Thanks to the preprint discussed in the previous post, we now have a good amount of aDNA from around the Caucasus that can help us understand what was going on in this key region. The answers are still not clear, but we can take a look at what we have and see what we have learned and what is yet needed to fill in the gaps.

From the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic

The Neolithic in the South Caucasus has been dated to start around 6000 BCE, though recent finds might push that date back at least 1000 years to a much more reasonable 7000 BCE (probably earlier). Unfortunately we don’t have any Neolithic DNA from the area, though we do have UP and Mesolithic samples and other Neolithic samples from surroundings. Overall, we can expect that the Early Neolithic Shulaveri-Shumu Culture should be somewhere intermediate between CHG and ANF. I really don’t have a clear idea of what the Late Neolithic Sioni Culture (from c. 5000 BCE) represents. Maybe some migration related to the Halaf Culture, or just a different phase in the Neolithic development. Genetically we shouldn’t expect a big change, probably just a more complex mixing of different people, including some Levant and West Iran.

The first Neolithic samples we have are actually from the Northern Caucasus. A Meshoko-related site called Unakozovskaya, a bit to the south of Maikop. The three individuals are from around 4500 BCE, and are family related as shown by their common mtDNA R1a. The Y-DNA of the two males are J and J2a respectively.

We can assume that they basically represent a migration from the Shulaveri-Shomu Culture to the north of the Great Caucasus mountains. They are autosomally modelled as some 50/50 CHG/Anatolia_ChL, while Anatolia_ChL itself might be around 70/30 ANF/CHG. So till here everything looks as expected.

The significant change in the South Caucasus comes at around 4200 BCE. Traditionally linked to the Uruk expansion, this has been debunked by more careful analysis of the archaeological data suggesting an origin from the East¹. This is confirmed by the Armenia_ChL samples, which point to anywhere but the south, and which are some of the most intriguing ones we have so far.

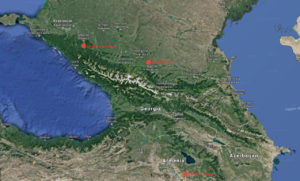

These Chalcolithic samples from Armenia are dated to around 4300-4000 BCE and come from the Areni-1 Cave (see map below).

The genetic structure of these samples is quite difficult to assess. On one hand, they do show an Iran/SC Asian signal, together with their Y-DNA L1a. On the other hand, they also show steppe admixture (rather than EHG, since now we know that, at least at this time, at this time there were no EHG in the North Caucasus steppe, but rather a population that was intermediate between CHG and EHG, and basically directly ancestral to Yamnaya. This admixture in the samples is a bit surprising, if we assume that these Armenian samples represent newcomers from the east or south east, and they’re still quite south of the steppe. By contrary, the slightly older samples from near Maykop don’t show this admixture. It probably occurred through the Caspian rather than the Black Sea coast.

But even more surprising is the shift towards the North West that these samples show. Something like Balkans LN admixture. Given that neither of the samples from North of the Caucasus mountains show this admixture, it seems unlikely that it arrived through the northern Black Sea route. But we have no evidence either of this admixture coming through Anatolia. So at this point is difficult to say if this is really admixture from Europe or something else. We’ll have to wait for further samples to clarify this.

And then the Maykop Culture appeared in the North Caucasus. One of the most important Early Bronze Age cultures, its origin has been rather obscure debated for a long time. It’s only in the last few years when archaeology started to reveal some more clear connections to it from other cultures and the works of Mariya Ivanova were able to propose a well substantiated hypothesis about its origin¹, linking it to the Iranian plateau and South Central Asia.

Genetically the Maykop samples look to descend from the Armenia_ChL population that arrived to the South Caucasus around 4200 BCE and then moved to the North Caucasus around 3900-3800 BCE. Unfortunately we hardly have any Y-DNA from Maykop’s early period (a single possible J, but marked as contaminated), but the 3 Late Maykop samples with Y-DNA belong to L, like the Armenia_ChL ones.

Archaeologically, I’ll just add a few quotes from Ivanova 2013² to complement the previous reference. Speaking about the appearance in the North Caucasus of luxury items (gold, silver, carnelian, turquoise, lapis lazuli), she mentions the possible route:

The distribution of highly prized luxury goods, especially ornamental stones, hints at the westward extension of this central Asian network of the Namazga II-III period into north and west Iran.

