Celtic

A few months after I published the article “Origins and spread of Indo-European languages: an alternative view“, a new study was published (still as a preprint, now at version 3) about the spread of Celtic languages that is the most important one on the subject published up to this date:

Tracing the Spread of Celtic Languages using Ancient Genomics

Hugh McColl, Guus Kroonen, Thomaz Pinotti, John Koch, Johan Ling, Jean-Paul Demoule, Kristian Kristiansen, Martin Sikora, Eske Willerslev

bioRxiv (original publishing date: 2025.02.28) current version 2025.05.08; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.28.640770

The study tries to answer the question about the spread of Celtic languages comparing 3 competing hypotheses:

“(1) a Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age spread from Central Europe associated with the Hallstatt and La Tène Cultures; (2) a Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age spread along the Atlantic seaboard linked to the Bell Beaker Culture; and (3) a Bronze Age spread from France, Iberia or Northern Italy.“

The first one is the classical and most accepted one for many decades already, but the second one became popular in the recent years with the findings from ancient DNA studies showing that the Bell Beaker Culture was associated with a large migration from the steppe. The problem with this latter hypothesis is, as noted in the paper:

“Over a thousand years separate the presumed arrival of Indo-European dialects to Western Europe (c. 4300 BP) and the formation of Proto-Celtic (c. 3200 BP).”

And continues:

“However, how the population structure changed over this period remains unclear. To be able to evaluate the three hypotheses on Celtic origins, it is therefore first necessary to understand the demographic processes affecting Bell Beaker-derived groups of the second millennium.”

