The following post is written with two main purposes: The first one is to explain some of the problematic when dealing with substrates in a way that is accessible for anyone to understand and get a better perspective about this complicated subject. The second one is to take a look at how ancient DNA (aDNA) can help in solving part of this problematic (in this sense, it’s a first addition to the “introduction” I wrote a while back).

For these purposes I’ll be looking at the subtrates in Iberia. There are two main reasons for choosing Iberia. The first one is that being part of the peripheral area of prehistorical West Eurasia is offers a relatively simple and straightforward population history, but unlike the rest of the periphery is also offers relatively early information about the languages spoken there (going back to the Iron Age). The second reason is that after the latest paper on the subject it’s one of the best sampled areas we have today when it comes to aDNA. A third, less important reason, is my own knowledge of its history and language, which makes is easier for me to write about it than it would be to write about any other place.

I will try to keep things as concise as possible, with a few short linguistic notes provided by Kristiina (see acknowledgements) marked with numbers (in red: note¹, note², etc… to avoid confusion with any phonetic symbol) and some other more extensive ones to add clarifications and additional thoughts marked with red asterisks (note*, note**, etc…, idem), the latter of which should not distract from the main text.

Basque and Iberian: and overview of their relationship

I’ll start with a short summary about the subject of the relationship between Basque and Iberian languages, since most of the literature about is available in Spanish and therefor less accessible for many readers.

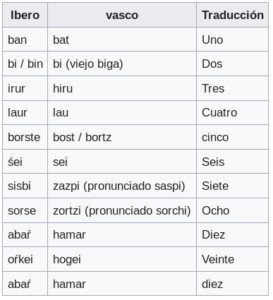

The history of Vascoiberismo (the hypothesis of these two languages being related) goes very far back in time, but it’s not until quite recently that the hypothesis has become widely accepted even by previously sceptic linguists. The main reason for this broader consensus has been the research on the numerals by reconstructing the proto-Basque ones and finding close similarities (far beyond coincidence) in the Iberian inscriptions, and in places (within those inscriptions) where one could (or would) expect to find a numeral.

Together with the same system for constructing the higher numbers, it has left few sceptics when it comes to accept the close relationship between both numeral systems. But the next questions was if this was a case of a wholesale borrowing of the numeral system from one language by the other or if it meant a genetic relationship (same origin) of both languages. Here is where there has been more debate, but in most cases the genetic relationship has been the preferred explanation*.

Moreover, given the aDNA that we’ve been getting in the last few years, the only plausible sources for these languages are two: the Early European Farmers (EEF) from Anatolia and the Bell Beaker Culture (BBC, ultimately from the steppe). With the relative proximity of East (including NE) Iberia and SW France (Aquitaine) – even with the Pyrenees as a barrier to strictly direct contact – and the very close genetic relationship of the involved populations, it becomes very easy to think that they are genetically related. I would go as far as to say it’s even necessary, since if they weren’t, that would force one to come from EEF and the other from BBC, preventing the possibility of the BBC having brought IE languages to Western Europe**.

However, if we accept a genetic relationship between the two languages, the following question might come to any readers mind: if these two languages were indeed closely related, why can’t we understand the Iberian inscriptions still? And that’s an important and very legitimate question, to which I can offer the following answer: The main reason why we can’t understand the Iberian inscriptions by using Basque as a reference is that modern Basque is a language that has survived rather miraculously into the 21st century. It’s not long ago that it was an endangered language mostly spoken in rural areas, some isolated from others, with different dialects not always easily intelligible among them. So it’s a very “drifted” language, only revived and standardized quite recently (as Euskera batúa, or Standard Basque), and with a limited native vocabulary (the larger part being borrowed from its neighbouring IE languages). So it’s not surprising that it’s still really hard to understand Iberian, even in the -more likely than not- case of it being genetically related to Basque. Another reason is probably the nature of the Iberian inscriptions that is mentioned further down.

A hypothesis about non-IE preroman Iberia

I will call this a hypothesis because it is not something completely proven. However, with what we know today it’s a solid hypothesis and not just pure speculation.

The main point of it is that the non-IE speaking areas of Iberia were first Indo-Europeanised by the Romans.

Given the population movements that we know about, it’s difficult to reconcile the idea that those areas were once IE and that later they became non-IE***.

So what follows will be based on this hypothesis, and it will be future research that should confirm or deny its veracity (though even if this hypothesis is falsified, it won’t necessarily invalidate many of the concepts I’ll comment about. It would, however, invalidate the specific examples used here based on it).

What is Indo-European?

The first thing we should clarify is what do we mean by Indo-European. It might seem a trivial question, but defining the meaning in a specific way is important to avoid misunderstandings while reading this text. So basically there could be two different definitions of IE:

- The language spoken by a population from a specific place at a specific time, before the dispersal/expansion and subsequent diversification of the language. I will refer to this a Proto-Indo-European (PIE)

- The language that expanded after that initial stage, succeeding and, to different degrees, absorbing many other now dead languages encountered along the way, most of which are completely unknown to us (and therefor have only reached us through the IE languages that absorbed them). I will refer to this as Indo-Europeanised (IE-ised).

While the second definition might be useful for some other fields, it’s clearly not too useful when it comes to determine the origin of the IE language (PIE) and its dispersal. So it’s important to keep in mind the first definition as the one that we’re going to need for this kind of research.

A preliminary look at the substrates in Iberia

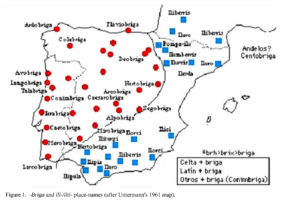

There has been a traditional divide in the Iberian toponymic areas based on the Celtic –briga and the Iberian Il-/Ili-/Ilti- respectively which matched the historical IE and non-IE speaking areas:

However, the situation became more complicated as more research was done. A big turning point was Francisco Villar’s work on toponymy (emphasis mine):

Recently, however, Francisco Villar (2000) has offered a new, somewhat revolutionary approach according to which there might have been a very old Indo-European layer that was particularly strong in the south. In my own work (see for instance 2003) I have also interpreted place-names as Indo-European that are found in regions generally considered non-Indo-European.

García Alonso, J.L. 2006. -Briga Toponyms in the Iberian Peninsula

This research brought back the Paleolithic Continuity Theory (PCT) which argued that IE languages were very old in Iberia (not exclusively in Iberia, needless to say), probably going back to the Mesolithic, and that non-IE ones were only a much later arrival. Now, this may sound very outdated in the aDNA era, but that’s just because of how fast things have moved in the last 5 years. In any case, this particular theory (the PCT) doesn’t really matter for the analysis of the substrates done by several authors.

To briefly show the results that this line of research has given, I’ll refer to a study which is in English and freely available (follow the link), by Leonard A. Curchin: NAMING THE PROVINCIAL LANDSCAPE: SETTLEMENT AND TOPONYMY IN ANCIENT CATALUNYA, 2006. ****

And I’ll start by just showing the statistical summary of the 97 toponyms (including hydronyms) analysed:

- Iberian names: 10 (10% of total)

- Indo-European names: 49 (51%)

- Greek names: 10 (10%)

- Latin names: 22 (23%)

- Unclear: 6 (6%)

Important note: Indo-European names refer to those that cannot be associated to any specific IE branch (including Celtic or para-Celtic), so they are just of generic/unknown IE origin.

So now one might wonder why is this. Why would Catalonia (in this specific case, but it’s a similar situation with the rest of eastern and southern Iberia) have only 10% Iberian toponyms? And why 51% IE ones, when it’s so unlikely that it was ever an IE speaking area before the Romans arrived? And which IE language would that be, unrelated to Celtic or any other specific branch, some sort of PIE?

Before moving onto those questions, let’s ask ourselves once again:

What is Indo-European? (Part II)

As already mentioned in the first part above, what we are interested in is the language spoken by the original population before it expanded. That is, PIE. So let me quote here something that Kristiina, a regular commentator well knows by the readers here, has mentioned a few times:

The amount of roots having more or less the same meaning is very high in the presumed IE vocabulary. In Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture by Mallory and Adams there are 18 roots for ’bend’, twelve for ’bind’, seven for ’branch’, twelve for ’burn’, six for ’fear’, seven for ’field’, seven for ’goat’, seven for ’grain’’, eight for ’grow’, five for ’axe’, five for ’water’ just to mention a few examples. Modern developed languages usually have only one or two.