And making a case for the associated distribution of early tumuli:

The plain of Lake Urmia may indeed have been the frontier region where the societies of Iran and the Caucasus came into contact. Near the southeast corner of Lake Urmia, excavations took place in a cemetery of eleven tumuli at the site of Sé Girdan (Muscarella 2003, 126 f.). The mounds were encircled with revetments of rubble stone and contained one grave each, often covered by a rock pile. The well-built stone chamber tombs with pebble floors and timber roofs contained ochre-coloured skeletons lying on their right side with legs drawn up and hands in front of the face. Grave goods included numerous tiny beads of faience, gold, and carnelian; a stone scepter with a feline-head shaped end; a silver cup; flat axes and pick axes of arsenical copper (Muscarella 1969, 1971) (Fig. 4.22). Muscarella (2003, 125) concurred that the tumuli represent “a north-western Iranian manifestation of the North Caucasian, Maikop, Early Bronze Age culture”. However, animal-headed stone scepters and long axes of the type represented at Se Girdan are unknown from the north Caucasus, while pickaxes are extremely rare among the Maikop period finds.

Series of burial mounds in the southeast Caucasus provide better parallels for the tumuli in the plain of Lake Urmia.

And here she describes de Tumulus 1 at Telmankend, the tumuli from Soyuq Bulaq and a partly damaged tumulus near Kavtiskhevi in central Georgia.

The similarities of these tumuli with the burial monuments of the north Caucasus are unmistakable: earth mounds with encircling rubble stone revetments, stone heaps over the tomb, tomb chambers (among them also very large square chambers with stone-laid walls and pebble floors), red pigment, and the postures of the body are common features in both regions.

The geographic distribution of these characteristic tumuli seems to mark a route from northwest Iran along the valley of the Kura to the passes of the central Caucasus. Researchers regard sites like Sé Girdan as unusual monuments, which emerged under influence of or even through the direct migration of north Caucasian communities (Muscarella 2003, 125; Korenevskij 2004, 76, note 2; Kohl 2007, 85). This view appears feasible if such sites are viewed in isolation. Considered in the historical context outlined previously, however, the available evidence begins to reveal a new and meaningful pattern. Like several other innovations presented previously, the complex of peculiar funerary practices most probably spread from northwest Iran and the lowland areas of the southwest Caspian northwards along the valley of Kura, and reached the northern slopes of the Caucasus around the second quarter-middle of the fourth millennium BC. Thus, the funerary evidence adds further credibility to the hypothesis that the foreign elements in the north Caucasus originated from the Iranian plateau and its borderlands, and not from Greater Mesopotamia or the Anatolian highland, two regions which lie far outside the area of distribution of early tumuli.

Indeed David Anthony³ mentions the Sé Girdan tumuli and their remarkable similarity to the Novosvobodnaya-Klady types, and concludes:

The Sé Girdan kurgans could represent the migration southward of a Klady-type chief, perhaps to eliminate troublesome local middlemen.

However, it seems that Ivanova’s suggestion is better backed up by recent archaeology and (pending further details) the genetic evidence.

Regarding the relationship between Maikop and Novosvovodnaya, there is a relatively small but significant genetic difference between the two. The latter seems to represent a second wave of migration, this one more specifically linked to NW Iran, rather than East Iran/SC Asia. For example, in Supp. Table 9, when modelled as 3-way mixture of CHG, Anatolia_ChL and EHG:

Maykop: CHG 27.5%, Anatolia_ChL 69.7%, EHG 2.8%

Novosvobodnaya: CHG 43.8%, Anatolia_ChL 61.5%, EHG -5.3%

Yes, that’s a negative value for EHG in Novosvobodnaya. Conversely, in Supp. Table 10:

Maykop: CHG 31.3%, Anatolia_ChL 77.5%, Iran_ChL -8.8%

Novosvobodnaya: CHG 11.3% Anatolia_ChL 51.2%, Iran_ChL 37.4%

This time Maykop having a negative value for Iran_ChL while Novosvobodnaya takes a good amount of it.