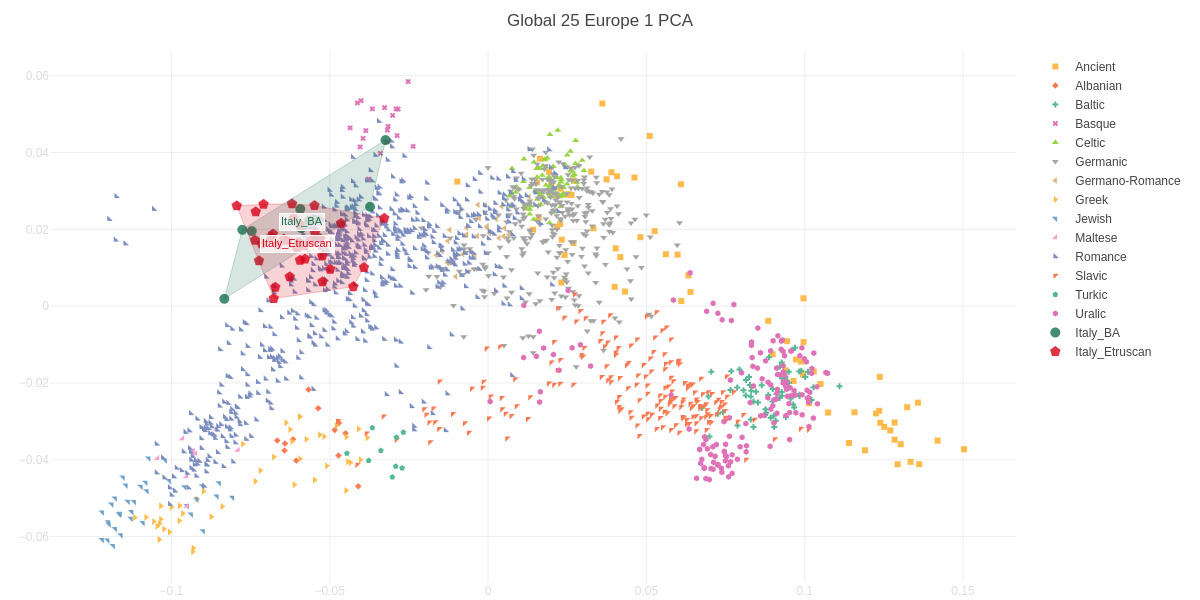

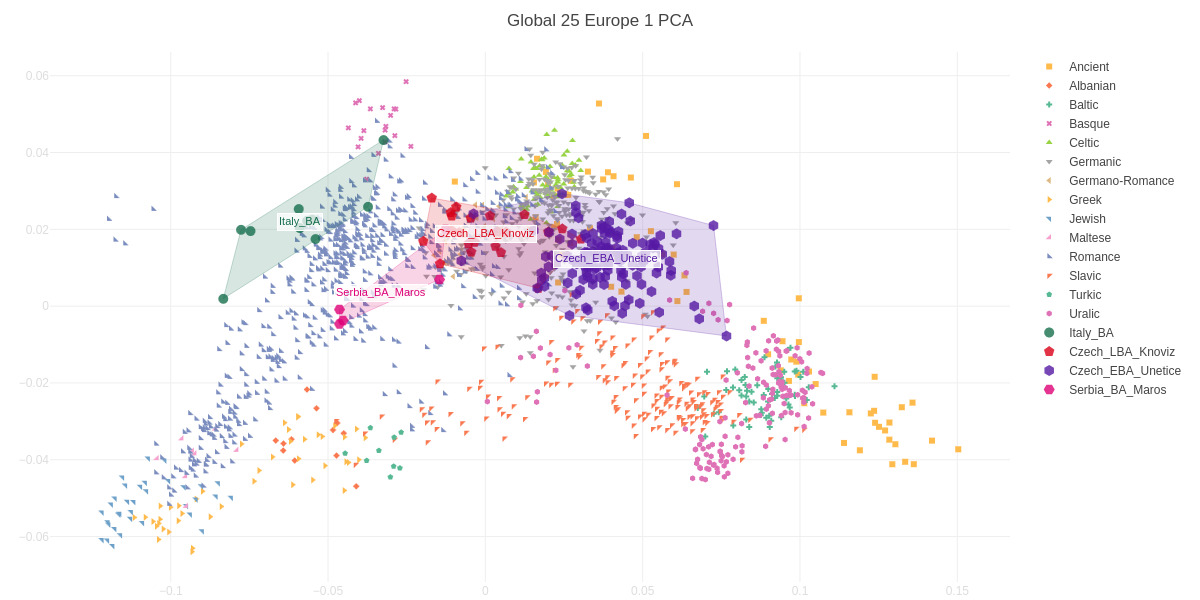

In my original article mentioned above I had already noticed a genetic shift in a transect of the samples from Czech Republic available that pointed to a migration from the Northern Balkans to Central Europe coinciding with the shift from the Únětice culture to the Tumulus culture ca. 1500 BC (and persisting in subsequent cultures from the region like the Knoviz and the Hallstatt cultures). The new study picks up on that same signal and takes it to a whole new level by tracing it throughout the rest of Central and Western Europe. The following PCA generated using Vahaduo’s Global 25 views shows that shift:

Here’s what the study says about it (emphasis mine, here and thereafter):

Further east, in the Czech Republic, we see the increase of Italian Neolithic-related and Bronze Age Anatolian-related ancestry between 3200 and 2800 BP (Fig. 3). We also note that we detect no evidence of French/Iberian Neolithic ancestry. By splitting further into the cultural phases for the region, we find that this ancestry profile in the Czech Republic occurred by 3300 BP, in individuals associated with the Tumulus Culture and continuing into the Knovíz and Hallstatt periods (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Moving further west, to France, it says:

In France, we see a similar transition (Fig. 3). During the Early and Middle Bronze Age, more local French/Iberian- than Italian Neolithic-related ancestry tends to be present. By the Iron Age, the relative proportions have swapped, so Italian Neolithic-related ancestry is the highest, accompanied by Bronze Age Anatolian ancestry.

And about England:

For England, we find a series of transitions in the prominent Farmer ancestries present for each time slice (Fig. 3). Initially, between 4800 and 4000 BP, we find that individuals are modelled with a high proportion of Bell Beaker-related ancestry, and the tendency to have a slightly higher proportion of local British-Irish Isles Neolithic ancestry, relative to the other Neolithic-related ancestries. By 4000–3200 BP, the highest Farmer-related ancestry is French/Iberian Neolithic-related rather than the local Neolithic ancestry, consistent with recent studies suggesting migrations from the mainland . This migration, specifically the Iberian connection, is further supported by evidence that the UK received copper from Iberia during this phase (3350/3250–750 BP). However, in the Late Bronze Age, we see a shift, in which the proportion of Italian Neolithic ancestry has increased to similar proportions to that of French/Iberian Neolithic. In the Iron Age, similar patterns are seen, with the additional appearance of Bronze Age Anatolian-related ancestry.

Continuing towards an interpretation of the results, it goes on by saying:

Consistent with the results found from using the Farmer-related ancestries as a proxy, we find Bronze Age French/Iberian ancestry appearing in England during the Middle Bronze Age, and the Hungarian/Serbian Bronze Age reaching widespread distributions during the Iron Age (Fig. 4). In the Czech Republic, we find almost all individuals being modelled with a large proportion of Hungarian/Serbian ancestry during the Late Bronze Age.

