient DNA studies. I’ll briefly recapitulate some of the latest findings mostly related to ancient DNA.

We know for a long time (in DNA era terms) that modern horses have a low diversity, specifically in their Y chromosome. This was supposed to mean that they all probably descended from a small group that was first domesticated, and that later only some wild mares from other places where incorporated into the domestic gene pool. However, last year’s Ancient genomic changes associated with domestication of the horse (Librado et al. 2017) revealed that ancient horses (mostly Scythian ones from the Iron Age) had a greater diversity than modern ones and that the modern low diversity is due to some bottleneck that happened somewhere between the Iron Age and the Middle Ages.

Earlier this year, another report was published (Ancient genomes revisit the ancestry of domestic and Przewalski’s horses, Gaunitz et al 2018) where it was revealed that Botai horses were the ancestors of modern Przewalski horses, but not to modern domestic ones.

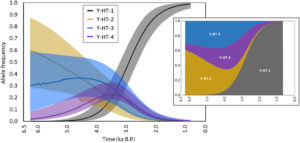

Finally, the Decline of genetic diversity in ancient domestic stallions in Europe (Wutke et al. 2018) analysed the Y chromosome of ancient horses finding 4 different haplotypes. The haplotype that is fixed in modern domestic horses (HT-1) was found to be very rare in early domestic horses, and first started to become prevalent in Asia during the Iron Age and later in Europe (either during the Roman period or the early Middle Age). Przewalski horses belong to HT-2, that seems to have been the most common lineage before domestication (probably being the main lineage in the steppe), while another 2 haplotypes (HT-3 and HT4) we found to be common in early domestic horses, but later disappeared.

So, as usual, we still don’t have a clear answer about where was the horse first domesticated. Generally speaking, I always considered that the western part of the steppe was the best candidate for the horse domestication, with Anatolia being a distant second option (other candidates being more marginal). I still think that the western steppe is the best bet, but somehow the fact that the Botai horses are not a genetic clade with early domestic ones seems a bit of a problem for it. For an animal as mobile as the horse, the steppe seems to be an easy corridor for continuous gene flow. I don’t know how parsimonious it is to think that horses of the western part of the steppe had diverged many thousands of years ago from the ones of the central part. Could be.

There was an old paper (Mashkour, M. 2003. In French) which looked at the osteological morphology of Botai, Przewaski, Dereivka and other ancient horses (wild and domestic) and found that neither the Botai horses or those from Ukraine or the Urals had the domestic morphology, which was better represented by other wild specimens from southern regions (Paleolithic horses from Portugal, Italy and Southern France, in addition to holocene ones from Iraq). While this is no substitute for ancient DNA, at least she was right so far about the Botai horses not being the origin of domestic ones. So let’s see what ancient DNA says about it in the next year or so.

[UPDATE: I just realised that a new paper appeared 2 weeks ago and I didn’t notice it.Late Quaternary horses in Eurasia in the face of climate and vegetation change, Leonardi et al 2018

Very interesting:

Iberia and the central Asian steppes harbored suitable environments for early horse domestication

We next investigated predictions of suitable climatic conditions around the time when horses were first domesticated. Between the proposed domestication centers (central Asia, eastern Anatolia, and Iberian Peninsula), the latter region remains very suitable for horses throughout the entire Holocene, while the Pontic-Caspian steppes show high values of p-Hor only up to 7 ka B.P. based on the European niche. The whole area surrounding Botai appears extremely suitable for Asian horses 5 ka B.P., in agreement with the archeological record supporting their domestication during the Eneolithic, but not for the European animals.

For some reason they consider both Iberia and Central Asia as the most likely places of domestication, without further commenting on eastern Anatolia. To me, if it wasn’t the Pontic-Caspian steppe, it seems that Anatolia would be the best bet. Might have to write a separate post about it if time allows.]

Wheeled vehicles

Like with domestic horses, the exact origin of wheeled vehicles is still unknown. Once they were invented, they spread fast throughout wide regions, independently of people and culture. Probably as with domestic horses, especially once these became really useful.

There is some debate about the correct terminology (wagons, carts, chariots,…) depending on the number of wheels, design, size, usage… so I will care more about the description than about the term used.

The earliest wagons date to mid 4th millennium BCE, and as mentioned above we don’t know their exact place of origin. Could be from somewhere around Central to SE Europe, to somewhere around Mesopotamia. They had 4 solid wheels and were pulled by oxen. While the appearance of wheeled transport is almost simultaneous in a large area from SC Asia to Europe, it appears a bit later in the steppe, coinciding with the early Yamnaya culture ca. 3100-3000 BCE. The Maikop culture is usually credited as the earliest one with burials containing a wagon.

[For a detailed discussion of the linguistic implications for the chronology of PIE you can read Anthony’s and Ringe’s The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives]

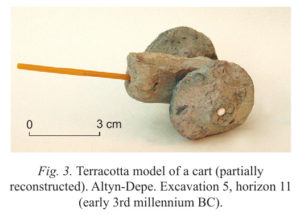

Two wheeled carts already appear in southern Centra Asia in the early 3rd mill. Draft animals were initially bulls, and later (2nd half of the 3rd mill.) also camels (THE EARLIEST WHEELED TRANSPORT IN SOUTHWESTERN CENTRAL ASIA: NEW FINDS FROM ALTYN-DEPE, Kirtcho 2009).

Meanwhile, in the Near East there was (long?) tradition of using equids either for work or for ritualistic purposes (EQUID BURIALS IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXTS IN THE AMORITE, HURRIAN AND HYKSOS CULTURAL INTERCOURSE, Silver 2014):

A tumulus grave SMQ 49 containing human remains, grave goods and an equid (Phase 3) has been recently found from As-Sabiya in Kuwait on the Arabian Peninsula. According to the author, the burial customs and associated grave offerings allow the dating of the tomb to the Late Neolithic–Al-Ubaid period, which would mean the date as early as the 6th–5th millennium BC. The neighbouring site has a strong Ubaid presence, and imports from Mesopotamia are abundant. If the dating is correct, as it seems with particular stone weapons and bone tools, this equid burial would be the oldest ritual burial of an equid known so far from the Near East. The equid was tentatively identified as an onager belonging to undomesticated equidae. (Makowski 2013). This earliest equid burial seems to be connected with Mesopotamia through the Al-Ubaid culture, the predecessor of the Sumerian Uruk culture.

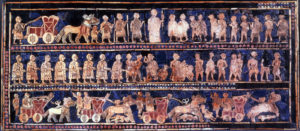

In the Mesopotamian finds chariot burials including equids have been found in Kish, Ur and Abu Salabikh from Early Bronze Age contexts. In Kish, Chariot Burial II contained four-wheeled chariots and four equids buried on top of them. The connection of the equids with the chariots has been disputed in the case. It is apparent that there was another chariot burial with three two-wheeled chariots that contained equids as well as Chariot Burial III. In Chariot Burial II, a mixed combination of equids, including horses (equus caballus) and asses (equus asinus and equus hemionus) were identified. Interestingly, the tombs are vaulted brick tombs which date from the Sumerian Early Dynastic period of the Early Bronze Age (Zarins 1986: 169–171). Abu Salabikh, an ancient Sumerian and Semitic site, also provides equid burials associated with humans dating to the Early Dynastic period. More evidence of equid burials including asses that are associated with humans have come from the Hamrin Basin in Mesopotamia (Zarins 1986: 171–175). The chariots discovered from the Sumerian Royal graves of Ur (dated to the Early Dynastic period) were either drawn by oxen or asses (Woolley 1946: 20). Clearer evidence of equids in Sumerian Ur come from the Ur III period graves, like from the grave of Šulgi and Amarsin dating from ca. 2100 BC. Animals were also sacrificed at the entrance to a tomb PG 1054 in Ur. (Woolley 1931: 343–345 and Woolley 1941: 40-41 apud Zarins 1986).

Also interesting in this respect is Burial customs at Tell Arbid (Syria) in the Middle Bronze Age. Cultural interrelationswith the Nile Delta and the Levant (Wygnańska 2008).

