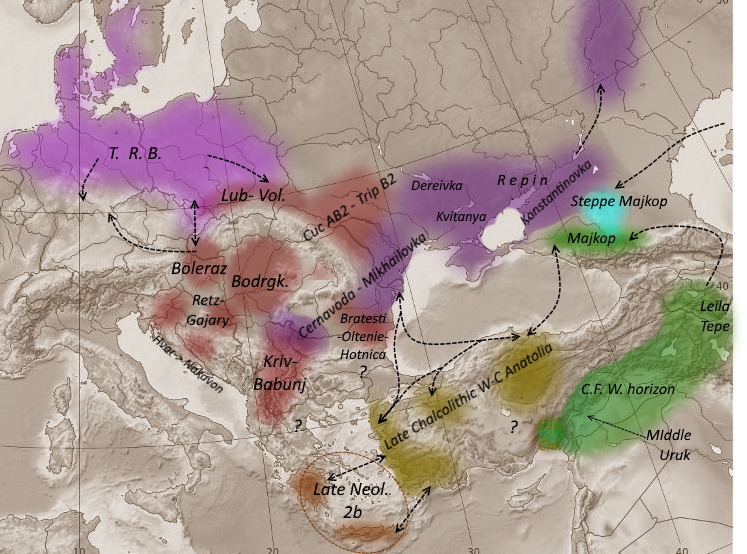

As a brief fill-in, I will look at what the recent data adds to our understanding of the 4000 – 3000 BC period in northwestern Eurasia, which corresponds to the critical ‘’transition’’ period between the collapse of ‘’Old Europe’’ and arrival of steppe migrants. In reality, events are of course more complex, if one understands the totality of the data, and what is even more exciting is understanding how events in northwestern Asia tie in with those in Europe. In place of a long didactic post, I will address some key questions:

1) Are Uruk colonists behind the Majkop phenomenon?

This is a negative, even by chronological criteria alone. The push by Uruk colonists from south Mesopotamia toward its northern frontier occurred during the middle Uruk phase, c. 3700 BC. By this time, Majkop already existed, some 1000 km to the north.

Rather, the origin of the Majkop phenomenon probably emerges from the Late Chalcolithic koine in East Anatolia & southern Caucasus – the ‘’Chaff-Face Ware horizon’’, which would also subsume regional variants and special cases, such as the Leila Tepe culture in Azerbaijan (which also featured kurgans). The lack of Levant-type admixture is further evidence against an Uruk origin for Majkop.