[…]

The results here indicate a migration from Eastern Central Europe, occurring between 3200–2800 BP. The genetic impacts diminish the further west that they are detected, but can be measured as far west as Iberia and the British Isles. The Knovíz-related source that models this migration is found in the Czech Republic from 3300 BP. However, we note that this population is distinct from the earlier Únětice people from this region before 3800 BP (Supplementary Note S1; Extended Data Fig. 1) and has links further south and east, evident from the appearance of Italian Neolithic Farmer-related and Bronze Age Hungary/Serbia-related ancestry. Thus, we observe that the population of the Únětice Culture does not significantly contribute to the ancestry of the successive Hallstatt Culture.

Which brings them to their conclusion already expressed in the abstract:

In line with the theory that Celtic spread from Central Europe during the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age, we find Urnfield-related ancestry – specifically linked to the Knovíz subgroup to have formed between 4 and 3.2 kyr BP, and subsequently expanded across much of Western Europe between 3.2 and 2.8 kyr BP. This ancestry further persisted into the Hallstatt Culture of France, Germany and Austria, impacting Britain by 2.8 kyr BP and Iberia by 2.5 kyr BP.

In other words, this places the putative Proto-Celtic ancestry somewhere in the north-eastern side of the Alps ca. 1300 BC, but not as a local ancestry but rather as one arriving there from the south-east, around northern Serbia and Hungary (which itself had some Anatolian Bronze Age ancestry), which will make further sense when we take a look at the spread of Italic languages.

Italic

A study about the Picenes, from Italy, came out just while I was writing the article mentioned at the beginning of this one, and I mentioned it there saying that there seemed to be no surprise given that the samples looked similar to the other ones we already had from Iron Age Italy (mostly from Etruscans).

Ravasini, F., Kabral, H., Solnik, A. et al. The genomic portrait of the Picene culture provides new insights into the Italic Iron Age and the legacy of the Roman Empire in Central Italy. Genome Biol 25, 292 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-024-03430-4

The study itself states already in the abstract that there are “no major differences between the Picenes and other coeval populations, suggesting a shared genetic history of the Central Italian Iron Age ethnic groups” and just points out that “Nevertheless, a slight genetic differentiation between populations along the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian coasts can be observed, possibly due to different population dynamics in the two sides of Italy and/or genetic contacts across the Adriatic Sea“, while in the main text itself they basically repeat the same basic ideas (emphasis mine, here and thereafter):

Despite cultural differences, the PCA shows that IA populations exhibit relative genetic homogeneity, suggesting a shared genetic origin for these ethnicities in continuity with the former Italian Bronze Age (BA) cultures (Fig. 2A; Additional file 3: Fig. S1)

Again with the further clarification:

Nevertheless, in the context of this genetic homogeneity, we can observe some differences, being the Picenes slightly shifted towards Balkan and Northern European modern populations.