Wagons/carts (or whatever name one prefers), were driven into war using equids (onagers or asses) as draft animals, though these were still using 4 solid wheels and where probably not directly used in the battlefield:

An important set of innovations then came from the steppe, specifically from the Sintashta culture. Quoting D. Anthony (The horse, the wheel and language):

Eight radiocarbon dates have been obtained from five Sintashta-culture graves containing the impressions of spoked wheels, including three at Sintashta (SM cemetery, gr. 5, 19, 28), one at Krivoe Ozero (k. 9, gr. 1), and one at Kammeny Ambar 5 (k. 2, gr. 8). Three of these (3760 ± 120 BP, 3740 ± 50 BP, and 3700 ± 60 BP), with probability distributions that fall predominantly before 2000 BCE, suggest that the earliest chariots probably appeared in the steppes before 2000 BCE (table 15.1). Disk-shaped cheekpieces, usually interpreted as specialized chariot gear, also occur in steppe graves of the Sintashta and Potapovka types dated by radiocarbon before 2000 BCE. In contrast, in the Near East the oldest images of true chariots—vehicles with two spoked wheels, pulled by horses rather than asses or onagers, controlled with bits rather than lip- or nose-rings, and guided by a standing warrior, not a seated driver—first appeared about 1800 BCE, on Old Syrian seals. The oldest images in Near Eastern art of vehicles with two spoked wheels appeared on seals from Karum Kanesh II, dated about 1900 BCE, but the equids were of an uncertain type (possibly native asses or onagers) and they were controlled by nose-rings (see figure 15.15). Excavations at Tell Brak in northern Syria recovered 102 cart models and 191 equid figurines from the parts of this ancient walled caravan city dated to the late Akkadian and Ur III periods, 2350–2000 BCE by the standard or “middle” chronology. None of the equid figurines was clearly a horse. Two-wheeled carts were common among the vehicle models, but they had built-in seats and solid wheels. No chariot models were found. Chariots were unknown here as they were elsewhere in the Near East before about 1800 BCE.

So the Sintashta people seem to have been the inventors of spoked wheels, which made the carts much lighter and together with using a real horse to pull it, much faster and useful in battle. These innovations didn’t take long to spread either, as we already have a depiction of spoked wheels in the Near East around 1900 BCE and another with the full package (spoked wheel, horse, bit) around 1800 BCE. However, Mesopotamian artisans had more resources and managed to make some improvements over the steppe originals (again, from Anthony):

When horse-drawn chariots appeared in the Near East they quickly came to dominate inter-urban battles as swift platforms for archers, perhaps a Near Eastern innovation. Their wheels also were made differently, with just four or six spokes, apparently another improvement on the steppe design.

Mycenaean chariots appear around the 16th century BCE. They used 4 spoke wheels:

Like the rich burial tradition (and many other cultural and technological innovations), they must have arrived from the Near East. We’re still waiting for more Mycenaean ancient DNA, especially from early elite burials. The shaft graves (brief description of the contents , some pictures of their goods) might be able to provide some good insights, so let’s hope it’s not too long before we get to see those results.

Another interesting paper is by Ludwig et al (Coat Color Variation at the Beginning of Horse Domestication) – using coat colour SNP variation suggests domestication began c 3000 BC, in line with the data from Botai (c. 3500 BC).

As Robert Drews (a military archaeologist) sketches out neatly, the use of horse evolved from food to traction animal then to hauling chariots then horseback warfare

Is the hypothesis that Suvorovo raiders used horses to arrive

and get off in a surprise attack possible ?

Perhaps. But it goes against several lines of evidence and has little positive evidence in return. In fact, in laying the collapse of Chalcolithic societies to steppe raiders in 4200 BC, it tends to miss a large part of the big picture as to the events surrounding 4000 BC by making a mountain out of a molehill .

A lingering question for me is what role of B.B. sites like Csepel which are thought to have been horse trading centres. It’s time of 2500 BC fits within the domesticate time frame.

@Robert

Thanks, I forgot to mention that other study in the post.

I agree that the Suvorovo intruders riding horses seems more in the realm of legend than reality. Even more to be the cause the Copper Age collapse in the Balkans.

The Central Asian model not working for the early European domestic horses, and the low probability of Iberia as the main place of domestication leaves us with some good questions about other possible places.

Anatolian horse results should not be too far away by now, so let’s see what they show.

Off topic, but since many readers have a special interest in South Asian genetics, Chad Rohlfsen has began a post about it here:

https://populationgenomics.blog/2018/08/08/another-look-at-south-asian/

Some of you might want to take the chance to comment or ask about some other tests there.

Yes I’m sure we will find out soon where horse domestication first occurred – it might be surprising for most but few people 🙂

By the way, a minor but important point, you suggested that the earliest wagons in a steppe context appear with early yamnaya. If i recall correctly, the wagon first appears with a late steppe -Eneolithic horizon called the “Zhivotilovka-Volchansk horizon” c 3300-3000 BC. It is characterised by Maikop and CT ceramics in burials, and a burial posturing not encountered before on the steppe, nor continuing after. It gives the impression of a few people moving through, leaving some lasting cultural elements, but themselves disappearing (?)

If I were to speculate, the Yamnaya female “outlier” might have the genetic clues of this population, and links to Majkop. However some more contextual analysis of further samples would help clarify. I’m sure someone somewhere has their hand on it

Alberto, the link to the pictures of shaft graves is incomplete. I think I’ve found the page you meant to link to https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/mediterraneanbronzeage/files/3759747.pdf

@ak2014b

Thanks, fixed now.

I’m not up to date on the chariot evidence at Sintashta. I read the news originally reported around the mid 1990s of David Anthony’s finds of what were possibly chariots.

News reports mentioned that the assigned dates were contested. There were no actual chariot remains, only the stains made by wheels and some superstructure. Archaeologists dated the grave goods at the site to 1600 BC. Anthony had the horse bones at the site dated, which were found to be from a little before 2000 BC. Anthony went with the date of the horse bones for the chariots a.o.t. using the date of grave goods. (http://discovermagazine.com/1995/apr/chariotracersoft500) Anthony’s interviews of the time mentioned he felt that this meant chariots may have been invented in the steppes. But it was not fully resolved for others. For instance, if the grave goods actually belonged with the buried vehicle (other archaeologists did write that the ostensible chariots of Sintashta were purely grave goods and never put to actual use), and if the horses were from an earlier layer, as turned out to be the case in some other key finds by Anthony, then this once more puts question marks over the geographic origins for true chariots and over the earliest dates for their appearance in the steppe.

At the time, it was moreover not unanimous that the wheel imprints necessarily belonged to chariots. Like the argument presented at http://nytimes.com/1994/02/22/science/remaking-the-wheel-evolution-of-the-chariot.html, ‘Mary Littauer, an independent archeologist and co-author of “Wheeled Vehicles and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East” (Brill, 1979), was not ready to concede the point. “It’s still debatable,” she said. “A spoked wheel is not necessarily a chariot, only a light cart on the way to becoming chariots.”‘

I am likely to have missed a lot of the subsequent developments in the state of the evidence since the mid 1990s, and have tried to find them but have not had any success. Does anyone here know if there’s been further evidence from Sintashta since then that has been able to resolve these uncertainties and which have at last clearly established that the Sintashta structures are in fact of a chariot, a true chariot moreover, and with indisputable dates now provided? (Evidence as clear, tangible and date-able as what we have for various carts to chariots of the Middle-East, for instance.)

Alberto, do you further know of any photos of the imprints of the wheels that show off the spokes of the Sintashta chariots? I’ve seen drawings and reconstructions, and some foggy photos, but have long wanted to see some photos showing the spokes clearly.

> Yes I’m sure we will find out soon where horse domestication first occurred – it might be surprising for most but few people

Besides the western steppe, Iberia and Alberto’s additional suggestion of Anatolia, is there a case to be made for Armenia or the southern Caucasus for horse domestication? Anthony mentioned that the same indicators implying possible horse domestication (possible bit wear) that were found in Botai was found earlier in Armenia by other archaeologists.

@ Ak2014b

Yes I recall the shifting dates. I’ll try look st it further. As you mention, it wouldn’t be the first time a date has been incorrect, and sometimes “facts” are just echoed from writer to writer.

About horse domestication, I’m not privy to the results (& wouldn’t say so if I did). But I’m sure they’ll make sense in the big picture of pastoralist development.

Thanks! Anything you find could go a long way to answering my questions.

> About horse domestication, I’m not privy to the results (& wouldn’t say so if I did). But I’m sure they’ll make sense in the big picture of pastoralist development.

Yes, I understand. I look forward to any publications that deal with this. Hopefully it won’t be long. Fortunately, FrankN’s 2nd guest post has a more definite date of around next week, so there’s other interesting revelations to look forward to in the immediate future.