So it seems like a very pertinent question to ask if all those roots belong to what I’m referring to as PIE or to what I’m referring to as IE-ised. And while I’m sure the answer is more or less obvious to any reader, let’s consider a few issues here.

First, what is it required for a word or root to be considered PIE? Is there a standard widely accepted by all the experts in the field to accept or reject a proposal for considering a word as PIE? As far as I know there isn’t such thing (and knowing how linguists tend to go their own ways rather than cooperate in solving problems, it’s hardly surprising if there isn’t any standard for such a basic and important thing). And if there is, what is it? Is it enough if at least two words in two different languages can be reconstructed following the regular sound changes in each to the same hypothetical PIE root? And if two languages are enough, can they be any two languages (say, German and Russian or Latin and Lepontic)?¹

So let me do a little experiment by proposing this simple hypothetical standard:

- A word/root can be considered PIE if it is attested (with regular reconstructions from the putative PIE root) in at least one language in each of these two groups (Group A and group B), and being attested in a minimum of three of them in total.

- Group A: Greek (ancient, here and onwards unless specified as ‘modern’), Latin and Celtic.

- Group B: Anatolian, Indo-Iranian (again, ancient unless specified otherwise) and Tocharian.

The reasoning here is that the languages in these two groups are less likely to share post IE expansion vocabulary, because they are ancient ones (even if Tocharian is attested quite late, but its isolation helps to keep the chances of later borrowing from Group A languages) and there’s not much evidence of later contacts (though the case of Indo-Iranian might be debatable until we don’t figure out its specific origin).

With this hypothetical standard in place, how would some of the presumed IE roots fair when measured against it? Well, this is a labour that I can’t do here in any great extent, so I’ll just look at a few cases based on the following resource which is easy and accessible to everyone:

Holm, Hans J. (2016, in progress): >Indo-European Universal Concepts List (M. Swadesh’s 1971=final meanings). With “unmarked” translations in 17 representative extinct and modern IE languages. From http://www.hjholm.de/.

- Water: 7 different roots are mentioned. The first one², wód-r̥ {sing}, auwed-(r)– < h₂wédōr {koll}, would comply with the requirements mentioned above, as it is attested (from that list of 17 languages) in Russian, Lithuanian, Old Icelandic, Norwegian (Bokmål), Old Irish, Modern Irish, Latin, Albanian, Greek, Hittite and Sanskrit. The second one, h₂ekweh₂– ‘(running) water’, only appears in Italian and Latin (aqua, also present in other Romance languages) in that list, so it wouldn’t comply. From the other 5, if we accept what are marked as “deviant meaning”, one of them, ap– < eh₂p– ‘water, river’³, appears in Greek, Hittite, Tocharian B, Avestan and Sanskrit, so it would qualify too. Overall, 2 out of 7.

- Sun: 6 roots are listed. One of them would qualify (1 out of 6)

- Leaf: 1 out of 12 listed would qualify

- Woman: 1 out of 7.

- White: 1 out of 12.

- Knee: 1 out of 3

- Moon: 1 out of 8

- Green: 1 out of 8

- Man: 2 out of 10

- Liver: 1 out of 9

I certainly can’t certify the accuracy of either the list provided above (it’s marked as a “work in progress, for lexicostatistical purpose only”), nor the validity of either the example standard I proposed or the precise counting of how many roots conform with it if confronted with additional resources. However, I think that the picture is clear enough to say that those details would only increase the accuracy (probably adding a small number of words to those that qualify) but wouldn’t change the outcome overall.

So to reiterate: PIE is not the same as IE-ised. And while setting some standard can mean that we leave a few real PIE roots out because we can’t prove them reliably enough to be PIE (that’s always going to be the case, not just with this specific subject), it’s still a better situation than throwing everything into the (same) basket.

Back to the substrates

So with this in mind let’s get back to the substrates in Catalonia and hopefully we can now understand better the reasons for those statistics. But first let me point out an additional methodological limitation which is mentioned in the paper (emphasis mine):

Such an inquiry [about the substrates] is not without difficulties. For one thing, we have only a limited knowledge of the vocabulary of Iberian, which is not related to any other known language, and can only identify toponyms as “Iberian” if one or more of the name elements appear in Iberian inscriptions (which consist largely of personal names).

This makes it probably easier to understand why we can only identify 10 toponyms as Iberian. You simply can’t say that something is Iberian unless you have an Iberian inscription with an equivalent name (root, prefix, suffix,…)to prove it. Given the very limited Iberian corpus, you can expect to find very few coincidences.

How about Indo-European? Well, the Indo-European corpus is enormous, from ancient to modern languages. With the problem of considering everything as IE (PIE and IE-ised), the amount of presumed IE vocabulary is so extensive that it’s difficult not to find coincidences, specially if you don’t restrict yourself to any specific language(s) known to have been spoken in the area or surroundings. This results in a very strong bias that only has gotten worse with time:

In fact the situation is much more complicated. In recent years, several Catalunyan place-names previously assumed to be Iberian have been reinterpreted as Indo-European by F. Villar (2000), raising questions about early Indo-European settlement in this supposedly non-Indo-European zone.

The result of this methodology is the one we already know from the aboe statistics: 51% Indo-European toponyms (but of an unknown branch) vs. 10% Iberian and even 23% Latin. When you consider that this is in an area where we know securely that non-IE was spoken and have attested and readable inscription of it, It’s hardly surprising the difficulty in finding non-IE substrates in places where there is not even an attested language before Indo-Europeanisation (like the rest of Western Europe).

Now, for the same of completeness, let’s take a quick look at the toponyms themselves. The paper lists them in alphabetical order, starting with river names. So to avoid any case of cherry picking, I’ll follow this same order:

Alba (Pliny III, 22). This clearly comes from the IE hydronym *albho– (IEW 30). Parallels include the river Albis (Elbe) in Germany (Tac. Germ. 41) and the river Albe, Albas or Albula in Italy, an early name of the Tiber (Pliny III, 53; Steph. Byz. s.v. Albas).

The IE root *albho–⁴ means ‘white’, which is unrelated to water, flow, etc… We have many red rivers, which have an evident explanation due to the colour of their waters, be it due to oxides or anything else. So I guess there’s something (freezing in winter, snow?) about these rivers that can justify them being called ‘white’? But more importantly, is the root PIE or IE-ised? Checking again the aforementioned list, it appears in Russian, Lithuanian, Latin and maybe Greek (Ἀλουίων, Albion?) and Armenian (aɫauni, ‘pidgeon’, ‘dove’). Apparently there’s also the Hittite (alpas) meaning ‘cloud’, and the Sanskrit ऋभु (ṛbhú) meaning ‘skillful’, ‘expert’, ‘master’.

Anystus (Avienus 547). While Pokorny saw this name as Illyrian, comparing the Bulgarian river Andzista, Schulten more reasonably interprets it as Greek anystos [ᾰ̓νῠστός] “practical”; thus, “the useful (river)”. However, the possibility remains that it is a hellenized transliteration of an indigenous name: cf. the river Anisus (modern Enns) in Noricum, which Anreiter et al. relate, not very convincingly, to a supposed IE *on– with hydronymic suffix *-is-.

Not sure if this counts as Greek or Unclear. Probably the latter, so not much to comment.

Arnus or Arnum (Pliny III, 22). Pliny gives the name in the accusative, which leaves the gender uncertain. Various hypotheses have been advanced: Pokorny made it Illyrian, Garvens Basque, while Jacob derived it from a supposed theonym Airo. Its true root is surely the IE hydronym *ar– with secondary suffix –no-. Cf. the Italian river Arnus (modern Arno).

If its true root is surely the IE hydronym *ar–⁵ I guess there’s not much to discuss either.

Baetulo (Mela II, 89). See below on the city of the same name.