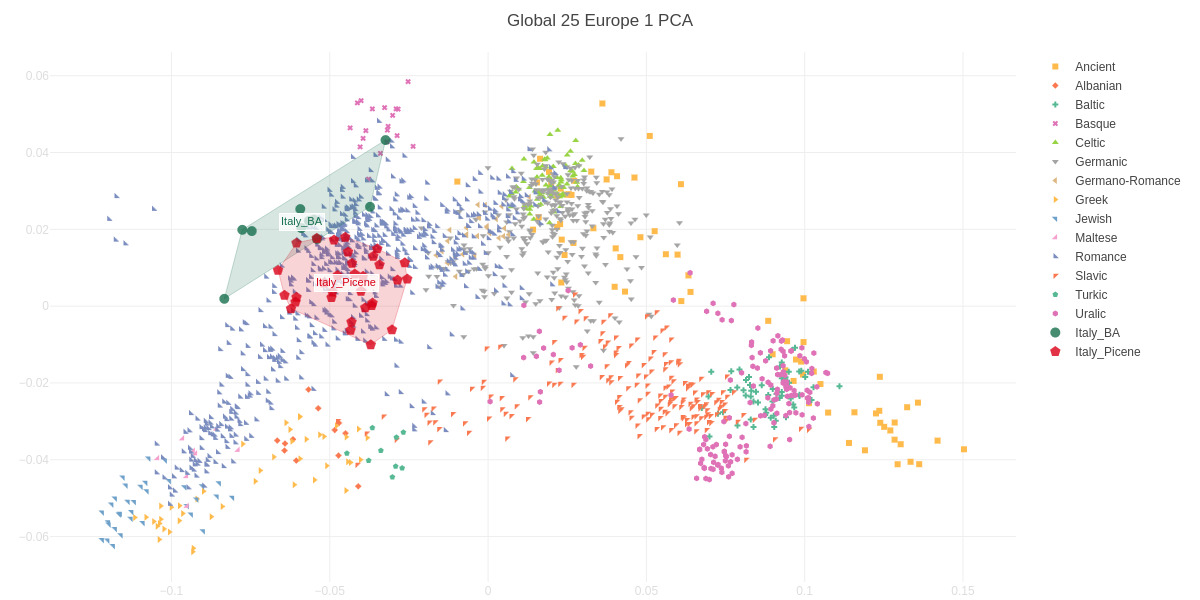

I didn’t have the samples available at the time they published it, but after those samples were included in the Global 25 datasheet (big thanks to Davidski from Eurogenes for keeping updating these datasets) and I could look at them I realised that those were some big understatements. The following PCA with these new Picene samples and the rest of the Italian Bronze Age samples shows already that the former cannot descent directly from the latter (even if it’s true that we lack more BA samples from Italy, but that should not change dramatically what’s already shown here);

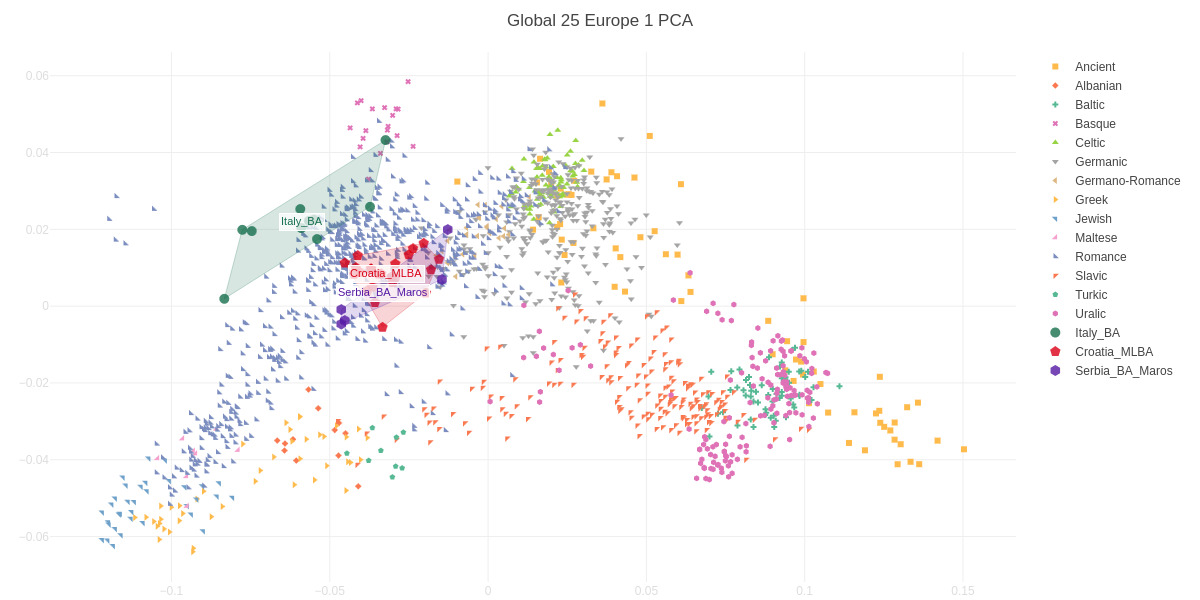

The Picene population falls outside the variation of the previous BA Italian population, with a big shift toward the Balkans (particularly the North-Western part of them):