The genetic pattern is more or less mirrored by the contemporary cultures south of the Caucasus, where there is a shift between Armenia_ChL and Armenia_EBA (Kura-Araxes) towards Iran_ChL. In fact the new Kura-Araxes samples from this paper also behave like Novosvobodnaya in these models.

The other difference is in the Y-Chromosome, with Novosvobodnaya having two J2a1 samples and one G2a2a.

Archaeologically, I think the main difference is in the increase in metal weapons found in Novosvobodnaya burials, but the details are not to clear to me, so I’ll leave it there for now.

NOTES:

- Ivanova, M. 2012, Kaukasus und Orient: Die Entstehung des „Maikop-Phänomens“ im 4. Jt. v. Chr.

- Ivanova, M. 2013, The Black Sea and the Early Civilizations of Europe, the Near East and Asia

- Anthony, D. 2007, The horse, the wheel, the language

“However, animal-headed stone scepters and long axes of the type represented at Se Girdan are unknown from the north Caucasus”

They are very, very well known in Khvalynsk and Suvorovo, though. As well as in the Leyla-Tepe related Soyuq Bulaq kurgans. If anything, the trail is southward.

@epoch 2018

The question here is if all those cultural traits went from the North Caucasus (Maykop/Novosvobodnaya) to the South Caucasus and beyond (like proposed by earlier researchers) or if it was the other way around (as proposed by Mariya Ivanova). Khvalynsk and Suvorovo are not relevant in this question, since they lack most of the features we’re talking about. Not to mention that ancient DNA does not support such scenario either.

@ Alberto

“The first Neolithic samples we have are actually from the Northern Caucasus. A Meshoko-related site called Unakozovskaya, a bit to the south of Maikop. The three individuals are from around 4500 BCE, and are family related as shown by their common mtDNA R1a. The Y-DNA of the two males are J and J2a respectively.”

-> I know you realise, but these are “Eneolithic’ or ‘Chalcolithic’ samples, not really ‘Neolithic propper’.

In fact, the Neolithic period (7/6000 BC — 50/4500 BC is still poorly known in the North Caucasus). Maybe a cave site or two ?

“We can assume that they basically represent a migration from the Shulaveri-Shomu Culture to the north of the Great Caucasus mountains. They are autosomally modelled as some 50/50 CHG/Anatolia_ChL, while Anatolia_ChL itself might be around 70/30 ANF/CHG. So till here everything looks as expected”

-> So if Meshoko are actually Chalcolithic immigrants from E Anatolia, they could be ‘Uruk migrants”, or ‘on the northern periphery of Uruk, migrants”, and not S/S people.

@Alberto

“Khvalynsk and Suvorovo are not relevant in this question, since they lack most of the features we’re talking about. ”

Suvorovo has Kurgans, and the burials that Ivanova describes are reflected in eneolithic burials in the North Pontic which also show stone heaps and stone encirclement.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/mom_2259-4884_2012_act_58_1_3470

“Not to mention that ancient DNA does not support such scenario either.”

We don’t have any DNA of Sé Girdan or Soyuq Bulaq. The only thing we do know is that the Caucasus paper states that it can’t model the Caucasus Maikop population without a small (4%) EHG admixture.

@Robert

Yes, by 4500 BCE those would be Chalcolithic samples. I was trying to figure out what was the difference between Shulaveri-Shomu and Sioni cultures in the South Caucasus, but to be honest the whole concept of Sioni culture seems quite vague to me. Maybe indeed that was an Uruk-related migration and these Meshoko-related samples could come from that Uruk-related migration. I don’t really know. Olympus Mons, who has spent a good amount of time looking at S-S and Meshoko thinks they are related, so I went with that assumption.

@epoch 2018

The problem is that Soyuq Bulaq predates Maykop, so it’s difficult to argue that it derives from it.

I’m not sure where you want to get to about Suvorovo (in Bulgaria) or the North Pontic steppe. Are you suggesting that Soyuq Bulaq were migrants from those areas?

Soyuq Bulaq is, as I understood it, roughly dated to early IVth millenium BC. The link with Suvorovo (and Maikop, btw) is that all eneolithic groups on the steppe had burials with zoomorphic scepters. Along the Lower Volga, the Dniepr, the Don, the Dniestr. It’s a pan-steppe cultural trait. Suvorovo is considered a steppe incursion into the Balkans.