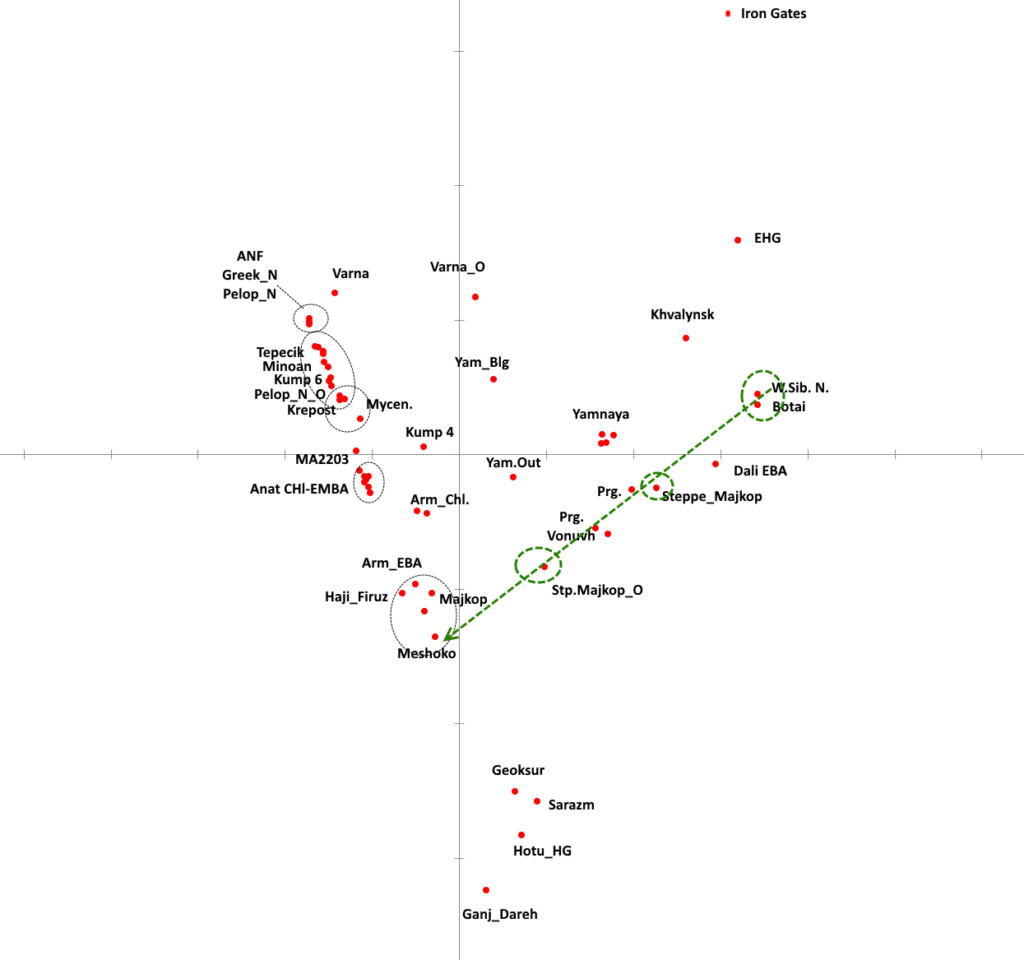

Whilst Wang et al. bundle Meshoko with Majkop, they are actually rather distinctive (the former feature austere funerary gifts, and are associated with fortified settlements; whilst they were disused during Majkop period, and funerary wealth reached a peak). As per Trifinov, the appearance of Meshoko group seem to me as rustic mountain farmers from Darkveti culture moving north over the mountains; and therefore Majkop might represent a second, later movement (although the genetic data can also be explained by a constant trickling of people, instead of clearly defined migration horizon).

Darkveti-Meshoko:I2056

CHG 58.9%

Tepecik_Ciftlik_N 21.2%

Hajji_Firuz_ChL 19.3%

EHG 0.6%

Levant_N 0%

d: 2.7%

Maykop_Novosvobodnaya

CHG 40.7%

Hajji_Firuz_ChL 39.2%

Tepecik_Ciftlik_N 17.3%

EHG 2.3%

D: 2.26%

2) The mysterious ”Steppe Majkop”.

This archaeological unit is characterised by tumuli burials, a pastoralist economy and presence of Majkop-styled ceramics as burial gifts. This group spread out along the Piedmont steppe, apparently displacing (& absorbing some of) the preceding ‘’Eneolithic Steppe’’ populace.

I would hypothesize that these are new migrants to the Fore-Caucasus, being part of an intricate network of exchange ushered in by the appearance of Majkop- a ‘’pull effect’’. The exotica of Central Asian origins (e.g. lapis lazuli) might have been brought by these groups, and they might also have introduced certain forms of pastoralism into the western steppe.

Steppe_Maykop:

West_Siberia_N 41.1%

Progress 37.7%

Sarazm_Eneolithic 17%

Darkveti-Meshoko:I2056 4.2%

d:1.74%

As can be visualized, Steppe Majkop lie on a cline between so-called ‘West Siberian Neolithic” & Majkop-proper.

3) The ”Neolithic Cline”

This is a huge topic in itself, so these are some brief comments. We observe the close relationship between West Anatolian, Greek and early European farmers. However, these must represent a local subset/ founder effect, because we know that even within Anatolia there are individuals which lie somewhat further toward the Iran/CHG pole (Tepecik, from central Anatolia, Krepost- Neolithic Bulgaria; and according to some friendly ‘word -of -mouth’, Early Italian Farmers).

As the Neolithic progressed, individuals from Greece and Western Anatolia shift somewhat eastward, perhaps as part of ongoing admixture & contacts across an north Mediterranean Neolithic koine.