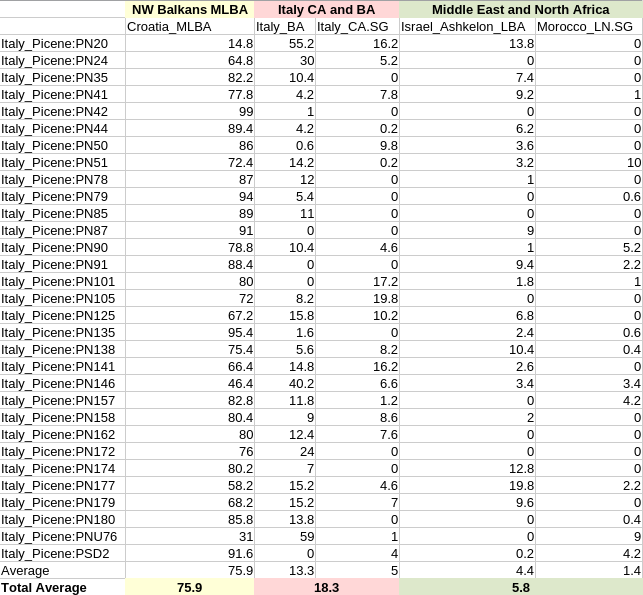

The shift observed there towards the NW Balkans requires not just a small input but quite a massive income of new people. In terms of numbers, here’s a model:

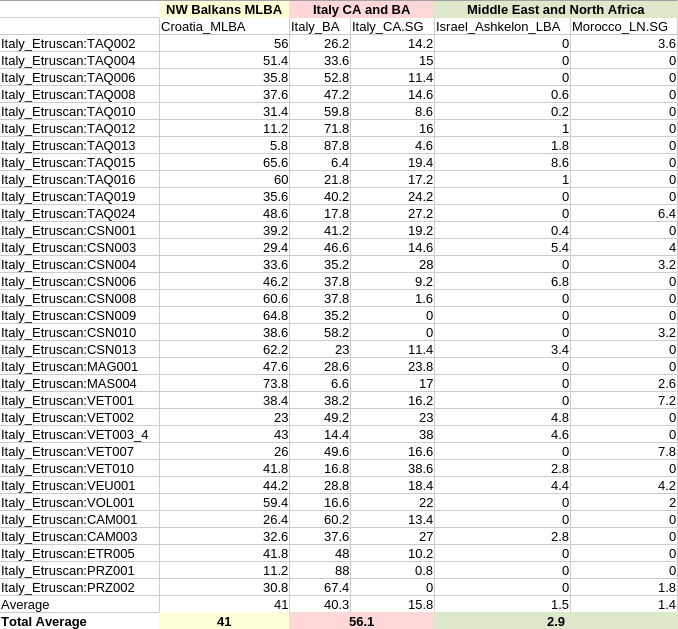

I should stress again that we lack enough samples from Bronze Age Italy, and that with further sampling the number should probably change. But even if that 75.9% NW Balkans (vs. 18.3% local) goes down to 50% or even 40% it’s still a very large genetic impact. In order to get a better perspective, let’s compare now with the Etruscan samples that we have:

While there is also a shift in the Etruscan population towards the Balkans too (probably affected by the same wave from the NW Balkans), they still retain a significant proportion of the previous Bronze Age population. In terms of numbers, using the model as above:

Here too the 41% NW Balkans may be inflated relative to the real one once we have more samples from the BA, but the contrast in both models is very significant and not just a slight difference. In any case, Etruscans were also significantly impacted by those Late Bronze Age (?) migrations from, most likely, the NW Balkans, something almost unavoidable but also consistent with their proposed connection to the Proto-Villanovan > Villanovan culture. It’s just that the impact was significantly lower and for one reason or another it didn’t seem to bring a language shift along with it.

To be fair, the study does provide some further insights into these differences between Picenes and Etruscans, though mostly in the context of Adriatic vs. Tyrrhenian sides of the Italic peninsula:

The putative connection among the Adriatic cultures was further investigated by imputing the genotypes in 815 (new and published) samples and generating a PCA based on the shared identity-by-descent (IBD) fragments between individuals (Additional file 2: Table S10; Additional file 3: Fig. S7A). Notably, we confirmed a significant shift of the Adriatic people toward the Balkan and Central European populations with respect to Etruscans and Italy_IA_Romans (Additional file 3: Fig. S7B).

With respect to the paternal lineages, they also make a similar remark about the trans-Adriatic connection of Picenes:

Similarly, the possible genetic relationship between Northern/Central Europe and the Middle Adriatic region could be supported by the observed material connections between the Hallstatt culture along the Danube River and Northern-Central Italy, already starting from the late BA.

Y chromosome data of the Italic IA groups provide additional evidence to these observations, suggesting that the two scenarios proposed are complementary. Indeed, in the Picenes, two main Y haplogroups are observed, namely R1-M269/L23 (58% of the total) and J2-M172/M12 (25% of the total) (Additional file 1: Table S13), which may be representative of the direct connection to Central Europe and the Balkan peninsula, respectively.