So basically an eneolithic steppe intrusion could be the explanation for Soyuq Bulaq. Leyla Tepe mostly buried in jars.

It’s in here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286182086_Late_Chalcolithic_kurgans_in_Transcaucasia_The_cemetery_of_Soyuq_Bulaq_Azerbaijan

Two calibrated C14 analysis confirm these dates:

Kurgan 1: (UB-7609) 3951-3759 (2)

Kurgan 4: (UB-7613) 3768-3644 (2) et 3710-3652

Looks contemporaneous to Maikop.

@ epoch

“Suvorovo is considered a steppe incursion into the Balkans.”

That’s not exactly true , it certainly doesn’t seem to be the reading of specialists from the region , although such a theory is passed around in the blogosphere

To understand what suvorovo means requires a careful understand of chronology and the symbolic interchange which

occurred in the region.

Same thing goes for understanding the relation between the early, Suvorovo horizon, cromlechs / Kurgans and later (post-4000 BC) kurgans. When done, a very different reading of the archeogenetic record emerges.

@Robert

We have two samples from Mathieson that show Steppe admixture. Smyadovo (I2181) and Varna (ANI163). All other Varna samples show none and all other Smyadovo show no steppe admixture as well, so this means we see the arrival of steppe people.

So in the area, and around the time we see Steppe incursion.

While this is not conclusive evidence I think it gives the theory of people like Anthony that point to Suvorovo as an incursive culture with roots in the steppe credit.

@epoch 2018

Yes, I know the paper. Gold, silver, carnelian, lapis lazuli, arsenical copper dagger and awl, the pottery… And we have the Maykop DNA too. I find it a bit bizarre to suggest that this represents a migration from the steppe.

@Alberto

How is that bizarre? Bulgarian Yamnaya – confirmed steppe ancestry! – burials are stacked with local pottery.

Why should we reduce history only to one-way incursion of nomads from THEIR home area?

I googled with ”zoomorphic scepters” and found this:

https://books.google.fi/books?id=pA1-3KfkpuwC&pg=PA136&lpg=PA136&dq=%22zoomorphic+scepters%22&source=bl&ots=hUv4mUGF83&sig=29p0Gzwwxcm1Q2iezwE9h1itNqA&hl=fi&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj9y_fU0eLbAhWhJJoKHcYnD_4Q6AEIJTAA#v=onepage&q=%22zoomorphic%20scepters%22&f=false

”Consideration of the abstract and animal-headed stone scepters is instructive in this respect, particularly because some scholars have used them to document the early presence of domesticated horses. … The zoomorphic scepters occur with greater frequency in the Balkans and western Ukraine than farther east, a pattern that is reversed for the abstract scepters. … Occam’s razor need sharpening. A more parsimonius explanation views them as evidence for the very occasional exchange of luxury exotica and the gradual emergence of local elites who accumulated such symbolic goods as they gained power and prestige. The same pattern applies to the general distribution of metals throughout the Carpatho-Balkan Metallurgical province: their basic falloff west to east from the metal-producing and metal-working areas of the Balkans to their more sporadic acquisition farther east.”

I agree with Rassamakin’s conclusion: ”The early Eneolithic saw not warlike migrations of steppe peoples – a first kurgan wave – from the Volga or Caspian region, but rather the emergence of a mutually beneficial system of exchange between the steppe populations and the production centres of the agricultural world… The steppe world now emerges as a distinct yet well-integrated part of the prestige-trade network that existed in Southeast Europe.”

On a different note, the language can change even without a genetic change and genetically similar people can speak different languages. IMO, language change is often related to a interaction between cultures in which less developed people adopt/imitate the language of the more developed culture, and while they do so, a new language emerges that contains elements from both and the basic structure determines to which language family this new language belongs.

@epoch

Yamnaya_Bulgaria was archaeologically defined as Yamnaya for a reason. If there was one intrusive element it’s not enough to change it. And ancient DNA has confirmed that this was related to Yamnaya.