More striking, however, are the series of population shifts within Anatolia between 5000 and 3000 BC. As we know, the south central Anatolian plain (Cappadocia, etc) served as a vital demographic & cultural hub for the Neolithic progression further west (even if pockets of pre-Neolithic communities in west Anatolia were genetically similar). It is therefore quite remarkable that this regions sinks into obscurity after 5000 BC. Although some of this is research related, there must be other reasons, such as land and population exhaustion. Indeed, it is perhaps no coincidence that from c. 5000 BC, north central Anatolia and the Sinope peninsula now become dotted with settlements, having been something of a terra incognita during the Neolithic. It therefore seems that the link between the East and the West Pontic region ran predominantly via northern Anatolia, perhaps via a interconnecting web of seaborne contacts. As noted previously, the sample ‘’Anatolia Chalcolithic’’ (Barcin Hoyuk, c. 3800 cal BC) represents a significant shift compared to pre-4000 West Anatolian Neolithics.

Anatolia_ChL

Barcin_N 41.2%

Maykop_Novosvobodnaya 36.9%

Hajji_Firuz_ChL 18.2%

West_Siberia_N 2.3%

That it can be modelled as descending from, or sharing ancestry with the Majkop phenomenon dovetails with the appearance of novel cultural groups in western Anatolia (still to be fully understood), bringing with them new technologies, e.g. arseniccal bronzes. At the same time, ideas and individuals might also moved from Europe back to Anatolia, since at least 4500 BC, during the Varna-Karanovo VI period, and this continued as late as 3300 BC (Cernavoda, Usatavo). Naturally, this paragraph does not do justice to such a topic, and indeed much more genetic data and clarification of some lingering chronological issues are needed to fully tackle this issue.

4) The genesis of the Kurgan phenomenon

Marija Gimbutas had astutely observed a series of phenomena manifesting as ‘’waves’’ through Europe, and the ”general gist” of her views have held up. However, we can now refine these with our more developed theoretical backgrounds, a clearer understanding of chronology, new finds, and of course, aDNA. We now understand that various ‘’Kurganized’’ groups like Majkop, Remedello, Baden-Boleraz and GAC do not show any steppe ancestry. Even in the heart of the Hungarian steppe, we see Late Chalcolithic, in-kurganed individuals without steppe ancestry, belonging to Y-hg G2a. These phenomena therefore represent a series of societal changes which occurred as part of an interaction and competition between disparate but inter-connected post-Neolithic groups spanning from central Europe to central Asia; associated with the Secondary Products evolution, wheel-traction complex, metallurgy, etc.

Globular_Amphora

Tiszapolgar_ECA 80.4%

Baltic_HG:Spiginas4 17.5%

Trypillia 2.1%

Ukraine_N 0%

Maykop_Novosvobodnaya 0%

Khvalynsk_Eneolithic 0%

Progress_Eneolithic:PG2004 0%

Distance 2.7302%

Protoboleraz_LCA

Tiszapolgar_ECA 93.5%

Maykop_Novosvobodnaya 3%

Baltic_HG:Spiginas4 2.2%

Trypillia 0.9%

Ukraine_N 0.4%

Khvalynsk_Eneolithic 0%

Progress_Eneolithic:PG2004 0%

Distance 2.1265%

Whilst we lack Cernavoda & Usatavo samples, we do have some Early Bronze Age samples from Bulgaria – c. 3200-2500 BC, which date to after the collapse.

Of course, later in the MLBA, steppe ancestry rises significantly in the northern Balkans (e.g. the Croatian MLBA sample set), but that is for a future analysis.