Though the reference to Northern/Central Europe regarding the Y Chromosome R1b-L23 is not very accurate, given that the lineage expanded with the Bell Beaker Culture reaching Italy already in the EBA (ca. 2300 BC). In fact, Etruscans have a higher frequency of that lineage (~75%) while the rest is mostly G2a from the local Neolithic population (see, for example, here), the presence of J2b subclades linked to the Balkans at a frequency of 25% is quite telling (it should be noted too that R1b-L23 also became quite predominant in the NW Balkans during the MLBA).

Lastly, when looking at specific mutations, they also found significant differences related to those that determine the eye and hair pigmentation:

Interestingly, the Picenes (excluding the presumed outliers) have a greater proportion of individuals with blue eyes (26.8%) and blond hair color (22.0%) than other Italic populations. In the Etruscans and Italy_IA_Romans, these lighter phenotypes are much less common (blue eyes: 2.6% in the Etruscans, 10.0% in the Italy_IA_Romans; blonde or dark blond hair: 5.3% in the Etruscans, 10.0% in the Italy_IA_Romans), making these populations more similar to previous individuals from the Italian peninsula.

Ultimately, the study is just a preview of what we’ll probably see once we get many more samples from all the relevant places and periods, but it already points quite clearly to a very significant arrival of new populations to Italy from around 1300-1200 BC (?) that correlate with the putative arrival of Italic languages, and an origin of these in the NW Balkans.

Taken together with what we’ve already seen above about the origins and spread Celtic, it’s becoming increasingly clear that we can safely place Italo-Celtic in the area of Northern Serbia, Hungary and Croatia around 1500 BC, with the split that would give rise to Proto-Celtic happening around that time with a movement up the Danube to the northern part of the eastern Alps, followed by a slightly later movement into the Italic peninsula which would give rise to the Italic languages.

Tocharian

Last year a new papers were published about the Tarim Basin:

Fan Zhang et al. Bronze and Iron Age genomes reveal the integration of diverse ancestries in the Tarim Basin. Current Biology, Volume 35, Issue 15. 2025. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.06.054

Li, H., Wang, B., Yang, X. et al. Ancient genomes shed light on the genetic history of the Iron Age to historical central Xinjiang, northwest China. BMC Biol 23, 93 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-025-02195-x

The first one (brought to my attention by commenter ak2014b, thanks!) is no longer freely available, so I can only comment about it now from memory. It sampled a site at the western edge of the Tarim Basin where it finds the intrusion of an Andronovo related population during the LBA. However, that population disappears and is again replaced by a local one (with high admixture from BMAC), showing that Andronovo tribes didn’t get far into the Tarim Basin and retreated early after. This is unlike the adjacent Tianshan mountains, where the Saka (a group of Scythian tribes) remained throughout the Iron Age as shown in the second paper.

And while writing this, a new one has just been published this year:

Zhao, X., Zhang, D., Sun, B. et al. Tracing bronze to iron age population dynamics in Northwest Xinjiang using ancient time-series genomic data. Genome Biol 27, 33 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-026-03943-0

This last one has samples from a site (Narensu) in the western edge of the Dzungarian basin, with the oldest samples from around 3000 BC representing the IAMC-Afanasievo early contacts that took place in the Altai region just a century or so earlier (and from where the later Chemurchek culture stems from). Probably the most remarkable finding from the study is unrelated to the subject here, but it seems to have the earliest R1b-L51+ sample known to date (a sample labelled NRS_M4_4904BP) dated 3012-2896BC and carrying R1b1a1a1a1a3, a different under the same R1b-L51 marker that characterised the Bell Beaker people.

Anyway, as discussed in the comments of the previous post with ak2014b the most interesting part was to revisit older papers published during the last few years. In particular this one from 2022:

Kumar et al. Bronze and Iron Age population movements underlie Xinjiang population history. Science Vol 376, Issue 6588. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk1534