If you get a chance, Rob, could you look at my questions for you at https://adnaera.com/2018/07/29/some-interesting-fresh-adna-from-central-europe/#comment-159? It’s understandable if you’re unable to respond with answers if in doing so you might have to reveal something that you’re not free to disclose.

@ak2014b

When Nick Patterson wrote at Eurogenes that the only reason why they didn’t publish any sample from India was because they just didn’t have them, and not for any political agendas, he was telling the truth. You’ve already read reports about the difficulty to get DNA from those Rakhigarhi samples, with apparently only one being really usable after years of trying (and that’s the only reason for the delay).

So I think that a boutade during a heated debate echoing some rumours that were circulating should be taken just as that. There’s no successfully sequenced Neolithic DNA from India so far (thought it might be on the way).

Regarding the Sintashta questions, I think that there has not been further data corroborating it in an unambiguous way (though I might have missed it), but with the evidence available it does seem reasonable to accept it as the most likely scenario for now. In any case, it doesn’t have much historical relevance, since like wagons and solid wheels more than a thousand years before, they spread faster than the people who invented them. By the time Sintashta/Andronovo people might have started to go south, the people from the south already had better chariots, so that was not an advantage for the non-existent conquering that some people fantasize about.

I can corroborate that extracting DNA from hot climates- as everyone knows- is extremely challenging. We’re talking about 1 in 50 success rates from what I’ve heard of people working in Greek and Anatolian data , so 1 of ~ 100 from India, whilst painful, seems in line with expected challenges.

Most academics don’t have the personal passion in such questions as “IE origins” one sees in the blogosphere does, but merely take it on as one of many other academic & research projects (teaching & other more mundane stuff such as applying for grants,etc) even if they align with certain perspectives.

If the data is analysed systematically and through various perspectives, that’s all we can ask for.

@ AK2014b

Trying to think back, I think I made a rather bold suggestion that there might be R1a of sort in Neolithic ? If so, it was based on whatever current data existed (eg Siberian Neolithic R1a in Moussa et al – which was not reproduced in recent papers; R2 in Iran, and “archaeological deduction”).

As things stand, Z93 expanded from EE, as most people would agree. But some of us were correct in pointing out some possible more ancient EHG – like strata in SCA which inflated previous predictions (academics and bloggers alike); and that the crashing of “Bronze Age badassess” doesn’t seem to have occurred. As Alberto pointed out, have a look at Chads blog for the current state, because he’s unbiased and has a developed understanding of collateral evidence.

So we have some steppe MBA admixture in South Asia by the early Iron Age, and perhaps more as time goes by (not unexpectedly given the known movements from Central Asia). What this means overall remains open.

Thanks both.

I was interested in that Neolithic R1a statement because there’s also R1a in modern Southeast Asia, as well as some potential paternal connections between the Aeta and South Asia. I tentatively reasoned that if R1a turned out to have been widespread over Eurasia so early on, with additional presence in South Asia, then maybe it may have been there in Southeast Asia early too. The subsequent Southeast Asia aDNA papers reduced the likelihood of that, though the relatively small number of samples still allowed for some little leeway. But until those papers appeared, I’d certainly been wondering in which direction and time this (as well as some other ancestry) had travelled between South and Southeast Asia, since mtDNA M may have entered from Southeast Asia into South Asia quite early on. However, as it’s now been reiterated that R1a is firmly established by all the aDNA we now have as being from Eastern Europe and only arrived in South Asia relatively recently, that question is laid to rest.

I should say I’d not been following much of the aDNA discussions after the Southeast Asian papers came out, which kept me satisfied for some time. I have yet to properly catch up on many subsequent papers including the Central Asia one.

I wasn’t aware of Nick Patterson having said that. Disappointing. But if they did get one working sample out of ~100 now, that’s something. And I see a paper about it is indeed rumoured at anthrogenica as coming out soonish, though I’m not sure any more what soon means in these cases.

It seems they only managed to ultimately get 1 proper sample out of 148 samples, as per anthrogenica. Back to feeling disappointed again. Didn’t the first Southeast Asia paper do better? And the second paper (the Harvard one) got fewer than that, but still nearly 20 Southeast Asian samples out of over 100. Is the climate comparable or worse for aDNA research purposes in that part of South Asia than it is in Southeast Asia?

There’s mention at anthrogenica (https://anthrogenica.com/showthread.php?8066-DISCUSSION-THREAD-FOR-quot-Genetic-Genealogy-and-Ancient-DNA-in-the-News-quot/page159) of a recent news report hinting at the kind of results to expect. It seems the results may be as many had anticipated, at least based on that solitary sample. It would be better to draw conclusions from more samples, but there’s nothing to be done.

An odd quirk is that that news report was linked from Anthrogenica on the 8th of August, but the date for the report is from the future: 13 August 2018 (while today it’s still the 10th or 11th depending on where we all live). Though probably just an error, it’s tempting to think that it’s hinting at the day that first IVC aDNA paper itself will be published, with the news report about it originally meant to come out then too or on the eve thereof, but then maybe the news report ended up going to print earlier anyway. It would be great to hear about the results as soon as all that, though it could easily end up dragging on for months again.

I wonder when we’ll see more Mycenaean Greek and Hittite aDNA. The IE question seems to grow closer and then again more distant to being solved.

@Alberto,

If you’re also unable to find definitive evidence, then I’m no longer convinced now about chariots of any kind in Sintashta. Archaeologists, including Anthony himself, have had over 3 decades now to find more conclusive evidence. The fact that that it hasn’t been found, and that in the meantime what he originally described as his “gut feeling” about Sintashta originating chariots has merely morphed (without the backing of additional support since) into blogs and fora repeating his feeling as a certainty, may indicate that no more work is being done or that there may be no further evidence to back up the claim.

Unambiguous chariots and true chariots have been found elsewhere. Until the archaeological finds at Sintashta, the Middle-East was for this reason considered to have been the origin of the chariot and for various developmental stages of it, including of the true chariot as per my understanding. For instance, the earlier mentioned 1994 news report at https://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/22/science/remaking-the-wheel-evolution-of-the-chariot.html says about the Sintashta finds that “The discovery could also lead to some revision in the history of the wheel, the quintessential invention, and shake the confidence of scholars in their assumption that the chariot, like so many other cultural and mechanical innovations, had its origin among the more advanced urban societies of the ancient Middle East.”

However, if there’s still the reasonable possibility that the chariots in Sintashta are not so early after all (or actually chariots at all), then the previous dates for earliest instances of chariots being in the Middle East ought to take precedence again, as that region had what were unambiguously chariots based on clearly date-able evidence. The Middle Eastern chariot evidence dates to 200 years past the higher end date that Anthony settled on for the finds at Sintashta (http://discovermagazine.com/1995/apr/chariotracersoft500 again), and this is what finally gave Sintashta the edge in the quest for determining where the vehicle originated. But with that as a question mark, the Middle Eastern dates, despite being 200 years later, at least offer certain evidence of definite chariots at that definite time.

The Middle East further demonstrates, starting at far earlier times, development stages from early wagons to get to chariots. And we know with certainty that they were used as chariots. In contrast, Sintashta is a culture that started around its presumed fully developed true chariot’s assigned date of around 2000 bc. Sintashta chariots, or carts as they may have been, have further not been shown to have been put to any actual use at all, only as grave goods. (Notwithstanding arguments by Anthony or anyone else to make a case for their use.)

There are also follow-on effects and assumptions that become open-ended again. For instance, a main reason for Sintashta as the source of Indo-Iranian was that it had true chariots. If it possibly didn’t have true or other chariots after all, then that weakens the dependent argument that it must have been Indo-Iranian. For example, there are other steppe MLBA cultures rich in R1aZ93 up for consideration as Indo-Iranian homeland again. Though if they didn’t have chariots either, and if chariots have to remain closely tied to Indo-Iranian, then maybe this is a larger problem? Perhaps this is even connected to your pointing out the surprising paucity of R1a in the aDNA from Swat in South or South Central Asia in a recent paper, and its late presence there. I’m not comfortable with ruling anything out about this yet. I merely wish to observe that if Sintashta has not provided definite evidence of early chariots, then the runner up for earliest should become the primary contender once more. Anything less further does an injustice to Middle Eastern history.