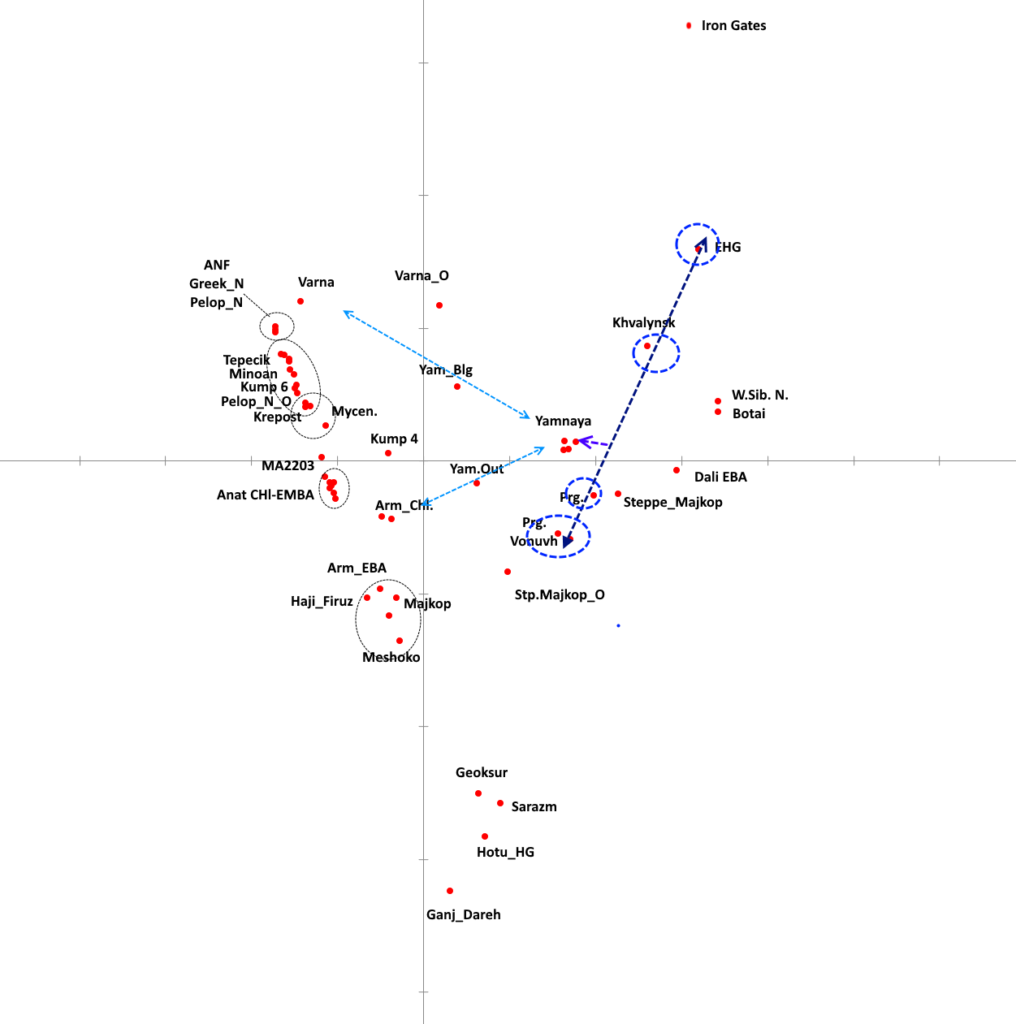

4a) The Formation of Yamnaya.

Leaving aside the still debated question about the ultimate source of the ”CHG” admixture in Eneolithic Steppe, an expansion from the Don-Kuban steppe seems to have been the main driver, rather than Khvalynsk. Whatver the case, we can see that Yamnaya is a more ”farmer shifted” fusion of Progress & Khvalynsk (crudely speaking); and the source of the ANF shift must be, both, Majkop and Cucuteni groups.

It is curious that ”outlier” individuals can be found both north and south of the Black Sea, suggesting bilateral admixture & mobility.

Rob,

great post! Thx for helping me out, and I also appreciate that you have taken over some of the issues I had on my “to write list”, especially as concerns Meshoko and Yamnaya, which will allow me to shorten upcoming posts.