Baetulo (Mela II, 90; Pliny III, 22; Ptol. II, 6, 18). Like Baecula, this name could be formed from IE *gʷhei-. However, the word baites which appears repeatedly in Iberian inscriptions on lead shows the possibility of an Iberian origin. The suffix –ulo is a latinized form, as shown by the orthography baitolo on the town’s pre-Latin coinage; cf. the classical spelling Castulo for indigenous kastilo in Oretania.

Let me complement it with the referenced Baecula which appears just above it in the paper:

Baecula (Pliny III, 23; Ptol. II, 6, 69). Villar derives the element bai– in various Hispanic toponyms from IE *gʷhei– “to shine, be white” (IEW 488-489), though the Iberian personal name baikaŕ may argue for an Iberian root *bai– or *baik-. In any case, there is no guarantee that all bai– toponyms (e.g. Baetis, Baedunia, Baesucci, Baelo) come from the same root. Polybius (X, 38, 7) mentions another Baecula in Bastetania.

So again I’m not sure if these two count as Indo-European or as Iberian or as ‘Unclear’. The proposed IE etymology doesn’t look very solid, if one has to be honest. Once you allow for such speculations you’re in a very muddy terrain. The Iberian one is not much more solid, but we have to realize the difficulty of finding such coincidences in the limited Iberian inscriptions. And yet they do look more similar, I’d say?

I won’t go on, since the paper is available for anyone interested in it. This was just to show how it works to try to figure out the true etymology of an ancient toponym and how difficult it actually is.

Conclusions

Since I think the above should be self explanatory it seems unnecessary to summarize it here. Instead, I’ll go back to the proposed hypothesis about the non-IE speaking areas of Iberia having been Indo-Europeanised only with the arrival of the Romans. If this is true (and it most likely is), then this is an opportunity to rethink some paradigms. Except for the 10% Greek toponyms and the 23% Latin ones, everything else would be non-IE. What should we do with that ~50% presumed IE substrate in these areas? For a start, we could use it to clean up roots we consider IE and probably shouldn’t. As a real world vocabulary attested before any IE speaking population set foot on the areas, that would be a pretty strong argument for disproving the presumed IE etymology of them (though this does not preclude the necessity of having a standard for what can be considered PIE, as that would make a big difference too). Equally important is the affiliation of such substrate. And here again we’d have to favour quite strongly an Iberian origin of most of it (though there’s the risk of ascribing pre-Iberian substrate to the Iberian one – a risk that is unavoidable but not that big considering the possibilities it opens up). Once we have a much larger non-IE lexicon from Iberia, we could go and compare that to the rest of Western Europe (to start with) and see what happens. It might be the way forward to finally shed some light on the obscure European prehistorical linguistic situation.

aDNA is speaking to us. We might still not fully understand the message, but we have to try so that progress can be made. This post is just an amateur attempt to show its possibilities. It’s now the experts’ job to make good use of all the new information we’re getting on a monthly basis and start building new models, which I hope will happen soon so we can all learn from them.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Kristiina for her help with this post, for sharing resources, providing linguistic notes and valuable feedback.

Linguistic notes:

1 – As a reference, Kristiina points out to me that the criteria for a Proto-Uralic for being considered as such is not very clearly defined either. She recalls the minimum requirement being that the cognate word exists in an Eastern Uralic language (Ugric or Samoyedic) and a Western Uralic language (Permic, Volgaic, Baltic-Finnic and Saami). I’ll leave it to her to elaborate further on this problematic at some point.

2 – However, she points out that the Pan-Uralic word for water is almost identical and shows regular sound changes (link)

3 – Though for this one it could be relevant to mention the Sumerian ‘ab‘ (‘sea’) or the Basque ‘*ɦibai‘ (‘river’).

4 – This root can hardly be considered the common word for ’white’ and ’light’ in IE languages. The basic meaning appears only in Latin, Umbrian and Greek. The Baltic and Slavic cognates mean ’lead’. The Celtic distribution is very scarce, the root ‘elbid‘ is only found in ancient Welsh and in no other Celtic language. It could also be a substrate word https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/albus#Latin

5 – It should be noted, however, that Basque possesses the roots ur ’water’, jario ’flow’ and gernu ‘urine’.

Extended notes:

* For example, Francisco Villar, a prestigious Spanish linguist specialised in IE and strong proponent of a some sort of “everything IE” (more about it in the main text), changed his sceptic view about Vascoiberismo due to the recent advances made in that field:

“En los últimos años se han producido ciertos resultados de la investigación en el ámbito de los numerales que han llevado la cuestión a un terreno más firme. Con los numerales incorporados al elenco de coincidencias, el parentesco entre ibero y euskera me parece ya la única hipótesis sostenible. La amplísima coincidencia en el sistema de los numerales señalada primero por E. Orduña (2005, 2006, 2011) y ampliada y consolidada por J. Ferrer i Jané (2009), especialmente (aunque no sólo) en los 10 primeros numerales, descarta en mi opinión cualquier explicación por préstamo. De hecho encuentro entre los numerales ibéricos y los euskeras no menos ni peores que las que en realidad se dan entre las lenguas indoeuropeas históricas.

Por añadidura, la hipótesis de los préstamos del íbero al vasco, aparte de su inviabilidad para el sistema de numerales, siempre ha tenido el punto débil de la falta de evidencias en favor de un contacto real entre ambos ámbitos incluso desde el punto de vista geográfico.“

Villar, F. 2014. Indoeuropeos, iberos, vascos y otros parientes

My translation [and emphasis]:

“In recent years there have been some results from the research in the field of numerals that have brought the question to a firmer ground. With the numerals added to the list of coincidences, the relationship between Iberian and Basque seems to me the only sustainable hypothesis. The extremely broad similarity in the numeral system pointed out first by E. Orduña (2005, 2006, 2011) and extended and consolidated by J. Ferrer i Jané (2009), specially (but not only) in the first 10 numerals, discards in my opinion any explanation by loan. In fact, I find between the Iberian and Basque numerals no less nor worse [coincidences] than the ones that actually exist between historical Indoeuropean languages.

Moreover, the hypothesis of a loan from Iberian to Basque, aside from its infeasibility for the numeral system, has always had the weakness of the lack of evidence in favour of a real contact between both cultures even from a geographical point of view.“

The infeasibility referred to in the emphasised text refers to the extremely rare nature of a wholesale borrowing of the numeral system.

You can find more (in Spanish) by reading the authors mentioned in the above quote. For example:

E. Orduña, 2013. Los numerales ibéricos y el vascoiberismo:

“Abstract: In this work we examine the implications of the existence of a great coincidence between the Iberian lexical numerals and the Basque ones, thus applying this proposal to the Iberian lead of Ensérune, where we can observe that the possible lexical and morphological coincidences between both languages are not limited to the numeral system. Besides, some possible loan words from Greek to Iberian are proposed, and some aspects of the structure of the Iberian numeral system are revised.“

Regarding the critics, I can mention two authors. Javier de Hoz has admitted the validity of some of the correspondences in the numerals, but his own hypothesis about Iberian was that it was a lingua franca (due to it being the first one written and acquiring some prestige) and it was only native to the south eastern part of Iberia, so its use throughout a much larger extension (esp. the NE) was just for trading purposes. So he could obviously not accept a genetic relationship between Basque/Aquitanian and Iberian without first dropping his preferred hypothesis. I can’t discuss here the problems of his hypothesis about Iberian as a Lingua Franca, but anyone interested can check out this paper (in Spanish). Suffice to say that no one has really accepted it as valid except Joseba Lakarra, the other author who rejects the relationship between Basque and Iberian. His main argument (apart from supporting the one from Javier de Hoz) is that the reconstructed proto-Basque numbers proposed that match the Iberian ones are not a valid reconstructions according to his own ones. However, Orduña has argued that those former reconstructions match the proto-Basque most widely accepted and with a more secure chronology (Koldo Mitxelena’s), while Lakarra’s own reconstruction has a vague chronology and is much more insecure.