It’s therefore frustrating that so many have been made to labour under the assumption (as I had) that Sintashta originated the true chariot or had chariots at all, if this indeed remains ultimately an assumption up to the present. I think those who continue to conclude so ought to be corrected from now on, so that it doesn’t continue to proliferate and so they can avoid mistakenly building further assumptions or arguments on shaky foundations. As a consequence, I’m no longer as closed to Anatolia or the Caucasus or FrankN’s suggestion of NW Iran as valid alternatives for the PIE or LPIE homelands, now that several lines of evidence for a steppe homeland that I once thought were certain have proven less so.

@ak2014b

Yes, you have a point there. As Robert also mentioned above, it’s quite normal to see that someone’s hypothesis turns into an accepted fact without much scrutiny. It is frequent in books to read things like that Afanasievo introduced metal working to China (or horses, or wheeled vehicles) for which the evidence is completely absent (basically the same that can be said about linking Afanasievo to Tocharian language). Many things about the steppe were based in very old non-C14 dated reports that had never been seen or verified by western scholars and that were in dire need of revision.

Besides, I also agree that David Anthony has been quite vocal using strong arguments to support as facts things that are just hypotheses. The kind of arguing that can be seen in the paper linked in the post about the importance of wheeled vehicles for the chronology of PIE (though I find the general argument acceptable, his arguing is far too radical in his assumptions about “impossibilities” and our ability to infer with any certainty things about languages spoken over 5000 years ago for which we have no direct evidence (or even close to them). A more nuanced argumentation would be welcome, but then it would not be so effective in turning it into an accepted “fact”.

So yes, these things do need some further debate, and experts should be more critical when examining certain hypotheses instead of just accepting them as proven facts based on some big words.

On a related note, I forgot to mention the recent news about a chariot unearthed recently in India (but again, these are early news that will need some time to be verified, understood and put in the right context):

https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/asi-excavated-sanauli-chariots-have-potential-to-challenge-aryan-invasion-theory/312415

One can always refer to the sober analysis Karl Lamberg-Karlovsky

https://books.google.se/books?id=fHYnGde4BS4C&pg=PA156&lpg=PA156&dq=carbon+date+sintashta+chariots&source=bl&ots=qEVgQDhAP1&sig=nQzXu-_3GUDZ1tKuRlMRDrJu5mA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj8p966zOTcAhUBzmEKHf4sAt0Q6AEwCnoECAAQAQ#v=onepage&q=carbon%20date%20sintashta%20chariots&f=true

Thanks and thanks.

The page (156) that Rob has pointed out notably contains “The Sintashta chariots are by no means the earliest ones known. There are several sealing impressions depicting a chariot and driver in a Mesopotamian Early Dynastic III glyptic, c 2500 BC (Littauer and Crouwel 1979; Green 1993: 60).”

Mary Littauer, the first author cited, is the same archaeologist who was interviewed and found the chariot nature of Anthony’s Sintashta finds to be debatable. That would make the 2500 BC Middle East vehicle mentioned in Littauer and Crouwel 1979 an indisputable chariot, considering how exacting Littauer is about the definition.

Such a very early Middle Eastern chariot deserves to become better known, with credit rightfully restored.

> On a related note, I forgot to mention the recent news about a chariot unearthed recently in India

I was made aware that South Asia possessed wagons and carts (and possible chariots, from miniature figurine forms) mainly from a link at anthrogenica to a paper by Kenoyer, on the kind of ancient wheeled vehicles developed in South Asia.

IVC’s copper-based metallurgy is roughly contemporaneous with Iranian settlements, starting around 6000 or 5000 bc. The wheels used in the IVC vehicles were solid, not spoked, which matches up with the report, “The wheels were found solid in nature, without any spokes, Dr Manjul says.” Furthermore, Iran attests to chariots with crossbar wheels by 2350 bc. So for South Asia to have had copper chariots in the reported period of 2000-1800 bc isn’t entirely unexpected.

However, for Indian chariots to be relevant to any discussion of Indo-Iranian, it’s expected they be true chariots: harnessed to horses, having spoked wheels and matching those other particulars defined in your quotation from Anthony. Sintashta was presented as fitting the bill, though now it seems it’s not guaranteed to fit the basics.

Kenoyer did bring up mention of spoked wheels in regards to the IVC, as well as new accounts of IVC spoked wheel data that he hadn’t personally verified, but he noted that the topic itself was controversial for being considered associated with IE (and therefore considered mutually exclusive with IVC). I’ve not kept abreast of further developments surrounding this, however.

And in looking for further information, there’s still no actual knowledge about the kind of draft animals involved in the India chariot finds, though the researchers don’t rule out horses (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-06/07/c_137237324.htm)

‘On animals used to draw the chariots, Manjul said, “It could be a bull or a horse, but having said that the preliminary understanding points to the horse.”‘

And since the wheels were further described as solid and therefore without spokes, they’re not true chariots. Despite that, these new finds in India are very interesting in their own right, including the buried royalty with their copper weapons. This shows the native cultures encompassed warriors among its population, and that South Asian metallurgy had also been used for warfare. The other interesting feature is that these Indian chariots, currently estimated at 2000-1800 bc, are in copper. In contrast, Sintashta’s ones are from either 2000 or otherwise 1600 bc and were to have been made of wood as explanation for the absence of any actual chariot remains and only imprints surviving. This contrast seems to confirm what you said, that Steppe MLBA could not have invaded to find a helpless population at all, but one armed with metal chariots besides weapons.

Hopefully we’ll get to see some interesting aDNA from the presumed royal remains associated with the buried chariots.

There’s mention of a new paper “Horses may have been ridden in battle as early as the Bronze Age (Chechushkov et al. 2018)” at http://eurogenes.blogspot.com/2018/08/horses-may-have-been-ridden-in-battle.html

An excerpt states “We investigated changes in function over time through the use of experimental replicas used in bridling horses. This experimental work supports the hypothesis that these objects served to bridle harnessed (shield-like) or ridden (plate-formed and rod-shaped) horses. Moreover, comparison of use wear on the ancient artifacts with the replicas provides insight into how long the artifacts were used before they were deposited in the funeral contexts or discarded. These observations support that the Sintashta chariots dating back to ca. 2100 BC were ridden and suggest the end of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1500–1200 BC) as the earliest possible date for horseback riding in warfare.”

It’s an example of research also descending into ‘building further assumptions on shaky foundations’ of my earlier complaint.

The date and very nature of the Sintashta vehicles as chariots are contested. Selectively reiterating Anthony’s date for the chariots has made Sintashta into a myth that’s built up, rather than uncovering the historical reality of Sintashta as far as this can be uncovered. Experiments using replicas to argue that Sintashta vehicles were put to use do not amount to actual evidence, when archaeology has not been able to actually show that they were ever more than merely grave goods, such as by the attestation of wheel tracks.

For contrast, on a genetics forum, there were people demanding evidence that the early attestation of toy wagons and carts in the form of miniatures in South Asia translated to real life use. Evidence was demanded citing that Aztecs too had toys with wheels and that it didn’t follow that these were put to use. The expectation was therefore that wheeled vehicles remained as toys in South Asia as well. In response, Kenoyer’s paper was cited for mentioning the wheel track marks of a wagon, and finally laid that to rest. However, similar to assumptions about Afanasievo, for Sintashta too, no one asks for archaeological evidence like track marks. Experiments with replicas seem to suffice to settle the matter. Using methods to merely infer conclusions about the past may not have been acceptable for wheeled vehicles in South Asia had there been no wheel tracks.

It has turned out that the Middle East has very early chariots compared to Sintashta (2500 bc vs 2000/1600 bc), but there’s this general disinterest to consider anything non steppe as a source of innovation for things the steppe is “competing” with. The resulting discussions seem to take place in isolation from the rest of world history, as if the rest doesn’t exist. It’s detrimental enough for non-experts to indulge in this, but it becomes worse when the behaviour extends to the realm of research.

Another example of this is the general sounding claim in the new Chechushkov et al 2018 paper that their replica based experimental results “suggest the end of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1500–1200 BC) as the earliest possible date for horseback riding in warfare.” Yet at http://kavehfarrokh.com/iranica/militaria/military-history-and-armies-of-scythians-sarmatians-and-achaemenids/image-of-a-jiroft-horseman-with-short-lance/ is tangible evidence, in the form of a photo of a sculpture depicting a rider bearing a lance, sitting astride a bridled horse. (It actually looks like he has a helmet of sorts on, further suggesting the context of warfare.) The sculpture is from the Jiroft culture, in Iran. When I search for “Jiroft”, google comes back with “Jiroft culture: c. 3100 – c. 2200”. This is far better evidence of early horseback riding in warfare than experiments with replicas. It’s also far earlier than Chechushkov et al 2018’s timeframe of 1500-1200 bc, yet the evidence from Jiroft is presumably ignored or perhaps deemed insufficient. The result is that the world at large remains ignorant of actual world history. If the same figurine had been found in a steppe culture, especially at that early date, the treatment would be totally different.