Some comments:

A. Meshoko:

The G25 simulations suggest to me that the Meshoko genesis is more complicated than a simple “move across the mountains” from Colchis (and the “Meshoko-Darkveti” labelling is also somewhat misleading):

1. The “Darkveti” concept itself is ill-defined. Technically, “Darkveti” also covers the late Mesolithic, including Kotias just a few km across the river from the Darkveti site. The overall neolithisation process of Colchis is so far poorly understood, both as concerns pottery, as farming. What emerges, however, is that Colchis wasn’t culturally homogenous during the 5th/6th mBC. A cave-based, probably still aceramic and for a long time hunting-gathering culture in the Imeretian mountains contrasts with light wattle-and-daub housing in the plain, and stable settlements with comparatively early use of pottery and aquisition of obsidian from ca. 300 km further East on the SW coast (Kobuleti, Anaseuli I etc.).

http://iae.am/sites/default/files/database/Badalyan%20Obsidian%202010.pdf

To me, it appears that this latter, coastal group, which seems to first have expanded north along the coast before crossing the mountains into Adygea, is a main source of Meshoko. Features like Meshoko’s wattle-and-daub architecture, and the pre-dominance of pigs in both Colchian and Meshoko archeofaunal remains certainly speak for a strong relation.

[Intriguingly, the toponym “Meshoko” recalls the ancient Moschoi, whom Herodotus located in SW Georgia on the Black Sea coast and across the Meskheti range into Meskheti (Samtskhe) on the Upper Kura – however, that toponym should rather go back to a Kartvelian expansion during the LBA/ early IA than signal eneolithic continuity]

2. Meshoko had a well-developed copper metalurgy that has traditionally been linked to Balkan (Varna) influence. However, G25 modelling refutes such connection, Meshoko prefers W. Asian Neolithic sources instead, which substantiates Courcier’s claim for a local, i.e. Caucasian root.

http://www.academia.edu/5789550/2014_-_Ancient_Metallurgy_in_the_Caucasus_From_the_Sixth_to_the_Third_Millennium_BCE

Courcier lists a number of metal finds from Colchis. However, the “Darkveti” repertoire differs from Meshoko. Moreover, Kushnareva 1997 assigns the sites in question to the Eneolithic that according to her in Colchis did only commence by the early 4th mBC. This puts the focus on the Sioni Culture that especially at Mentesh Tepe presented a full-fledged operational chain with a repertoire similar to Meshoko.

Another Sioni link stems from Obsidian – Meshoko used obsidian from Mt. Chikiani (Paravani Lake) in the S. Georgian uplands. While the manifold archeological monuments (mines, Kurgans, Menhirs etc.) around the Paravani lake most likely “only” date to Kura-Araxes and later periods, the nearby Bavra Ablari rockshelter has provided a comprehensive set of Sioni artefacts, including evidence of domesticated cattle, and Einkorn and wheat agriculture, AMS dated to 4,700-4,000 BC.

http://www.academia.edu/31205652/From_the_Mesolithic_to_the_Chalcolithic_in_the_South_Caucasus_New_data_from_the_Bavra_Ablari_rock_shelter

3. I find it intriguing, but also puzzling, that Tepecik-Ciftlik is the preferred ANF choice – it is far too Western for my taste. One might of course speculate about a northward expansion out of Cappadocia towards the coast near Sinope, which is what you seem to hint at. However, the coastal mountains are quite high and difficult to pass. Moreover, since Tepecik-Ciftlik incorporates a substantial Natufian component (around 20%, IIRC), shouldn’t we then find this component later on also in Anatolia_CHL?

Alternatively, we may assume that Cayönü had a similar Natufian component as Tepecik-Ciftlik, because both sites were involved in Obsidian trade to Jericho since the PPN (Cappadocian Obsidian in the case of Tepecik Ciftlik, Bingöl Obsidian from Cayönü). Cayönü has in many ways been linked to Caucasia. E.g., Mesolithic Armenian Kmlo tools have often been related to Cayönü tools. Moreover, Cayönü, which in addition to the Levante also supplied the Western Zagros flanks (Jarmo etc.) looks like the logical hub for disseminating PPN innovations like polished axes, straight shafteners etc. from and to the Levante and the Zagros, but also (via Upper Euphrates and Araxes) to the Caucasus and beyond. As such, it is IMO also the most likely candidate to have stimulated the emergence of Shulaveri-Shomu, especially when considering features like irrigation agriculture on alluvial floodplains that ShuSho shares with Jarmo and the Jordan valley, but that seem to be less common in the Zagros.