Francisco Villar (whom I’m quoting here because he’s a prestigious linguist, but mostly because of two other reasons already mentioned, namely, his previous scepticism about VascoIberismo and the fact that he’s neither dedicated to the study of Basque or Iberian, but an Indo-Europeanist who has no dog in this fight) has sided with Orduña in this last criticism too:

Por otra parte, la evidencia de los numerales me parece tan consistentemente apoyada en el Método Comparativo que me atrevería a afirmar que si resulta incompatible con el paleo-euskera reconstruido hay que proceder a corregir esa reconstrucción, que es hipotética y perfectible, como toda reconstrucción.

My translation:

Furthermore, the evidence of the numerals seems to me so consistently supported in the Comparative Method that I would dare to say that if it turns out incompatible with the reconstructed paleo-Basque one should proceed to correct that reconstruction, which is always hypothetical and perfectible, as every reconstruction.

Overall, while I can’t have a strong opinion about such technical debate, nor any preference over the relationship (or lack thereof) between Basque and Iberian, I do think it’s by far the most simple and consistent explanation. And as I said before (more about it in the second note) probably a necessary one.

** The possibility of Bell Beakers bringing IE languages to Western Europe, given the data that we have already for a while (and now with more detail thanks to the latest study recently published: Olalde et al. 2019) is a low probability one. However, it’s still possible and I personally prefer to leave that possibility open until we get a more detailed information about the period between 1500-700 BCE in Iberia, which is currently poorly sampled (plus some extra details from the transitional period ca. 2400-2200 BC).

The situation with the current data would be like this: Non-IE languages have 3 possible sources:

- Bell Beakers

- EEFs

- WHGs

While I would caution against the necessity of language shift with large population replacement, especially in the male lineages (as FrankN already wrote a while back), I’d also say that good reasons are needed to prevent language shift from happening in such scenarios. One thing usually mentioned when it comes to language shift is that language is imposed by the “winners” (be them a small elite or a larger part of the population). This is not completely accurate. Languages are rarely imposed. The main driving factor in language shift is convenience. People, whether elite or commoners, majority or minority, change their language to another one when, and if, they see some benefit (for their own interests) in doing so. The exceptions to this rule are mostly due to some sort of “nationalism” (in older times better referred to as “strong ethnic identity” – usually as a reaction to what is felt as an aggression from a different ethnic group) where ideological reasons would be placed above the practical ones.

In the case of this large population replacement throughout Western Europe during teh transition from the Copper Age to the Early Bronze Age, convenience does not seem like it might have been a strong factor in the incoming Bell Beakers to shift from their language to those of the previous populations that they were largely replacing. Therefor, the probabilities of those non-IE languages coming from the Bell Beaker side is very clearly higher than the other two (EEFs and WHG, the latter having close to zero probabilities).

When we get more samples from the mentioned periods, if there is any significant surprise then things could change and push the probabilities of Ibero-Vasconic coming from EEF. Difficult to say how much without knowing which surprises those may be. If, on the contrary, there are no surprises, then those chances would go further down, leaving Bell Beakers as the only realistic option.

One problem not mentioned yet is the relationship between Tartessian and Iberian. The reason is that there’s no real answer to it: whether they are related or not is unknown due to the very poor knowledge of the Tartessian language. If they could be proved to be non-related, then that would leave us with the only possibility of assigning Tartessian to that EEF population and Ibero-Vasconic to the Bell Beakers. But that’s really just speculation. It’s much more likely that Tartessian is actually related to Ibero-Vasconic, and that would still allow for the possibility of Bell Beakers to having brought IE languages to Western Europe (if we assign the non-IE ones to EEFs, that is). Those IE languages, in turn, would have gone extinct by the Iron Age without us having any notice about them, which requires a selective replacement of them by the para-Celtic and, specially, Celtic expansions. That is, these latter expansions would have completely replaced the IE languages brought by Bell Beakers to Western Europe, but left the non-IE ones originally from the EEFs untouched – once again a very low probability scenario.

Lastly, I will comment on another issue: the language diversity of the two main populations involved (EEFs and BBs, leaving WHGs out of the picture).

The case of EEFs is harder to analyse due to its depth in time. The idea that this population was quite homogeneous at the start of the European colonization seems quite solidly based. However, as they moved slowly throughout Europe, each group quickly lost contact with others due to the low mobility. We should expect that the Danubian and Cardial expansions diverged (linguistically) from each other quite significantly during the subsequent two millennia. The diversification in Western Europe was probably not as high, due to the later arrival and apparently being mostly of Cardial origin. In trying to quantify the degree of divergence we could take into account a couple of factors: Low mobility and isolation would increase divergence rate when compared to populations keeping closer contacts*****. But then not as much as interaction with native populations would do. And this lack of strong external influence would clearly slow down divergence when compared to scenarios with stronger interactions with local populations. Overall, I’d say that the languages of EEFs throughout Europe (maybe leaving aside complicated and less sampled areas like SE Europe), might have been in the range of Indo-European languages. That is, mutually unintelligible in most cases (geographically conditioned). Just like a Spanish speaker cannot communicate at all with a German speaker (or Russian, or Greek, or Armenian, or Hindi speaker), populations across Europe would probably be in a similar situation. Still, though, languages would be theoretically related if they could be studied by linguists.

When it comes to the Bell Beaker Culture, again we should assume an homogeneous population at the beginning of their expansion. Higher mobility would have contributed to lower divergence after the expansion. But interactions with local populations would have clearly accelerated it (the exception might be the British Isles, where little interaction seems to have taken place. But in Central Europe, France, Iberia or Italy the interaction and influence from locals would have been greater). The idea of the existence of a pre-Celtic language ca. 2500 BCE in Central Europe and the maintenance of a sort of language continuum throughout the subsequent 2500 years (something like the Roman Empire keeping Latin as a stable language, but for much longer – until the Romans themselves disrupted it) is completely unsustainable, though. The presumed IE substrate found throughout Western Europe (IE, but non-Celtic) would just add to the impossibility of such scenario.

*** Such scenario is clearly problematic. For a start, it lacks any sort of evidence, be it archaeological or genetic, and no one has ever postulated such hypothesis which means it does not have any support from any any point of view. But leaving that aside, we can try to check if it might have been possible in some way given that here we are interested in language, and that’s something that we have to analyse anew, with the latest data we have.

The possible scenarios that would be needed to justify the presumed linguistic substrates (shown in the main text), would be something like:

- EEFs bringing some early form of IE language with the arrival of the Neolithic to Western Europe. Then we would have the Bell Beakers from Central Europe (ultimately from the steppe) coming in and replacing those early IE languages with an Ibero-Vasconic ones, but nevertheless, and in spite of the language shift being accompanied by a large population replacement, leaving most of the place names intact, with only a minor impact in the subsequent 2000+ years.

- EEFs having brought non-IE languages and then Bell Beakers having replaced them with an early form of IE throughout Iberia (and Western Europe as a whole), and with it, replacing most of the place names, as one would expect. However, at a later point (800-700 BCE the latest, but excluding significantly earlier dates), a non-IE language expanding from “somewhere” all along Southern and Eastern Iberia, and reaching Aquitaine in South Western France.

I won’t extend in explaining the extremely unlikeliness of the first scenario because I’m sure that no one will agree with it. So let’s look at the second one to see how likely that can be.

I guess that the survival of some non-IE language in Iberia in the case of Bell Beakers bringing IE languages, with them and replacing most of the non-IE ones, is something perfectly possible. Some sub population could have adopted the local language for one reason or another. One problem though, is that after that, we need such population to keep that non-IE language for the subsequent ~1400 years in spite of them being surrounded by IE speakers (who in their surroundings would have spoken the same IE language and would have been able to communicate easily). This scenario requires a geographical (more likely) or some sort of ideological (less likely) isolation of the non-IE speaking population. Genetically, we could have them as either clearly shifted to the EEFs (low impact from the R1b/steppe Bell Beakers), or as just identical to the rest of the population (but then isolated and inbred for those ~1400 years, making them at least partly distinctive). Then it would be required for that population to have expanded -at least linguistically- during the first third of the 1st mill. BCE throughout the areas mentioned above.