Maykop and Leila tepe cultures are not defined as steppe Eneolithic. They are much more advanced in every way to anything you can find in the steppe at that time. Once again, ancient DNA has confirmed that they have nothing to do with the steppe (Maykop, for now, but also Novosvobodnaya, Kura Araxes, Chalcolithic NW Iran…)

I don’t understand why you insist in something that makes no sense. Is it the stone scepter with an animal hear that seals the deal for you? The one found at Soyuq Bulaq is quite similar to the one at Sé Girdan with a feline head. Have you noticed a big similarity between them and any from the steppe from the 5th mill. BCE?

And why do you consider the intrusive pottery in Yamnaya_Bulgaria as intrusive, but don’t apply the same principle to the zoomorphic scepter even if you had any proof of it being intrusive?

The evidence from every point of view is overwhelming. If you still want to cherry pick what suits your preferences, fine. You can write your own blog with your opinions, or share them at Eurogenes or Anthrogenica where many people might be interested in them and will agree with you. Here I hoped I wouldn’t have to deal with these debates anymore.

That said, if you want to debate realistic and reasonable things for a change, you’re welcome, as anyone else.

@ epoch

“We have two samples from Mathieson that show Steppe admixture. Smyadovo (I2181) and Varna (ANI163). All other Varna samples show none and all other Smyadovo show no steppe admixture as well, so this means we see the arrival of steppe people.

So in the area, and around the time we see Steppe incursion.”

What the data suggests to me is ANI163 – a female of Ukrainian ancestry was buried in local cemetery in a respected fashion.

It takes some imaginative fortitude to see that as an “incursion“ (def: “an invasion or attack, especially a sudden or brief one.”)

Similarly the Smyadovo chap, and others like him, who belongs to I2a2a1b – found throughout the Romania , Hungary , Serbia , Bulgaria region long before Yamnaya, begin to show increasing steppe admixture with Time. Just like your discussion with Alberto above, you seem to be conflating possessing steppe admixture with something originating a priori in the steppe and the diluting down instead of considering the converse possibility. it would also help to understand how the Yamnaya horizon actually came about.

Lets also not forget that even before the varna steppe lady appeared, the other way- in the steppe, we see Neolithic EEF admixture in Ukraine

So we’re actually seeing intermixuture and acculturation across the frontier in a nuanced way, which begs the question – who’s the patron and who’s the client ?

Future data might show that those Suvoro chiefs were local foragers from the lepenski Vir/ Bug -Dniester zone , not “ galloping nomads” from afar. This detailed analysis shows a different picture to the narrative one encounters on blogs and even amongst run -of -the- mill academics

Thank you vey much for the post Alberto.

certain ideas were pervasive and may have spread with indirect or minimal contact. Zoomorphic scepters are famous in Egypt going back to the predynastic era and are a sign of royalty. There is some similarity between pyramids and kurgans.

@Rob

The Smyadovo outlier was assigned Y-DNA “R”.

@ Epoch

Oh you’re talking about Outlier, yes you’re right, he’s simply “R” (probably R1b-V88 like the others?) Looking at the suppl – he’s buried wiht the rest of the people, in a typical ‘Neolithic’ pose (side-crouched position). Doesn;t seem like a predatory raider to me

Yet there’s also an R1b1 there in Chalcolithic that isn’t an ‘outlier’, and of course also in Varna.

It’s the Bronze Age ones which are I2a2 in Bulgaria and also have steppe.

It just confirms the porous border and variable individual mobilist – some R1s had steppe others did not, same with I2a2.

Thus, if the “collapse” of Varna was due to steppe-rich incursions of R1 people, why are all the Bronze Age ones to date I2a2 ? Indeed when the varna culture collapsed, so too did Suvorovo. It means there’s more to the story than meets the eye

This brings us back to the Meshoko fortresses. They appear at that very same time (c. 42/4000 BC). Coincidence ?

@Kristiina

Your point here about the horse-headed sceptres is very important

Some have have claimed that they’re markers of “steppe-invaders” – kind of like bread crumbs left for us modern scholars to notice .

The fact that the more formal ones cluster in the Balkans and the more abstract (?copies) in the Volga doesn’t quite sit well with that.

Also important is the fact that these sceptres are found in ‘normal’ Balkan contexts – in domestic spaces of local Balkan cultures like ‘Karanovo’ and not in destruction horizons or anything culturally attributable to ‘nomads’.. It’s all about context

Alberto. Thanks for reference.