In short, Tepecik-Ciflik may represent the best available proxy for the Neolithic adstrate in ShuSho – maybe not in ShuSho as a whole, rather in the Armenian sites that are connected, yet somewhat different from it.

4. This takes me to Armenia_CA. The Areni Cave, from which the samples have been taken, has provided a diverse pottery spectrum that a/o included some 10% of Meshoko “Pearl-ornamented” pottery. So, an Armenian connection certainly exists. Whether Arm_CA is the adequate source to capture that connection is another question – it has remained unclear to me which of the apparently several cultures present at that site it actually represents.

5. Finally, there is the Haji Firuz element. chronologically somewhat early, but from the Urmia Lake area that has supplied various cultural influences into Caucasia, be it the 6th mBC Mil Steppe Neolithic in Lower Karabakh, possible influence on Neolithic Chokh in Dagestan, or participation in the Chaff Faced Ware horizon that is not only represented by Leyla Tepe, but also among the various ceramic styles encountered in Areni 1. Makes sense…

In summary, With its fortified (or better: enclosed?) settlements, fully developed agriculture, own metalurgy including evidence of smelting local ores, Meshoko clearly doesn’t look like “rustic mountain farmers trickling in over the mountains”. Instead, it appears to be a quite complex assemblage of different influences from Colchis, the Georgian upland (Sioni), Armenia, Urmia Lake and possibly even Dagestan (Neolithic Chokh seems to disappear at about the same time as Meshoko appears). I just wonder where that “assemblage” took place…

Hi Frank. Thanks for your points, which I will reply in turn.

”The “Darkveti” concept itself is ill-defined. Technically, “Darkveti” also covers the late Mesolithic, including Kotias just a few km across the river from the Darkveti site. The overall neolithisation process of Colchis is so far poorly understood, both as concerns pottery, as farming. What emerges, however, is that Colchis wasn’t culturally homogenous during the 5th/6th mBC. A cave-based, probably still aceramic and for a long time hunting-gathering culture in the Imeretian mountains contrasts with light wattle-and-daub housing in the plain, and stable settlements with comparatively early use of pottery and aquisition of obsidian from ca. 300 km further East on the SW coast (Kobuleti, Anaseuli I etc.).”

That’s interesting. So a coastal expansion in western Georgia ?

” Meshoko had a well-developed copper metalurgy that has traditionally been linked to Balkan (Varna) influence. However, G25 modelling refutes such connection, Meshoko prefers W. Asian Neolithic sources instead, which substantiates Courcier’s claim for a local, i.e. Caucasian root.”

I agree that it was largely of local origin, however I don’t think that the lack of EEF in Meshoko negates contact with Balkan copper traditions, as it does in Khvalynsk, which lacks much if any EEF yet had obvious contact with the Varna, C-T, etc.

Meshoko was the final link in the Sredni Stog network, and its appearance north c. 47/ 4500 BC synchronises with it.

”I find it intriguing, but also puzzling, that Tepecik-Ciftlik is the preferred ANF choice – it is far too Western for my taste. One might of course speculate about a northward expansion out of Cappadocia towards the coast near Sinope, which is what you seem to hint at. However, the coastal mountains are quite high and difficult to pass. Moreover, since Tepecik-Ciftlik incorporates a substantial Natufian component (around 20%, IIRC), shouldn’t we then find this component later on also in Anatolia_CHL?”

I don’t think we should take results literally. With 20% Tepecik, 20% Haji FIruz, it’s just approximating a population which existed south of the Caucasus, or NE Anatolia, which makes sense if it expanded along the west coast ?

”Meshoko clearly doesn’t look like “rustic mountain farmers trickling in over the mountains”. Instead, it appears to be a quite complex assemblage of different influences from Colchis, the Georgian upland (Sioni), Armenia, Urmia Lake and possibly even Dagestan ”

I certainly agree that Meshoko feature a multifaceted cultural package. However, it wasn’t Majkop or Varna. People were buried with animal tooth pendants. It definitely has a ‘rustic’ feel to it, and had a large local Mesolithic origin.

Rob:

1. “A coastal Expansion in Western Georgia?”