While we still don’t have the kind of fine grained sampling required to judge in all its fairness such scenario from a genetic point of view, what we have so far does not suggest it in any way. We should be talking more about a cultural-linguistic expansion, something for which there isn’t any specific archaeological evidence either. So this would be a case of an “invisible” (genetically and archaeologically) linguistic expansion from an isolated population suddenly leaving it’s longstanding situation to somehow cause a linguistic shift throughout a vast, well connected (geographically and culturally – possibly linguistically), well populated area like the Mediterranean coasts of Iberia, and even reaching the quite less connected (geographically and culturally) Atlantic coast of Southern France.

Possible? Yes, but clearly not very likely. Probably below the realistic threshold already. And that’s without even factoring in the last step needed to complete this scenario, which is the selective replacement of old IE languages from the Bell Beakers by para-Celtic and Celtic expansions leaving non-IE ones intact, already mentioned in the previous note. And to add one more problem, with this late expansion of an IE language, it would seem unjustified that the Iberian and Aquitanian languages would have been called by different names, since they should have been very clearly related (just like the rest of Iberian ones). All of which makes an already unrealistic scenario become basically impossible.

**** This study is specifically about Catalonia, so some may wonder if the results can be explained by the Urnfield Culture influence in that area. But no, not really. In short:

- The Urnfield influence in the area is real, but it was a relatively short phase. Clearly not long enough to explain the results.

- The nature of the influence is mostly seen as a process where the Urnfield newcomers must have blended with the locals, resulting in an uninterrupted transition to the period of the Iberian Culture. If Urnfield people came speaking an IE language, it seems like it didn’t have any continuity and probably they adopted the local Iberian language early after their arrival.

- If Urnfield was an IE speaking culture, there’s ample agreement in that it must have been some sort of pre-Celtic, which would explain some para-Celtic linguistic influence in Catalonia. But yet such influence doesn’t show up in the study (nor Celtic itself) instead being an unidentified, generic IE substrate we would be dealing with.

- Whatever the case about Urnfield and Catalonia, we’re not talking about a phenomenon seen in Catalonia specifically, but also in the rest of non-IE speaking areas. So Urnfield cannot really explain anything in Catalonia, but even less so outside Catalonia (so it’s really irrelevant for the bigger picture).

***** I will note that Kristiina mentions the increase in WHG admixture seen in MN Iberia (a phenomenon, the increased WHG admixture into farmer communities that correlates with distance -from Anatolia- and time throughout Europe). Indeed, the possible linguistic consequences of these interactions will have to be investigated in the future. Unfortunately, right now it’s still difficult to say much without having further details about the nature of the interactions, how did the admixture occurred, how did male lineages from WHG come to replace most of the Anatolian ones, etc… For this, we’ll need even more dense sampling with lucky finds and in those use isotopic values to get more info too (we actually have one of this lucky finds since early on, the Hungarian sample from a farming context who turned genetically to be a WHG. It would be interesting to have isotopic values from this sample, code name: KO1, ID: I4971, to know if he grew up in the same place as the other samples and if his diet was the same, which could tell us if he was part of the community since a child -even though both parents must have been genetically WHG- or if he joined as an adult). Interesting in this respect is the very recently published study about the Megalithic phenomenon that we didn’t have time to comment (even when one of the authors is a collaborator of this blog), that helps to bring some insight into the societal structures of the Megalithic builders and opens the path for more detailed knowledge that could allow us one day to be able to say something meaningful about the possible linguistic influence of European hunter-gatherers in the farmer’s languages (though being very likely that the latter are long gone without any knowledge about them, it might all be restricted to loanwords that made it into successive languages).

Lots of food for thought, thank you. You’ve made very interesting and different application of what the aDNA findings thus far can tell us and what possibilities are now more or else less likely in light of them.

I would like to know if many linguists have started asking the same questions, of how much of the presumed IE vocabulary is originally IE (PIE). It’s an intriguing idea that more might be known of the preceding languages in parts of Europe if certain subsets of words were not taken for granted as being IE rather than IEised, in consequence of incomplete consideration being given for making the assumption in each case.

Also, great work by Rob and his colleagues on that Megalithic paper. Patrilineal aspects to Megalithic culture controverts what some earlier popularised suppositions on pre-IE Europe led me to believe, so in that respect this finding was surprising, but it does make sense.

@ak2014b

Thanks. As with any post concerning linguistics I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to make my point get through correctly, but it seems you really got it so that’s a good sign.

I would like to know if many linguists have started asking the same questions

Me too. But if they haven’t (not sure how many follow closely these latest aDNA studies) then I hope this post can reach a few of them and stimulate these kind of reflections. I’m eager to see what aDNA can bring to linguistics too.

But if that’s a too ambitious on my part, I hope that at least the post can serve the other purpose of giving some insights into the linguistic problems (of substrates, but even beyond that) to the people that do follow these studies but are less linguistically inclined.

>I won’t extend in explaining the extremely unlikeliness of the first scenario because I’m sure that no one will agree with it. So let’s look at the second one to see how likely that can be.

Not to be contrarian, but why do you consider this unlikely? Isn’t this exactly what one expect given the ancient DNA – linguistic change due to aggressively male-biased replacement but retention of the native toponymy. Just look at the toponymy of the Americas.

@Marko

I thought no one would be arguing for something like Renfrew’s Anatolian Hypothesis. Though in this case it would be with a twist to make it a bit more complicated: steppe migrations replacing IE languages, and later IE languages re-expanding again to replace steppe languages.

I guess it’s possible, and if this is the scenario you’d favour, maybe you’d like to elaborate on it? I’d welcome an alternative such as that one, as long as someone could make it credible.

The use of “white” in river names isn’t that odd, it could mean “clear” or “silver”. Several fish in Germanic languages have names derived from the same root (Dutch “elft” and “alver”). Anyway, there are a lot of American rivers called “White River” and German creeks called “Weissbach”.

On account of the possibility of a previous IE becoming Iberian speaking: Why not? It actually fits the scenario of BBC being IE speaking but eventually picking up the Iberian languages very well.

@ Alberto

I had to keep my last post about hunter-gatherers brief, but I suspect the rise of WHG in Iberia as the Neolithic progressed was mostly of exogenous origin (e.g. from France).

Generally in north-central Europe, much of the WHG/ EEF admixture occurred in the post -LBK (post-5000 BC) period. In areas such as Brittany, I think hunter-gatherer chiefs must have been marrying into Neolithic communities (for a good overview ”Dating Women and Becoming Farmers: New Palaeodietary and AMS Dating Evidence from the Breton Mesolithic Cemeteries of Téviec and Hoëdic. Rick J. Schultin”). A similar situation can be seen in ALPc, which despite close similarity to Starcevo, the male lineages are almost all I2a2.

In other areas, there was somewhat of an LBK collapse, e.g. middle Rhine. The interactions in the Michelberg culture seem interesting, and hopefully full genomic data will clarify who was being sacrificed in those pits. From 4000 BC, groups like TRB and GAC were expanding southward at the expense of older farming groups.

At the same time, Mediterranean Europe had its own set of interesting but low key interactions during the Neolithic-Copper Age. What the brief overview suggests is that ”WHG/ farmer interaction” was a variable affair, depending on time & place, with resulting different sociolinguistic vectors.

Therefore I think by 3000 BC, Europe would have been quite linguistically diverse. The unfolding evidence would suggest that the linguistic diversity must have been virtually erased during the BB transition; and given the nature & degree of change its hard to imagine any of the Megalithic langauges of Iberia surviving beyond 2000 BC.

This is an excellent article, real joy to read — and you have pointed out an obvious thing that I have somehow not been really aware of all these years — if you have so many reconstructed roots, and you’re not much restricted in meaning, you will likely find *something*. Any river can be big, small, white, black, red, dark, deep, slow, fast, cold, named after deers, ducks, otters…

BTW the PIE word for water is heteroclitic (has an -r/-n alternation, which is a very archaic feature) so it’s not likely a loan from Uralic. It’s (in my humble opinion) a relic from the Indo-Uralic era.

@epoch

“The use of “white” in river names isn’t that odd, it could mean “clear” or “silver”.