I detail my view here, including what sioni could be.

https://r1b2westerneurope.blogs.sapo.pt/from-the-ubaid-and-kura-araxes-8426

Sioni is remnant of something. Not new.

Most people forget that besides than shulaveri, in western Georgia there were the pasturi, anasueli, etc. which of course admix with with shulaveri but should be a bit different. These always should show a more older component than the shulaveri it self. More basal CHG maybe.

When Shulaveri disappeared that western component took their place, hence known as Sioni. They became later part of kura araxes in “oposition” to more uruk/leilatepe people.

I think it should be something like this.

This is important. Rob you know how many times I quoted Manzura!!

http://www.academia.edu/35556491/The…_to_Eneolithic

Quote:

We have fixed very important changes in the burial rites of the steppe population. Stretched Neolithic inhumations were replaced by flexed skeletons and some graves with groups of stones above them or burials in stone boxes. I. Manzura was right when he connected those changes with western infuence.The people of new Sredniy Stog culture,which was formed on the basis of the local Neolithic, could contrast new burial rites with old traditions (Manzura 1997). It is possible to assume that those radical changes in the burial rite, which was a part of conservative religious sphere, were connected with changes in cults. The most important innovation was the appearance of the metal working borrowed from the Balkan region. Metal working in the Prehistory was closed connected with the religious sphere of life and adoption of new technology in everyday life had to be accompanied by adoption of new cults. We can observe the consequences as changes in the burial rites. The time of formation of the Sredniy Stog culture was synchronous with the Hamangia culture and exactly its influence caused the transformation of the steppe burial rite, because flexed skeletons and using of stones were typical for this culture (Todorova 2002a, 35–

The transition from the Neolithic to Eneolithic in the Eastern European steppe was connected with the inten-sive contacts of people of the Azov-Dnieper, Low Don, Pricaspiy, Samara, Orlovka and Sredniy Stog cultures with the Balkan population and first with the Hamangia culture. The results of these contacts were some im

– ports: adornments from copper, cornelian, marine shells and pots in the steppe sites and plates from the bone

and nacre, pendants from teeth of red deer in the Hamangia graves. The Hamangia infuence in the burial rites

of the steppe population was very important and caused to use stone in graves and above them, pits with alcove,

new adornments of burial clothes. The strongest impact we have fixed for the population in northern area of the

Sea of Azov, where the radical changes in the burial rite and the formation of a new Sredniy Stog culture took place. It was connected with the adoption of new religious element.

One interesting place I’d like to see ancient DNA is Ikiztepe, especially from around the middle of the 5th mill.

It could give us some clue about the origin of “European-like” admixture in Armenia_ChL. Maritime contacts with the west Black Sea coast are quite likely. And it might have been more than just trade if we give any importance to the funerary practice of burying the dead in extended supine position at Ikiztepe, in contrast to the rest of Anatolia where flexed on the side was the norm. The closest analogies come from Varna or Hamangia cultures in the East Balkans.

@ Alberto

“It could give us some clue about the origin of “European-like” admixture in Armenia_ChL. Maritime contacts with the west Black Sea coast are quite likely. And it might have been more than just trade if we give any importance to the funerary practice of burying the dead in extended supine position at Ikiztepe, in contrast to the rest of Anatolia where flexed on the side was the norm. The closest analogies come from Varna or Hamangia cultures in the East Balkans.”

Taken as a whole, they’re both significant. Prior to this, Anatolia had intra-mural cemeteries, but then switched to large extramural cemeteries. Whether extended inhumation or flexed, the influences speak of expansion from the lower Danube, where the earliest such cemeteries emerge. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/radiocarbon/article/emergence-of-extramural-cemeteries-in-neolithic-southeast-europe-a-formally-modeled-chronology-for-cernica-romania/08AA4989EF02D322FCF9961719D71AAB

Concerning Sioni

Overall yes they are archaic as OM said but I don’t think they are from west Georgia.

They are the resurgence of archaic CHG which didn’t vanish with the arrival of Neolithic farmers. They were living in mountains, forests and gradually overrun shulaverians and probably mixed with them.