Kuz’mina and several other specialists have repeatedly stressed that archaeological data has so far not been able to provide evidence for mounted warriors in the steppe until the end of the 2nd millennium bc. The recourse to results from experimental replicas to now argue otherwise, feels like an attempt to bypass the lack of archaeological support. I’m not sure why researchers so invested in the subject don’t just accept it or continue to look for more actual evidence in the steppe. None of it however explains why earlier evidence from other places continues to be ignored.

@ak2014b

A problem that I mentioned in the post is the terminology used. Is it a requirement for a chariot to have spoked wheels instead of solid ones? Is it a requirement that it’s pulled by true horses and not some other equids? And is it necessary that the driver is standing and not sitting? And should they use bits and cheekpieces or are those unnecessary?

What apparently was invented by the Sintashta people was the spoked wheel and the use of true horses with bits and cheekpieces.

The “sealing impressions depicting a chariot and driver in a Mesopotamian Early Dynastic III glyptic, c 2500 BC” might not qualify. For example, in “Excavations at Abu Salabikh, 1978-79” by J.N. Postgate (page 104) there are some descriptions mentioning “Head of horse (?) – ridge for mane, ears and pierced nostrils“. Also: “Figure seated in two-wheeled chariot drawn by equid(s), which trample on a recumbent enemy. Behind chariot, jar or outsize dagger and a skirted figure.”

Regarding the importance of spoked wheels for Indo Iranians, this should be understood as a symbolic thing, and not literally as wheels made with spokes and used in real vehicles. The symbolism described in the Rigveda regarding the wheel (chakra) with specific number of spokes depending on what it symbolises is well represented during the Chalcolithic in amulets or even terracotta wheels (for vehicles) that is unclear if they were made with spokes (unlikely, since they’re made solid in terracotta) or just decorated with spokes for its symbolic meaning. This kind of symbolism is important and mostly ignored when interpreting the Rigveda as a proof of a steppe origin of the Aryans.

A good article and discussion can be found at indologist Giacomo Benedetti’s blog here:

http://new-indology.blogspot.com/2016/12/the-wheel-from-mehrgarh-to-vedas-and.html

Thank you, I’ll have a read. I did not mean to sound dismissive of the India finds. I accept it can be some kind of chariot, but meant to point out that it fails to meet the specifications for true chariots because of the type of wheels.

> What apparently was invented by the Sintashta people was the spoked wheel and the use of true horses with bits and cheekpieces.

Yet even so, the problems pointed out earlier would remain. If the horse bones were of 2000 bc and the grave goods at the burial site were from 1600 bc, and if the ostensible chariot still could be from either period, then if the vehicle was in fact from 1600 bc, they can’t demonstrate its connection to the horses. Anthony would have had to conclude the vehicle was of the same era as the horses in order to make his argument that this was the place true chariots first originated, thereby dislodging the true chariots found 200 years later in the Middle East from primary consideration.

All others are expected to be rigorous with their evidence, those making a case for the steppe ought to be held to the same standards. Until there is certainty regarding the dates, the Sintashta vehicles if true chariots cannot be mentioned as the earliest without constant qualification.

Moreover, Littauer’s argument (above) was that the evidence from Sintashta was not sufficient to conclude it was necessarily a chariot generally. That would consequently rule out that there was sufficient evidence to satisfy the more restrictive requirements for the true chariot.

But Littauer and Crouwel gave more complete consideration to Anthony and others’ claims when they later returned to the very subject matter of true chariots in a paper responding to Anthony’s early date for the Sintashta finds as war chariots. It’s a paper which incidentally reproduces the kind of photos from Sintashta that I was earlier searching for.

In The origin of the true chariot (Littauer & Crouwel 1996) the two authors take the reconstructions of the Sintashta chariots and Anthony’s date in stride (2000 bc-1800 bc as it turns out, a.o.t. 2000 bc), as also working by Anthony’s arguments that horses would have been ridden early in the steppes. They clearly express reservations about the reconstructions, but by taking these seriously the authors point out the Sintashta vehicle is flawed mechanically. When they take only the actual archaeological remains into consideration, the authors find the Sintashta two wheeled vehicles could not have served for warfare or racing purposes. (The 2 purposes Indo-Europeans are to have used them for.)

They still come to the conclusion that both the chariot and true chariot’s origins were in the Middle East rather, further pointing out that the continuous development and refinement of wheeled vehicles from 4 to 2 wheels to chariots and true chariots is demonstrable there. In contrast, “no early tradition of fast transport by two-wheeler existed on the steppe”, referring also to Izbitser’s work (1993) on the earlier steppe Pit-Grave culture’s 4 wheeled vehicles, of which they remark “What also seems to emerge from Dr Izbitser’s work is that many of the four-wheeled vehicles buried with seated passengers would have been more suitable for processions and for burial rites than for workaday use. These must have been ceremonial, status-conferring vehicles.”

The authors find the lighter spoked wheel of the chariot too was to have logically been developed in the Near East (so despite Anthony’s earlier date): “Does it not seem more likely that the horse’s introduction to draught in the Near East stimulated the local wheelwrights to invent a lighter wheel for the already long-existing two-wheelers than that people without a history of two-wheeled vehicles and with an already superior personal conveyance – the mounted horse – should find reason suddenly to invent such a vehicle in its entirety?” For comparison, in the Near East evidence “The scenarios are one of improvement and development out of an established and very useful artefact”. Littauer and Crouwel state with reason “We should like to suggest that it was the prestige value of the Near Eastern two-wheelers that inspired imitations on the steppes”.

The final section of Littauer & Crouwel 1996 is as instructive as the whole paper, which deserves as wide an audience as Anthony’s “The Horse” has obtained,

“A Near Eastern and a steppe origin has been previously argued by the authors (Littauer & Crouwel l979: 68-71) and by Piggott (1983: 1034) respectively. Piggott later adopted a more cautious view (1992: 48-9; cf. also Moorey 1986). The idea of the war chariot originating on the steppes has recently been revived, chiefly on the basis of the calibrated radiocarbon dates from Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero (Anthony & Vinogradov 1995: 4041).

‘ Proto-chariots’

Let us consider what is actually known of the Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero vehicles. At Sintashta, there remained only the imprints of the lower parts of the wheels in their slots in the floor of the burial chamber (FIGURE 1); Krivoe Ozero also preserved imprints of parts of the axle and naves. At Sintashta, the wheel tracks and their position relative to the walls of the tomb chamber limited the dimensions of the naves, hence the stability of the vehicle. Ancient naves were symmetrical, the part outside the spokes of equal length to that inside. Allowing enough room for the end of the axle arm and linch pin on the outer side of the nave and for a short spacer on the inner side of the nave end to keep it from rubbing on the body of the vehicle, we are left with no more than 20 cm for the entire length of the nave. The shortest ancient nave of which we know on a two-wheeler is 34 cm in length, and the great majority are 40-45 cm (Littauer & Crouwel 1985: 76, 91). The long naves of ancient two-wheelers were required by the material used: wooden naves revolving on wooden axles cannot fit tightly, as recent metal ones do. The short, hence loosely fitting nave will have a tendency to wobble, and it was in order to reduce this that the nave was lengthened. A wobbling nave will soon damage all elements of the wheel and put all parts of the vehicle under stress. If the vehicle should hit a boulder or a tree stump, the wheel rim would lose its verticality and, so close to the side of the body, could damage that as well as itself. The present reconstructions of the Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero vehicles above the axle level raise many doubts and questions, but one cannot argue about something for which there is no evidence (FIGURE 4). It is from the wheeltrack measurements and the dimensions and positions of the wheels alone that we may legitimately draw conclusions and these are alone sufficient to establish that the Sintashta-Petrovka vehicles would not be manoeuvrable enough for use either in warfare or in racing.“

And in the introductory section, the authors already summarised the above conclusions with “these dimensions would render the vehicle impractical at speed and limit its manoeuvrability. These cannot yet be true chariots.“

Littauer and Crouwel have extensive familiarity with the mechanics of wheeled vehicles. Anthony and various others may have more general knowledge of it, but this has led to unsustainable conclusions.