Yes, I don’t find it specially odd. My point is that it would be preferable to have an explanation to justify such name. When we have a “red” river (for example in Spain we have one called Río Tinto), the reasoning behind it is usually clear. This applies to most other names or rivers or seas (think Yellow River, Yellow Sea, White Sea or Dead Sea). However, if those “white” rivers happen to carry dark waters and show nothing to justify the name “white”, it becomes more of a stretch to prefer such etymology. It’s all about trying to be more strict with assumptions.

“On account of the possibility of a previous IE becoming Iberian speaking: Why not? It actually fits the scenario of BBC being IE speaking but eventually picking up the Iberian languages very well.”

I elaborated about the problems of such scenario in note ***. I don’t think that “eventually picking up Iberian languages” is a good enough explanation to overcome those problems.

@Rob

Yes, I think that those interactions between WHG and EEF need to be more carefully analysed than what I could do here (and what the current data allows, though we’re making progress thanks to researches like the mentioned one you participated in). Especially in the fringes of Europe (Atlantic, North and Baltic Seas).

Though as you agree in your comment, it might ultimately be a moot point, given that those languages most likely disappeared by 2000 BC or soon after. It may still explain several widespread words that appear in different language families, though.

@Daniel N.

Thanks! Very glad to see this can stimulate to rethink some assumptions that may need revision.

In reality, I bet Indo-European was actually spread with Y DNA I2 farmers straight from Anatolia up towards Cucuteni-Trypillia and from there to Sredny Stog (and Corded Ware), but this is all after the main advance of G2a farmers (one example is the Dimini invasion theory: Sesklo would be the G2a wave, Dimini this I2 wave). Yamnaya thus non-IE, and perhaps Mediterranean/Atlantic I2 farmers actually spoke some old IE language (idk about that).

All evidence, though, does point towards the Bell Beakers speaking Vasconic. I have my own personal theories, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we could go back in time only to see a Yamnayan speaking… Sino-Caucasian (and for whichever culture spawned L23, perhaps Orlovka or Khvalynsk, speaking Sino-Vasconic; and Central Asian M269 having branched off early to form Burushaski perhaps even as part of the Hissar culture – all this is structured according to Starostin but ignore the dating and Na Dene being the earliest split). I don’t know why people see Afanasievo as more likely Tocharian than the Tarim basin folk given the Tocharians were not around the Yenisei for one thing (and I think Afanasievans spoke Sino-Yeniseian). The two things hardest to explain would be Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dene (in the grander context of Dene-Caucasian). Sino-Tibetan, perhaps, spread with Afanasievo’s influence on introducing metallurgy to the Far East. Na-Dene is, however, heavily associated with Y DNA C-M217 and not to that Native American R1b, so I’m not really sure. Really though, this is exactly the same thing with e.g. Chinese (not associated with R1b), yet there is a semi-plausible hypothesis for Chinese contained within the Dene-Caucasian hypothesis ultimately from Afanasievan R1b (and of course, not all R1b, but only specific subclades). The Yenisei natives today are also almost exclusively Y DNA Q and C, when we know there was a likely elite Z2103 presence in Afanasievo. Almosan however is sometimes lumped into Dene-Caucasian with Na-Dene and that is associated with R1b. Now, it would be incredible to know which subclade this branched off from, however nobody is willing to test even a single Ojibwe R1b sample in-depth. All we know from available studies is that this R1b is almost entirely M269 and different to the Western European variety.

That point though, to me, is astounding. Absolutely nobody wants to look at those R1b subclades in-depth. What does this say about the state of aDNA researchers? Could it be the case that they are heavily influenced ideologically, rather than being brutal scientists? Listening to any talk from absolutely any of them, Reich included, certainly gives that impression. Want to see a similar example? This is one of the first results that came up for me when researching the Old Copper Complex of the Americas (first known examples of metallurgy, during the 4th millennium BC (probably not as old as 4000 BC though!) and right on top of Algic territory i.e. the area of Native American R1b): https://web.archive.org/web/20190424131553/https://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/iss/kap_a/advanced/ta_1_3.html

This is all working back from the idea that Yamnaya perhaps didn’t speak IE (while Corded Ware did), as their L51 cousins likely spoke Vasconic; and because Anatolian is extremely archaic and lacks the word for wheel in PIE as well as having lots of words relating to farming and other things that Steppe folk would be unfamiliar with.

Thankfully, however, the truth for most of this will be available eventually. We may never find out if the Solutrean hypothesis of Y DNA I/C seafarers was legit or not given the questionable status of Anzick-1 and easy monopolisation of remains from that period, but there are way too many samples out-and-about in private collections from later periods to be censored from examination forever. It only takes one sample. And it’s only a matter of time.

@Alberto

In your explanation you state that this scenario requires 1400 year of isolation and inbreeding. But that is obviously not true, as the area where Iberian and Basque were spoken were pretty large, about half of Iberia plus Aquitaine.

There is also this. You propose that one of the reasons Iberian isn’t so similar to Basque is because Basque is a very drifted language, and another is the limited nature of the surviving Iberian inscriptions. However, we also have the Aquitanian language, with a similarly limited nature of surviving inscriptions, but thightly related to Basque. So if Basque is a very drifted language, it was already very drifted before the Romans came.

That means two things: Basque and Iberian started to take different paths way before the Romans came and secondly, the numeral system which is so similar apparently did not drift. Hence the numeral system must be a loan. But the numeral system is the main reason to consider a genetic link. Whatever the link may be, by the time we can attest them they must already have been growing apart for a long time. Is 1400 years enough for that?

Epoch,

The Bell Beaker culture began to arrive in Iberia c. 2500 BC. So, by the time the Romans arrived there, the languages which the former brought would have been diverging for over 2,000 years.

On the related note, it seems surprising for one Bronze Age group to have the need to wholescale borrow a basic counting system from another.

Alexander.

I suspect that IE might have expanded through Europe somewhat later, perhaps still unfolding during the second millenium BC. If so, the process went beyond certain lineages or farmer vs steppe models.

@Alberto

Also, on determining PIE roots. A system similar to what you propose was already used for reconstruction of PIE, with Sanskrit taking the position of Group B. Now, maybe that has the flaw that Anatolian wasn’t always included, which led to the distinction between early PIE and late PIE. But that doesn’t free the roots for your use of them, doubting their origin. If they weren’t PIE, they at least must have been *late* PIE for else there weren’t any cognates in Sanskrit.

@Rob

“On the related note, it seems surprising for one Bronze Age group to have the need to wholescale borrow a basic counting system from another.”

But not unique. See Chinese counting system.

Irrelevant but harmless side-note:

Why is there not an established discord server for anthrogenetics? These blogs certainly serve a more formal and organised purpose but the lack of instant messaging undeniably really slows general discussion down. This is obviously self-promotion (mods pls) but there’s nothing personal about this, no power trips or anything, I just think it would be good for everyone: I’ve recently created a discord server for people to talk about this kind of stuff more informally. Link here – https://discord.gg/QRbVFGF

No matter your opinion it’ll be essentially impossible to get banned unless you’re actually being disruptive (spamming etc.), so there won’t ever be scenarios like with certain other websites restricting discussion of “unpopular” ideas. The only other relevant caveat to this is that hypertribalistic behaviour would get labelled as disruptive and is bannable as it always ends up destroying valuable discussion: what I mean by this is the kind of things like Balkan flame wars polluting everything it touches. Otherwise, it’s a free speech anthrogenetics server and nothing besides, to complement the more formal and laid-out discussions on sites like this. Hopefully, that means maximum discussion!

@epoch

“In your explanation you state that this scenario requires 1400 year of isolation and inbreeding. But that is obviously not true, as the area where Iberian and Basque were spoken were pretty large, about half of Iberia plus Aquitaine.”

I have a hard time following you. If what you are proposing is that non-IE languages were widespread, then that’s the same thing I’m proposing.

If you could explain more clearly (to me and the other readers) who were (according to you) the IEs and who the non-IE during the Bronze Age in Iberia (and Western Europe as a whole), when and how did those IE pick up Iberian languages and how we ended up with the linguistic landscape that we know during the Iron Age, that would make it much easier to understand what you’re saying and agree or not.