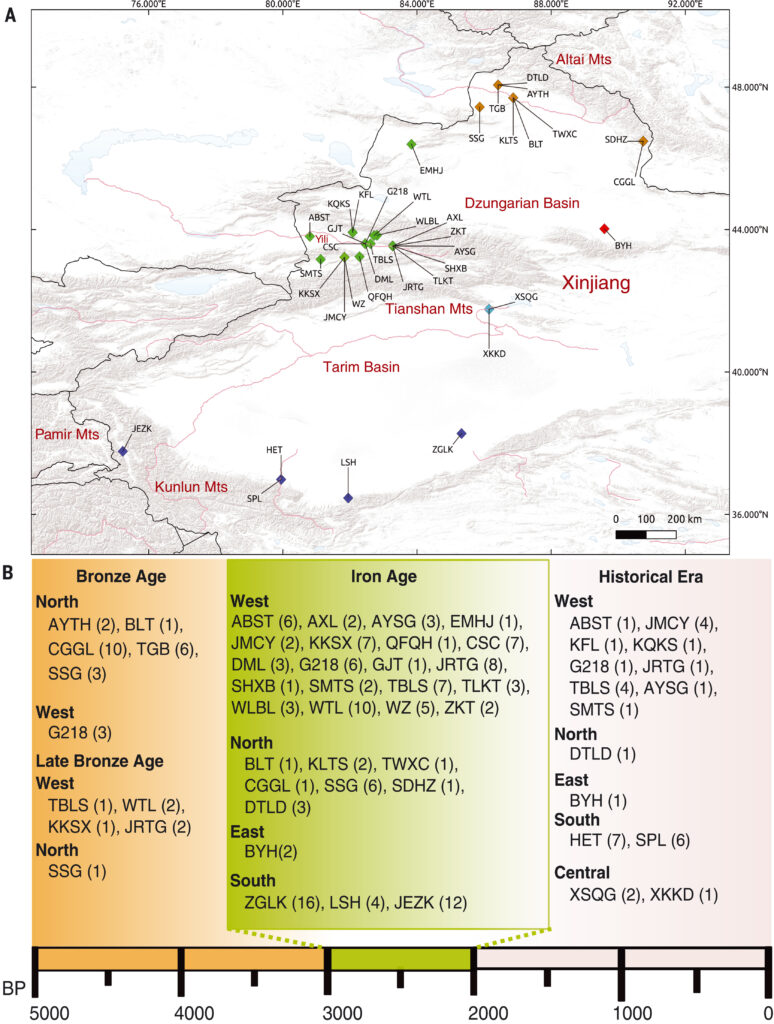

This last paper contains samples from different areas in Xinjiang (Dzungarian Basin, Tianshan Mountains and Tarim Basin) from the Bronze Age, Iron Age and even into the Historical era. The relevant ones when it comes to Tocharian are those in the Tarim Basin that belong to the Iron Age and early Historical era.

To set the scenario that I already talked about in the article mentioned at the top of this post, the earliest evidence of human presence in the region comes from the “Tarim mummies” from the Xiaohe cemetery in the eastern Tarim Basin, dated to the early 2nd mill. (ca. 2000-1800 BC). We already got DNA from those specimens and they turned out to belong to the population that was also present along the Inner Asia Mountain Corridor (IAMC) that runs from the eastern part of the BMAC to the Altai Mountains. That population was an early pastoralist one that was unknown until quite recently when Michael Frachetti and others started to find sites like Tasbas or Begash along the IAMC dating to the EBA. In these sites, seeds from barley (acquired from the BMAC) and millet (brought from China) have been found, showing how this mobile pastoralists played a significant role in the transfer of goods between East and West Eurasia. A sample from this population dating to ca. 2700 BC has been DNA sequenced and by that time it already shows some admixture from both BMAC and Afanasievo, the populations that were at the south and north edges respectively of their IAMC range. However, and quite remarkably, the samples mentioned above from the Xiaohe cemetery that date to some 900 years later didn’t show any of this admixture, hinting at an isolation since at least around 3000 BC from the main group that moved through the IAMC. Another find from these last samples was that they belonged to a very rare paternal lineage (R1b2-PH155) that is specific to that region of southern Central Asia and had only been found on another sample from Dzharkutan (late BMAC period).

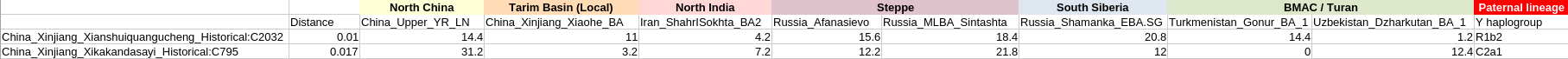

Back to the samples from the Kumar et al. 2022 paper, there are two sites that are pretty much in the Tocharian speaking area and from where they obtained 3 samples from around 200-450 CE. The sites in question are Xianshuiquangucheng (XSQG) and Xikakandasayi (XKKD) in the north eastern Tarim Basin (see map below from the paper itself), very close to the ancient city of Agni (towards Korla in this map), around the border between the areas marked as Tocharian A and Tocharian B speaking ones.