I think these practical, evidence-based conclusions also override the experimentally derived ones from Chechushkov et al 2018. Maybe one of the reasons the Sintashta vehicles did not develop beyond grave goods is because they weren’t very usable.

There’s no support in the above extract for the views popularly expressed in various quarters about Sintashta being “warrior badasses” on account of their two-wheeled vehicles. If they’d have invested as much time in reading the research on it as they have in promulgating mistaken views about it, they would have discovered the Sintashta vehicle may have proved a liability rather than an advantage in warfare.

The chariot from 2500 bc that Rob’s linked page cited from Littauer was referred to in general terms as a chariot. My understanding has been that the true chariots in the Middle East were to be from around 200 years after the upper limit of Anthony’s date for the Sintashta vehicles.

I recommend the full Littauer & Crouwel 1996 paper. Its introduction additionally may be referring to the earliest Near/Middle East war or true chariot, when it mentions this contrastively against the ones that had been claimed as true and war chariots in Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero.

It definitely mentions very early spoked wheels in Mesopotamia that become older than the Sintashta one if the latter’s spoked wheel imprints are from 1600 bc instead of 2000 bc. However, without needing confirmation for Sintashta’s early date, Littauer and Crouwel provided reasoned arguments why the Near/Middle East is nevertheless the more likely source for the invention of spoked wheels.

> This kind of symbolism is important and mostly ignored when interpreting the Rigveda as a proof of a steppe origin of the Aryans.

What is then your current opinion, if you’ve formulated one (or more), as to the origin of the Aryans, that is, Indo-Iranians? And what is your reasoning for it?

I think it is also worth noting that horse domestication in Central Asia may be very old and not derived from the steppe

http://briai.ku.lt/downloads/AB/11/11_014-021_Lasota-Moskalewska,_Szymczak,_Khudzhanazarov.pdf

DELETED COMMENT

@ak2014b

Thanks for the information. I can’t really have a final take on where did true chariots originate without carefully re-examining all the data (and even then I might still have no certainty about it), but my take is that it’s not a fundamental thing regarding historical events.

Re: the origin of Indo-Iranians, I wish I knew! I’m not arguing for a specific place of origin, since I don’t know where it was (no one does). My argument is more against assumptions and forced arguments to favour a specific hypothesis. And against the interpretation of a mere hypothesis as a reality (or almost), when it’s actually based on weak evidence.

I’m not against Indo-Iranians having an origin on the steppe. Even if the evidence is weak when looking at it objectively, it’s still a realistically possible option. And there are not that many options that are realistically possible, so I’m not going to discard the steppe one. I’m just waiting for more data that allows for a more solid argument either way.

I think that this will come from samples from the core areas of the early Vedic cultures (around the Punjab, ca. 1900-1400 BCE). Depending on what they show the constraints on the origin of Indo-Iranians are going to be much tighter. I guess there are 3 main possibilities regarding what those samples can show:

1 – A clear continuity with previous population without any significant admixture from either BMAC or the steppe_MLBA.

2 – A significant admixture from BMAC but not from the steppe.

3 – A significant admixture from the steppe (with or without significant BMAC admixture).

I can’t help to regard the third option as the least likely given what we know so far. But we’ll have to wait and see.

@Jaydeep

Yes, that’s an interesting paper. For a while I thought of the possibility that the people who might have tamed/domesticated those horses in Uzbekistan (or just hunted them) might have moved north with the desertification of the area and could be related to the later Botai people. Now that we have DNA from both of those places this is not an option anymore, so it seems that this possible early horse domestication was just a dead end.

@aryanblood

I already told you before that this is not the place for these kind of comments that are not based on correct facts and their only purpose is to start some “ethnic wars”.

> I can’t really have a final take on where did true chariots originate without carefully re-examining all the data (and even then I might still have no certainty about it), but my take is that it’s not a fundamental thing regarding historical events.

I agree there’s no actual final answer to the question of origination with what data we have presently. But the value of the steppe evidence has been over presented.

My comments about chariots and spoked wheels are not to make any case about their relevance to IE or human history, but rather concern the documentation of history. There’s too little actual evidence from Sintashta to justifiably compete with the clear and well-dated evidence we have from the Near East for both innovations. Even so, the steppe is still accredited both popularly and in many research works up to the present for originating spoked wheels as well as true chariots. It is a great assumption that rests on too many uncertainties. (And there is simply no need for it when there are better alternatives for consideration.)

A certainty we do have is that the steppe had spoked wheels, somewhere between 2000-1800 bc else 1600 bc. Using Anthony’s dates from the horse bones, which are the earliest that may be assigned to the vehicles, this being still 2000-1800 bc as per the cited paper, the interval makes it contemporaneous with the evidence of vehicles with 2 spoked wheels from Anatolia and Mesopotamia that were harnessed to equids. The paper by Littauer and Crouwel contains an image from Anatolia from the early 2nd millennium bc, showing a figure carrying a weapon standing on a vehicle with 2 spoked wheels. (The harnessed draft animals further look to be horses not asses in my interpretation.)

Consider again this statement from Littauer & Crouwel 1996,

“Let us consider what is actually known of the Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero vehicles. At Sintashta, there remained only the imprints of the lower parts of the wheels in their slots in the floor of the burial chamber (FIGURE 1); Krivoe Ozero also preserved imprints of parts of the axle and naves.”

Therefore the totality of the evidence from the steppes is comprised of imprints from the lower part of the vehicles: the wheels, axle and the wheel hubs (naves). The rest of the steppe vehicles have been entirely reconstructed by researchers: as chariots, even though the same and actual evidence lends itself equally to their reconstructions as carts, as Littauer pointed out earlier.

Littauer & Crouwel 1996 found the reconstructed portions questionable, “The present reconstructions of the Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero vehicles above the axle level raise many doubts and questions”. Nevertheless, the paper’s authors allowed for both the reconstructions and the earliest dates (those of the horse bones assigned to the vehicle) in order to come to the conclusion that, despite this, the two wheeled steppe vehicles were still not true or war chariots. The authors made these allowances for the sake of argument. There is no real reason to continue making them when considering the earliest indisputable evidence available for both spoked wheels and chariots.

Clear cut evidence may conceivably turn up in the future, possibly from the steppe, that dislodges the Middle East from its present position as attesting to the currently oldest instance(s) and being the tentative origin for the true chariot and spoked wheels. Until such a time though, I believe the ancient Near East and not the steppe ought to be recognised as holding this position, whether the innovations themselves be important in any sense or not.

I’m sorry to have consumed so much of your time with this, the point was a more general one and may not have stood out given the context of aDNA and IE.

I remember a couple of remaining questions I had. It concerns the following extract from https://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/22/science/remaking-the-wheel-evolution-of-the-chariot.html

“Chariot technology, Dr. Muhly noted, seems to have left an imprint on Indo-European languages and could help solve the enduring puzzle of where they originated. All of the technical terms connected with wheels, spokes, chariots and horses are represented in the early Indo-European vocabulary, the common root of nearly all modern European languages as well as those of Iran and India.

In which case, Dr. Muhly said, chariotry may well have developed before the original Indo-European speakers scattered. And if chariotry came first in the steppes east of the Urals, that could be the long-sought homeland of Indo-European languages. Indeed, fast spoke-wheeled vehicles could have been used to begin the spread of their language not only to India but to Europe.”

Firstly, is it true that vocabulary related to chariots is shared in Indo-European? The discussions on eurogenes led me to believe that chariots were originally associated with Indo-Iranian.

Second, the current situation is that there are yet no definite chariots in the steppes, since the Sintashta and Krivoe Ozero may as likely be carts. What seems to me more pertinent is there was no tradition of two wheeled vehicles in the steppes until these finds, going by the extracts from Littauer & Crouwer 1996 further above. (It was one of the reasons Littauer and Crouwer argued that two-wheeled vehicles on the steppes were inspired by those in the Near East, thereby also explaining their sudden appearance on the steppe.)

As chariots are two-wheeled vehicles, do the first and second points not conflict? If, as Izbitser’s work based on the evidence of wheeled vehicles in the steppe is to have argued, the steppe were inhabited by “people without a history of two-wheeled vehicles” (Littauer & Crouwer 1996) until the Sintashta era finds marked a distinct change, how may the chariot terminology be part of “the early Indo-European vocabulary, the common root of nearly all modern European languages as well as those of Iran and India”?