“Also, on determining PIE roots. A system similar to what you propose was already used for reconstruction of PIE, with Sanskrit taking the position of Group B.”

What do you mean by “was already used“? That someone used it at some point but then it was ignored by the rest of the linguists? Or do you mean that this is the golden standard followed by all linguists for determining if a root is PIE or not, until today?

@Alexander

Why is there not an established discord server for anthrogenetics?

I wouldn’t have the time to keep up with those discussions, so I can’t refer people to go there. For me it’s easier and more useful to keep this more formal format here, but if others want to create and participate in those other ones, it’s fine for me if they create one and post a link to it here.

@Alberto

I propose what you consider unlikely, that BBC was originally IE speaking, picked up local non-IE languages that existed in Iberia and that the Celtic languages entered Iberia during the Iron Age. Your objection against is this:

” Some sub population could have adopted the local language for one reason or another. One problem though, is that after that, we need such population to keep that non-IE language for the subsequent ~1400 years in spite of them being surrounded by IE speakers (who in their surroundings would have spoken the same IE language and would have been able to communicate easily). This scenario requires a geographical (more likely) or some sort of ideological (less likely) isolation of the non-IE speaking population. ”

I consider that untrue because Olalde shows that two groups lived together for 6 centuries before the R1b group prevailed, so there is ample time for all kind of dynamics. At the point the R1b group on Iberian east coast prevailed they were speaking Iberian languages because they somehow switched language. That is a pretty large area, large enough to have enough critical mass to sustain itself. The IE substrate fits such a scenario neatly.

@epoch

Thanks for clarifying.

That’s not the scenario that i consider unlikely. What I consider unlikely is that Bell Beakers replaced non-IE languages across Iberia (and Western Europe) and that later (some 1500 years later) Iberian languages expanded from some unknown, small population.

What you are proposing (Bell Beakers adopting local languages in large areas of Iberia and at least SW France) cannot explain the presumed IE substrates seen in these areas.

@Alberto

To the best of my knowledge PIE reconstruction required a word or root to exist in Western IE languages and Sanskrit. That means that you can’t just throw away etymological explanations, since even if the method wasn’t perfect, it at least required existence of a root in a language that never set foot in Iberia.

You also may state that since so many roots exist etymologies may have a larger chance of being coincidentally right, but that is never enough to throw away 50% PIE etymologies.

In other word, to consider Alba a coincidental mismatch is special pleading.

@Alberto

“What you are proposing (Bell Beakers adopting local languages in large areas of Iberia and at least SW France) cannot explain the presumed IE substrates seen in these areas.”

Off course it can. Why not?

I think epoch raises a good point in that any number of language sweeps might have occurred after the initial expansion, with a Vasconic group replacing earlier Indo-European layers after R1b reached near-fixation frequencies in Iberia. Of course this might be said about any place and time where differentiated populations encountered each other. I guess that’s one of the limitations of ancient DNA.

What irks me most about the steppe hypothesis is the lack of earlier IE languages in the wider European region (not considering the Balto-Slavic area). Under the steppe hypothesis one would expect to find at least one highly differentiated survival like Albanian (which persisted in an area constantly inundated with invading tribes) in Western- and Northern Europe, but instead there are strange substrate phenomena like Insular Celtic, Lakelandic/Laplandic, Schrijver’s A2 etc. and the Iron Age IE languages. I guess one such candidate might be Elymian, but southern Italy isn’t really western in the genetic sense.

@epoch

To the best of my knowledge PIE reconstruction required a word or root to exist in Western IE languages and Sanskrit.

If that was a real standard it would be great, since that’s what I was proposing. But it’s not really what I generally see (for example, *gel-) , but maybe some linguist can confirm or deny that.

As for the substrates, they are more resilient than spoken languages (that’s the point of using them to try to figure out previously spoken languages in the areas). So if Indo-European speaking Bell Beakers adopted local languages, why would the largest part of the substrate become IE and remain so for thousands of years, when no one actually spoke that language there (except maybe part of the population during a short transitional period)?

What those substrates require is a longstanding presence of IE speakers in the area, with a short lived Iberian speaking presence.

@Alberto

>What those substrates require is a longstanding presence of IE speakers in the area, with a short lived Iberian speaking presence.

Aren’t the farmers the only group fulfilling that requirement? This would have to be qualified, of course, since there is a high likelihood of language shift with the strong introgression of WHG and male biased replacement. I find it unlikely that G2a Anatolians and I2a megalith builders for instance would have spoken related languages.

@Alberto

“As for the substrates, they are more resilient than spoken languages (that’s the point of using them to try to figure out previously spoken languages in the areas). So if Indo-European speaking Bell Beakers adopted local languages, why would the largest part of the substrate become IE and remain so for thousands of years, when no one actually spoke that language there (except maybe part of the population during a short transitional period)?”

Well, as you said yourself: The hydronyms and toponyms are more resillient than spoken languages. I don’t see a problem there. The picking up of languages wouldn’t have been an ad hoc process where the entire Iberian area switched all at once.

I have no idea what the dynamics were. But pre-steppe Chalcolithic Spain already became different from previous farmer cultures and the link below show that these cultures acquired a warrior culture with status burials. That means some incoming BBC groups could have taken over existing power structures in those 6 centuries.

https://rd.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10963-018-9114-2.pdf

Since Villar contends that old IE toponymy is more persistent in the south, remind me was this site tested yet?

https://bellbeakerblogger.blogspot.com/2018/05/a-prince-and-his-twenty-wives-garcia.html

I wonder if the big guy there has G2a, I2a or a stray steppe lineage. This seems to be the site where those Chalcolithic social changes are most evident.

@Marko

Aren’t the farmers the only group fulfilling that requirement?

Yes, I think that the only reasonable explanation for those substrates would be if the Early Neolithic Farmers brought Indo-European languages from Anatolia (as in Renfrew’s hypothesis). So if the latter turns out to be correct, then probably the substrates are correct too. Conversely, if the Anatolian Hypothesis turns out to be incorrect, the substrates are probably incorrect too (and this is the assumption I’ve gone for in the post).

Who knows, maybe as more data comes out we’ll have to revisit the Anatolian Hypothesis as the only viable option left. With the twist that the early IE languages of Europe went extinct and replaced later by others closer to the core area (which actually would be Northern Mesopotamia, rather than Anatolia itself).

But this is quite speculative right now. There are many problems for the Anatolian Hypothesis that would need to be addressed before we can consider it a serious contender again.

BTW, I don’t think we’ve seen DNA from that man yet. Given the date it’s not possible for him to be an R1b/Steppe guy though.

The dynamics in Iberia really are quite fascinating ; and definitely worth a closer look; in light of some suggestions above.

With regard to chronology; it appears that BB first “lands” in Meseta (and not the Tagus estuary; as has long been posited) c 2500 BC. They certainly appear amidst other groups; which themselves appear to have been quite diverse (even featuring the anticipated individuals with North African affinities). However, this doesn’t seem to have resulted in a fusion or free -for-all; but instead a brief coexistence (where the different groups used separate burial locations even within the one complex ); followed by the ascendency of one particular group. By 2200 Bc; the main chalcolithic groups in the south had all “collapsed”; and the new dominating horizon (El Argar) had no roots in the former; whether in site topography or burial styles. All earlier Los Millares sites show abandonment as do the earlier wealthy tholoi tombs (by 2400 BC). Again in the south it is the same group as those in the north which rose to dominance; as im sure all aware from the uniparental data

And whilst the odd non-L51 lineage hovers around until 2000 BC; the transition in Iberia; in terms of power structures; is eerily rapid and complete. The most economical explanation is that there would be no great incentive or opportunity to commit to language switching (but of course theoretically possible). This is not a case of Visigoths integrating, in some way or form, into local Iberian Romanitas.

Marko, the issues as I understand them with the Anatolian hypothesis are that many linguists have a problem with the slow rate of linguistic change implied by it. From a paleo-demographic and ‘culture-historical” perspective, too much happens between the arrival of early farmers from Anatolia until the attestation of IE groups; and it is difficult, for ex, to envision the obvious similarity between Balto-Slavic & indo-Iranian if they diverged in, say, 7000 or even 5000 BC.