The two individuals from the first of those sites (XSQG) are males, and both belong to Y haplogroup R1b2 (R1b2 and R1b2b2 respectively), the same lineage found in the Tarim mummies from Xiaohe, while the other individual from the second site is a male too, but his Y chromosome is under C2a1, probably of South Siberian origin. The persistence of the R1b2 lineage from the Bronze Age to the Historical period is an incredibly remarkable finding, and it’s only the lack of information from those two sites where the latter samples come from that prevents us from saying with certainty if they may have been speakers of the Tocharian language or not (though it does look quite possible). It’s a shame that the authors of the study mixed up that lineage with R1b1, which is the typical from EBA steppe populations like Yamnaya or Afanasievo. Both lineages are unrelated (separated some 20,000 years ago), yet the study says this about it in the supplementary text:

“Fig. S26. Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal haplogroups of ancient Xinjiang individuals.

Xinjiang individuals are divided into groups of Bronze Age (BA), Historical Era (HE), and Iron Age North (IA). Geographical orientation is depicted as North (_N), South (_S), West (_W), East (_E), and Central (_C). For the BA individuals, we observe more of the R1b1/R1b2 Y-haplogroup typical of Steppe EMBA populations, whereas the IA more typically have the R1a1 Y-haplogroup associated with Steppe_MLBA populations.”

Should the authors had known that R1b1 and R1b2 are absolutely not the same thing, both with different distribution and representing different populations, the study would have made a much bigger impact. Nevertheless, the data is there which is what really matters.

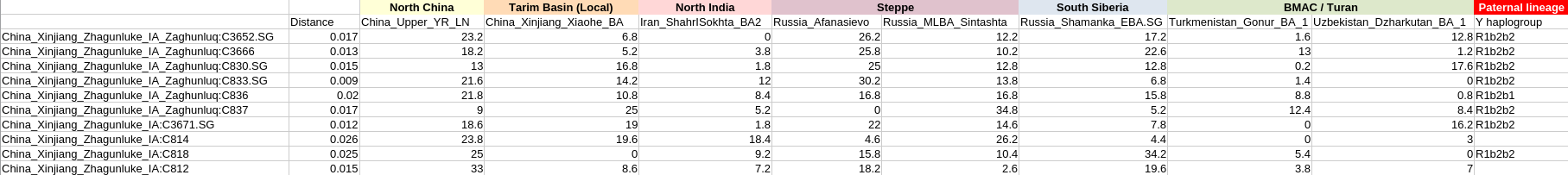

This R1b2 haplogroup is also found in most of the individuals (Iron Age) from the site of Zhagunluke (ZGLK), in the southern Tarim Basin, in the area of putative (and dubious) Tocharian C speaking people.

When it comes to the genome wide genetics from those 3 putative Tocharian (A and/or B) speaking samples, they are very admixed, as expected, with little left of their original “Xiaohe” substrate and much from North China (Upper Yellow River is a good match from available sources), Steppe (both Sintashta and Afanasievo), North East Asian/South Siberian (Shamanka_EBA like) some BMAC and less from North India. A typical pattern of a small population on a trade route, where inter-marriages were usually the best form of alliance for all parties involved (usually female mediated, more rarely by marrying a male son into the other community).

Below are the IA sample from the Zhagunluke site in the southern Tarim Basin:

We’ll have to wait for more samples of reliable Tocharian speakers (and in general more from the northern part of the Tarim Basin, throughout the IA), but as usual we shouldn’t expect them to be any different from those few putative ones.

When it comes to Tocharian, options were always very limited. On one side, we had the steppe option through the Afanasievo culture. It had significant linguistic and archaeological problems, but now we also know that there’s no genetic evidence that they ever settled in the Tarim Basin.

Fortunately, archaeology came up with another option that made much more sense when they found this pastoralist population from the IAMC that was involved in trade between the BMAC and China (by the way, as mentioned in the comments that led writing this, Tocharian has loanwords from Old Chinese – check in this video, for example). With this population having millet from China, and early West Asian domestic sheep being found in China, archaeology aligned well with linguistics. Then genetic evidence came to confirm that it was this population the one that first settled in the Tarim Basin in the BA, and later we’ve found out that there seems to be continuity from this population even into the Historical Era where and when Tocharian was spoken.