If not the immediate conclusion that the steppes as a consequence cannot be the homeland (or that chariot is not part of the PIE or LPIE vocabulary), maybe the argument has to become that chariots were borrowed early on into PIE, to explain the absence of the development of two-wheeled on the steppe? However, won’t the same long-term absence of two-wheeled vehicles in the steppes condense the timeline for PIE in a steppe homeland?

@Alberto

> For a while I thought of the possibility that the people who might have tamed/domesticated those horses in Uzbekistan (or just hunted them) might have moved north with the desertification of the area and could be related to the later Botai people. Now that we have DNA from both of those places this is not an option anymore, so it seems that this possible early horse domestication was just a dead end.

Is the above saying that we have horse aDNA from Uzbekistan and the Botai and the former is not ancestral to the latter and therefore a dead end? Or the former has been found ancestral to the latter and is a dead end because the Przewalski horses deriving from Botai are not ancestral to modern domesticated horses? Or we have human aDNA from Uzbekistan and from Botai and the former is ancestral to the latter and are a dead end because Przewalski horses are not relevant to modern domesticated breeds, though that doesn’t match “this is not an option anymore”? Or we have human aDNA from Uzbekistan and Botai and the former is not ancestral to the latter? But in this final scenario, I’m not following how it connects up with the horses of unrelated populations, unless the ancient inhabitants of Uzbekistan became largely extinct along with whatever kind of horses they had.

@ak2014b

As far as I know, it’s the words related to wheeled vehicles in general and not to chariots in particular (except for the word for horse itself) that is considered part of PIE (or better to say, late PIE, since Anatolian languages don’t share this vocabulary). The article from Anthony and Ringe linked in the post have a more detailed discussion about the terms and their appearance in each daughter language.

Or we have human aDNA from Uzbekistan and Botai and the former is not ancestral to the latter? But in this final scenario, I’m not following how it connects up with the horses of unrelated populations, unless the ancient inhabitants of Uzbekistan became largely extinct along with whatever kind of horses they had.

Yes, we have human DNA from Uzbekistan and surroundings going back to the Chalcolithic, and we have human DNA from the Botai people. The people from Uzbekistan are not ancestral to the Botai people. So apparently, the horses in Uzbekistan disappeared or migrated north, but the people remained (and adopted camels instead).

This means that the Botai people domesticated the horses independently of the possible earlier domestication in Uzbekistan.

Some thoughts on horse domestication:

1. We need to consider the possibility of several independent domestications of the horse (or maybe semi-independent, i.e. a certain group learning of tamed horses elsewhere, and then trying to domesticate local wild horses). Considering that Wutke e.a. 2018 identified four different haplotypes in domesticated horse aDNA, we may think of up to four different domestication locations (plus possibly Iberia, where an older study found DNA related to wild Iberian horses being incorporated into modern local breeds).

2. As concerns the Botai horse, the Wutke e.a. study demonstrates that it found its way into Central/ Western Europe. The earliest reported European occurrence of a domesticated Botai horse is from Westerhausen/ Harz (Bernburg Culture), and the latest one (early medieval) from Rathewitz, some 110 km SE of the former. Interestingly, a domesticated Botai horse was also found in Bell Beaker contexts in Zambujal, Portugal. Librado et al. 2017 had already shown that a Baalberge horse (ca. 3500 BC) contained a coat color gene only found among domesticated horses. In the meantime, for the Salzmünde horse burial (3300-3100 BC) the same gene was shown to have been present as well. So far, it is unclear whether the a/m were also of the Botai type, but the temporal and geographic proximity to the Bernburg Culture Botai horse makes this a likely scenario.

The often discussed similarity between PGerm *marhaz, PCelt. *markos “horse” (without other IE parallels), and Mongolian *mori “horse” hints at the (pre-Proto-) language that Botai people may have spoken, assuming that the domesticated Botai horse came to Central Europe with a corresponding term. Surprisingly, however, there so far have no Botai signals been found in Elbe-Saale TRB human aDNA, so the mechanism via which the Botai horse came there still remains a mystery.

3. – HT 1, dominating since the IA till to date, has earliest been found in Malé Kosihy on the Slovak-Hung. Border (2200-1600 BC, Hatvan-Otomani Culture), It seems to be related to what Gaunitz e.a. call the DOM2 haplotype that dominates modern breeds, earliest identified in a horse from Dunaújváros, 125 km S of Malé Kosihy (ca. 2000 BC, Vatya Culture). As Wallner e.a. (2017) have shown, this modern haplotype is of “oriental origin” (Arabian/ Turkmene horse) [https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(17)30694-2] .

Against this background, a possible early horse domestication in Central Asia, as suggested by you, Raydeep, is a fascinating idea. In fact, I don’t think that the evidence provided in the paper you linked is sufficient to demonstrate an early domestication in Uzbekistan – and even if so, domestication was apparently aborted there, so it is hard to imagine a direct descent of HT1 breeds from 5th mBC Uzbek domesticates. Nevertheless, the paper clearly shows that wild horses that phenotypically seem to be ancestral to modern “oriental breeds”, i.e. the Turkmene and the Arabic horse, were present in Central Asia.

4. Surprisingly, no one here has yet mentionned Alikemek Tepesi (SE Azerbaijan) as likely domestication location, acknowledged, e.g., by Anthony. Stratigraphy suggests intensive horse exploitation there since the early 5th mBC (Dalma pottery horizon). Bone analysis by French researchers is under way – let’s wait and see what they will come up with. Frankly, I don’t have any idea how the Alikemek Tepesi horses may have looked, i.e., whether they had the “oriental” (Turkmene) phenotype. However, SE Azerbaijan isn’t that far away from Turkmenistan to make this unthinkable…

5. – Acc. to Wutke e.a., HT 3, most frequent during the BA, has earliest been identified from Kirklareli, Turkey (Black Sea Coast, 2700-2200 BC). If B. Arbuckle is correct with proposing an independent horse domestication in Anatolia, HT3 appears to be the most likely outcome of such efforts.

In this context, R. Hauser “Reading Figurines from Ancient Urkeš (2450 B.C.E.) ” [www.urkesh.org/attach/Hauser%202015.pdf] is a worthwhile read: “Archaeological evidence shows that equids were present [at 3rd mBC Urkesh]; morphological change as represented in terra-cotta representations of Equus documenting domestication occurred.” However, that process apparently post-dates the appearance of domesticated horses at Botai and possibly Alikemek-Tepesi.

6. – Finally, there is Wutke e.a. HT 4, relevant until the Iron age, but not identified afterwards. Their earliest reported occurence is from Mayaki, SW Ukraine (3800-3100 BC, Lower Mihailovska Culture, a CT offspring) , as non-domesticated (hunting prey?) Domesticated, it appears in EBA contexts from Schlossvippach (Unetice) and Malé Kosihy (2200-1600 BC, Hatvan-Otomani Culture), and is for the IA a/o reported from Belgium, Denmark, Georgia, and Arzan, Tuva, S. Siberia (Scythian graves). The pattern suggests domestication (or in-breeding?) in the Western Steppe, presumably not earlier than the mid-4th mBC, and subsequent spread alongside human Steppe populations.

@ak2014b – re Anthony’s “wheel” terminology:

Among the PIE roots highlighted by Anthony is *kʷékʷlos “wheel”, reduplicated from *kʷel- “to turn”. This root, however, isn’t anything but proprietary to IE. S. Nikolaev, e.g. reconstructs Proto-Algonquin-Wakashan (PAW) *k’ʷi:lk’V “to roll, turn” (unlikely to have been borrowed from PIE, since Amerindians didn’t know wheels prior to Spanish arrival). Note also

– PUralic *kerä, re-dupl. *kečke-rä “round”, Zyrien gegil “wheel”;

– Sum. girgir “chariot”, redupl. from kir “to roll”,

– Semitic *galgal “wheel”

– Swahili gaga “to roll” (but gurudumu “wheel”)

IOW – at least this part of Anthony’s evidence stands and falls with the assumption that the wheel was invented by PIE speakers, and the root was subsequently borrowed into other languages (which still doesn’t explain the PAW and Swahili forms).