In the East Balkans and parts of Anatolia there is in fact settlement discontinuity for up to 500 years after 42/4000 BC. So any scenario will have to take this into account.

At the same time, the scenario of multiple arrows emerging out of the steppe might require revision, because it seems that some of the movements are associated with offshoots where later attested languages are arguably non-IE (BBC) or became locally extinct (Afansievo).

@Marko, is the lack of earlier IE languages in the wider European region (not considering the Balto-Slavic area). what’s so odd about that?

The wider European region (and I would guess we mean Europe north of Balkan Mountains, given this blog) is a linguistic spread zone marked by either repeated and known radiations (Slavic / Germanic / Romance, possibly Celtic), or at least frequent contact preventing formation of divergent varieties (the ‘Celtic as developing through contact’ theory of Andrew Garrett).

If you had a topology like the Caucasus or Pyrenees, it might be odder. Mountainous topology preserves languages better than flatland (see PNG for another illustration), warm climates tend to preserve better than cooler (empirically – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278416598903282).

Analogous, within linguistics around Sino-Tibetan, there are arguments against Sino-Tibetan originating on the North China plain. But saying “But this massive Chinese Empire on the North China plain, today, only speaks one variety and many isolated peoples in the southwest hills speak very, very many” is not really one of them, alone! (There are known historical and geographic-demographic processes which make that a fairly bad piece of evidence).

@Matt

Disagree, a landscape like Fenno-Scandia is favorable for preservation, that’s why not-so-distant paleo-language layers are fairly obvious there. Sweden is flat, but peoples and languages don’t diffuse as readily through the northern forest as they would in Iberia for instance. Hence the dynamic seen in ancient DNA.

Germanic/Saami-Finnic/Baltic Y-DNA shows this as well, in that it is quite disjointed and marked by local founder effects, in contrast to Western European populations which were for the mostpart fathered by the L51 guy.

To use the examples of Germanic, Slavic & even Roman, they inform that these were demographic – migratory events (c.f. political-cultural for Roman along with native client management, re-settlement & colonization); and those languages are indeed quite differentiated within the I.E. tree.

Whilst Celtic is just on the cusp of proto-history, that ancient authors were noting their movements around Europe, and there is an expansion of ”Celtic material culture” speaks volumes. I think recent scholars have been a little too deconstructionist in their approach to such questions, and now might have to back-peddle a bit. The expansion of classic Celtic might have had a dialect levelling effect in some areas, whilst representing a wholly novel introduction of I.E. in others. Even with fine-grained correlative archaeo-genetic analysis, it might not be entirely clear.

I suppose considered in isolation the language argument isn’t very strong and Matt was right raise those criticisms.

I should have expressed myself clearer in that it is the fact that where the Iron Age languages (Celtic, para-Celtic, Germanic) one finds non-Indo-European languages (Tartessian, Aquitanian, Iberian, Rhaetic, Etruscan) and not differentiated IE survivals as one would expect if BB spread IE already in the EBA. It would require a highly selective replacement of old IE languages.

@Marko

Yes, the selective replacement of Bell Beaker languages in R1b heavy areas of Western Europe, with not even one surviving into the Iron Age sounds strange enough to consider it highly unlikely that the pre-Celtic Western European linguistic landscape was large IE (of unknown branch).

It’s much easier to imagine that it was largely Ibero-vasconic, and that Celtic expansions replaced large areas were those languages were spoken, but still in other areas were not replaced.

@Alberto

“Yes, the selective replacement of Bell Beaker languages in R1b heavy areas of Western Europe, with not even one surviving into the Iron Age sounds strange enough to consider it highly unlikely that the pre-Celtic Western European linguistic landscape was large IE (of unknown branch).”

There is at least one theory that proposes a non-Celtic, Non-Germanic Indo-European substrate in the North West of Europe: the Northwestblock Theory. It is based, in part, on hydronyms and toponyms.

“It’s much easier to imagine that it was largely Ibero-vasconic, and that Celtic expansions replaced large areas were those languages were spoken, but still in other areas were not replaced.”

Why much easier? The Vasconic substrate theory by Theo Vennemann has been rejected by most linguists because Venneman compared European hydronyms to *modern* Basque, which skews the results. To propose a NW Block actually makes pretty much sense.

Yes I think its difficult to argue that Vasconic goes back to Solutreans, or that Megalithic Europe spake Semitic. However, Koch, Schriver have also pointed to a Vasconic substrate in Celtic. It is also interesting that linguists generally view Celtic & Germanic to be distinctive, apart from some obvious recent loans, despite their geographic proximity. It suggests that they have had quite different formations, population wise. But I dont know any specifics of substrate study to comment on whether it is correct or not.

One of the interesting things about Celtic in light of the ancient DNA evidence is the increasing non-IEness as one approaches the North-West European fringe. A good summary can be found in Matasović, Ranko, “The substratum in Insular Celtic”. As for the continental Celtic languages and the supposed Vasconic substrate, is there any recent work on this (apart from Koch)?

Germanic is more complicated. The agricultural substrate should be investigated (and some of it is quite puzzling, for instance why would the Germanics have borrowed words for bull, cow, goat etc.?). More esoterically, Shrijver’s A2, “the language of geminates”, which doesn’t affect Proto-Germanic but its offspring. Finally I’d also like to see a discussion of the archaic Germanic loans in Proto-Albanian that Vladimir Orel lists in his book.

Marko: “Under the steppe hypothesis one would expect to find at least one highly differentiated survival like Albanian (which persisted in an area constantly inundated with invading tribes) in Western- and Northern Europe”

Albanian itself might have ended up fully Romanized in the long-run if it weren’t for the Avaro-Slavic disruption of the imperial system in the Balkans though. It already shows very pervasive Romance influence, of both the Dalmatian and Eastern Romance varieties, after all. The early Albanian-speaking population that emerges after all these events is quite small and only expands considerably towards late medieval times. That kind of linguistic survival seems like the result of a streak of pretty good luck (and partially likely helped due to mountainous landscapes in central-northern Albania and thereabouts) and to generally be more the exception than the rule in Europe. I’m not sure we should necessarily expect that to be the case a priori then. Had things turned out a bit differently, linguists might be attempting to reconstruct more hypothetical substrates (akin to nordwestblock, alpine etc. in western Europe) than studying a living language. Who knows? The general lack of early writing in most of Europe obviously doesn’t help either.

Are varieties like the various poorly attested western European ones that linguists aren’t able to neatly categorize as either Italic or Celtic a really different story to the extinct Balkan branches anyway?

Btw, in the most recent G25 spreadsheet, I notice an interesting newly added sample “TZA_Zanzibar_First_Millenium_I0588” (supposedly from the Skoglund et al. https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(17)31008-5 but it doesn’t seem to be in it) that’s Iberian-like and is dated c. 800 AD in the Harvard database. Could there be Iberian individuals in Zanzibar that early (say, movement within the Islamic world) or is it more likely that it’s misdated?

2713/5000

I see a problem in these debates that I am surprised. It is being taken for granted that the falsifiable hypothesis (because it is only that) that the Iberian numeration is virtually identical to the Basque or Basque one is already a theory or a proven fact.

Apparently no one is considering that it could simply be a mere forced construct. Analyzing the same in depth, it is easily discovered that everything is merely speculative. There are very few elements that actually lead to think that the sequences, which have been artificially biased (without in some cases respecting the divisions themselves using points in the same Iberian texts) are really words, in this case, lexemes for numerals. In fact, we reach the absurdity of assuming as if it were something natural that in texts where the Iberians use symbols for numerals (vertical bars), which is what they always do, they also write – supposedly – the same numerals in their form lexical That contravenes the principle of economy.

But most importantly, a recent study has shown that the Iberian letters used as acrophones in the two Iberian dice found to date correspond to the acrophones (principle of acrophony) of the main sounds of the words or used for numerals in Altaic -Turkic languages, but not with Basque or Indo-European or Afrasian numerals.