So far, however, the earliest safely dated evidence of wheeled vehicles is from Flintbek (TRB N), Warburg (Wartberg Group), and Bronocice (TRB SE), all around 3,400 BC, and unlikely to have spoken IE. Contenders, which so far lack reliable AMS dating, include Sumerians, CT, Maykop-Novosvobodnaya, and the Horgen Culture (Zurich lake wheel finds). Of all the above, only Maykop-Novosvobodnaya may have spoken PIE, though that is also being questioned after the recent analysis of Maykop aDNA.

@FrankN

Though I would say that the haplotypes in horses don’t identify the population to whom they belong. Early domestic horses and all modern domestic ones form a genetic clade to the exclusion of Botai horses (and Przewalski). So those domestic horses that carry HT-2 are not Botai horses. They are part of the population that was domesticated and survived to our days (even if the haplotype itself didn’t). This can be seen on the PCA in the first figure of the post.

That’s why to answer the question about the place of domestication we need autosomal genetic data from wild horses from each candidate place. The ones that form a genetic clade with early and modern domestic ones will tell us that they are the ancestors of all domestic horses (even if while expanding they got some admixture from other wild horses from different places, since that was not enough to make them distinct as to form a different population).

While I am at it (and to buy some time for my upcoming post on TRB-Sorsum), let me repeat and set forth here an issue that I already commented upon at Eurogenes, a page some of you may for obvious reasons not have followed closely anymore in the past weeks:

An issue that has puzzled many linguists is the connection between PIE *hekwos and PNCauc *hičwi [c.f. Kabardian шы (šə), Abkhaz аҽы (āčə), Avar чу (ču), Karata ичва (ičʷa, “mare”), Lezgi шив (šiv), and Hurr. ešša]), all meaning “horse” unless noted otherwise. The roots are obviously related, but don’t have any other “Nostratic” parallels, so one family should have borrowed from the other. But what was the direction?

A PNC->PIE borrowing would be phonetically straight-forward: PIE didn’t have the “č” sound, and, acc. to Starostin, regularly replaced PNC “č” with PIE “k”.

OTOH, PNC possessed the “k”-sound, and thus would not have needed to replace it with “č”. .As such, if the direction of borrowing was IE->PNC, the “č” in the PNC root requires borrowing from an already satemized source, i.e. PIA. However, this is chronologically problematic. Hurrian presence in N. Mesopotamia (Urkesh), and their possession of domesticated horses, is attested since (at least) the early 3rd mBC, i.e. contemporary with Corded Ware. If Hurrians stemmed from Kura-Araxes, as commonly believed, and received their ešša from PIE *hekwos, a satemised dialect (PIA) must already have been spoken around the N. Caucasus in the late 4th mBC. This scenario implies considerable dialectal variation, if not already a split into satemised (PIA) and non-satem IE languages (Proto-Hellenic, Italo-Celtic, Germanic) within (proto-) Yamnaya. Such split is not completely unthinkable of, but doesn’t really reflect the linguistic mainstream when it comes to (late) PIE.

Another problem is that Urkesh doesn’t lie on the archeologically evidenced trail of Kura-Araxes expansion. The assumption of Hurrian-KA association is based on a single feature, namely zoomorphic andirons, typical of KA, also having been found in Urkesh. However, such andirons are an extremely widespread phenomenon that, a/o, also reached the Western Aegaean in pre Mycenaean times, and as such rather an indication of KA cultural influence than of demic expansion.

Therefore, let’s consider an alternative scenario: Hurrian, and with it probably PNC [while some Russian linguists doubt the relation of PNC and Hurro-Urartian, the mainstream appears to see both as belonging to the same family] might be connected to Chaff-Faced Ware (CFW) that around 4,000 BC covered a wide area stretching from the Khabur valley around Urkesh in the West to NW Iran. The CFW horizon a/o included the Leila Tepe Culture in Azerbaijan and E. Georgia, Nakhkichevan, and also Areni cave (Armenia_EBA). It is archeologically, and – as far as I understand -also genetically, connected to Maykop, as such providing a plausible explanation for the current distribution of North Caucasian languages (Starostin has estimated the age of PNC at plus-minus 6,000 years, i.e. more-less contemporary with Maykop).

CFW connected two possible locations of horse domestication, namely Alikemek Tepesi (SE Azerbaijan) and Urkesh. For chronological reasons, I tend towards the former as original domestication area, but let’s wait and see what ongoing research related to both will ultimately yield. In any case, the “CFW ~ PNC/ Hurro-Urartian” homeland scenario could make PNC *hičwi, Hurr. ešša the original term for “(domesticated) horse”, to be subsequently borrowed by (late) PIE as *hekwos . [Note in this context also Ivanov (1999), who in a lengthy essay a/o argues that PHellenic *íkkʷos (OGrk hippos) “horse” must have been borrowed from PNC, as PIE *hekwos would have yielded “heppos” instead of “hippos”. ]

If that secenario is true, what does it tell us about the IE Homeland? Well, it can’t have been too far away from the CFW area. The Pontic-Caspian Steppe is one option. The other one is the Kura-Araxes culture that also expanded into the steppe (Daghestan), but in addition provides a link to Anatolia, the Levante, Cyprus, and ultimately much of the Mediterranean. I currently tend towards the latter because of Sumerian-IE language relations that may be best explained from the KA expansion into the Central Zagros – but that is an issue I will devote a separate post to.

@Alberto: “Early domestic horses and all modern domestic ones form a genetic clade to the exclusion of Botai horses (and Przewalski).”

Re-read Wutke e.a. (2018). This is what they state (1st paragraph under “Results and Discussion”): “Somewhat surprisingly, we also detected in several of the successfully genotyped aDNA samples the Przewalski horse haplotype (Y-HT-2), which differs at all four polymorphic positions from the present-day domestic haplotype.”

So, they identified domesticated Przewalski horses (HT-2) in Bernburg, and also Bell Beaker Zambujal. Since AFAIK there isn’t any evidence for the presence of Przewalski horses in EN Central Europe (you tell me about Iberia in this respect), the most parsimonious explanation is that we are dealing with Botai imports here.

However, the Przewalski horse is today found in Ukraine, and Wutke e.a. identified a non-domesticated HT-2 from Pietrele, Romania (Gumelniţa culture, probably described here: https://www.e-anthropology.com/English/Catalog/Anthropology/STM_DWL_kopF_qBP86IKHN4V8.aspx). As such, a SE European domestication of the Przewalski horse – whether related to, or independent from Botai – cannot be excluded.

@FrankN

Thanks, very interesting comment about the ethymology of the word for “horse”. Now that 2 separate lines of evidence (autosomal divergence of domestic horses from Botai ones and the latest paper linked in the update) put into question the long preferred place for domestication in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, this looks more relevant than ever.

Re: Wutke et al., we should make a distinction between a Y chromosome haplotype and genome-wide genetic structure. It’s probably easier to explain with human DNA. For example, we have EEFs from Iberia with the R1b-V88 haplotype, which was first found in Mesolithic hunter-gatheres from Ukraine. Indeed, the Y chromosome of those EEFs is more closely related to that of the Ukranian HGs than to their fellow farmers from Iberia carrying let’s say G2a haplotype. However, genome-wide wise, they are almost identical and form a tight clade with the other Iberian EEFs and are very divergent from the HGs from Ukraine.

As such, what Wutke et al. seems to show is that the population of horses that was first domesticated possibly carried HT-2, HT-3 and HT-4 already (or at least they were introduced very early into the domestic pool so that we can’t tell with the current samples if they were introduced later on). However, HT-1 seems to have been missing in that early domestic population and only introduced into the domestic pool at a slightly later stage (see Fig. S1 from the supp.).

The reasons for why did a bottleneck occur a few thousand years after domestication to which only HT-1 survived is still unknown, though the authors hinted in some interview (don’t have the link right now) that they already have good clues about it (for a later publication).

Thanks Alberto and FrankN.

It’s not clear why the interviewee (Muhly) referred to chariots, and spokes too, as common elements in PIE vocabulary, if both are frequently described as associated with Indo-Iranian in specific due to the earliest finds being Steppe MLBA. Muhly’s reference to wheel and horse in PIE were instances I had already somewhat familiarised myself with, from Anthony and others, but I was not aware of the connections to other language families for wheel and horse pointed out by FrankN.

@FrankN

FrankN, your points once more contains lots of information new to me, so I don’t mind waiting a little longer for your next guest post, since your comments have once again been like guest posts in that sense.