Well, that’s at least the model brought forward by Trifonov 2015. He explains Meshoko’s pig-breeding economy from a spread of forest-based pigholding along the Black Sea shores, first to Abkhazia, than to the Sochi area and the Kuban, finally across the mountains, which took avantage of the expansion of oak and chestnut forests permitted by gradually increasing rainfall during the 6th/ early 5th mBC.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282818823_Viktor_Trifonov_2015_Berge_und_die_Ebenen_ein_Modell_der_kulturellen_Entwicklung_im_Wesrlichen_Kaukasus_im_5_und_3_Jt_vChr_Der_Kaukasus_im_Spannungsfeld_zwischen_Osteuropa_und_Vorderem_Orient_Dialog_d

My impression is that there is especially good correlation between Meshoko Cave (alternatively labelled Kamennomost Cave) and eneolithic cave sites around Adler and Sochi. However, as I have said, this probably only covers part of the Meshoko genesis. The Meshoko settlement near the cave seems to already display quite different features.

2. ” had a large local Mesolithic origin.”

Depends what you mean by “local”. There wasn’t any Neolithic in Adygea – the Gubs Gorge caves and otherUP/ Mesolithic sites all show a hiatus between the Mesolithic and the Eneolithic/ Chalcolithic. As for the Sochi-Adler area caves, I am unaware about their stratigraphy – maybe there was some kind of Meso-Neo-Eneolithic continuity, maybe not. Available reports almost exclusively deal with the Neandertal finds there, at best straddling the Upper Paleolithic, everything else is under “further ran”….

3. “I don’t think that the lack of EEF in Meshoko negates contact with Balkan copper traditions, as it does in Khvalynsk, which lacks much if any EEF yet had obvious contact with the Varna, C-T, etc.

a.) The theory of Khvalynsk contact to Varna, C-T etc. is strongly based on the old assumption that “pure copper” (i.e. w/o traces of arsenic) artefacts must originate from the Balkans. As Courcier (see link in my first comment) points out, such “pure copper” artefacts, and corresponding ores, have in the meantime also been found along the Middle Kura, e.g. Mentesh Tepe (Sioni Culture). Since Khvalynsk shows substantial connections to the Caucasus (greenstone necklaces, steatite beads, c.f. Anthony 2007), much of their copper may have been of Caucasian rather than Balkan origin. Additional archeometalurgical study of the Khvalynsk copper is required.

b. Otherwise, I aggree. Russian researchers, in their classical “lumping approach”, tended to construct a Cis-Caucasian eneolithic cultural entity, alternatively labelled a/o as “Trans-Kuban” (Zakubansky), Meshoko-Darkveti,

Svobodnoe-Meshoko-Zamok, or Pearl Pottery Culture. Western research (Kohl, Lyonnet etc.) remained more sceptical in this respect and preferred to treat each unit separately . Rightly so – aDNA now shows that Meshoko differed fundamentally from the eastern Elbrus foothills eneolithic (Zamok, Vonyushka, Progress, Nalchik, in NW >SE order like pearls on a string along the Rostov/Don-Vladikavkaz [->Tbilissi/Baku] road).

Against this background, one may question the so-far assumed identity between Meshoko and the Svobodnoe cluster of settlements along the Kuban a good 100 km north of Meshoko. Anthony 2007 (p. 407ff) already points at significant differences in terms of pottery and subsistence (pig & cattle breeding at Meshoko, wool sheep plus hunting/ fishing at Svobodnoe, albeit both have provided evidence of wheat and barley farming). The Svobodnoe settlement layout – a 1 ha large enclosure with 30-40 wattle & daub houses along the inner wall around a large, empty central area possibly used for cattle herding – has no Caucasian parallels that I am aware of but is instead reminiscent of Trypolye “megacities”.

On the Staronizhesteblievskaya site on the Lower Kuban, acc. to https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Культура_накольчатой_жемчужной_керамики a Pearl Pottery culture site, the excavators state: ” The burial rite has parallels among cemeteries of the Novodanilovka type whereas the grave inventory finds parallels in the sites of the Mariupol type“.

https://www.e-anthropology.com/English/Catalog/Archaeology/STM_DWL_xeDH_Undx94bAsrwA.aspx

Frank,

”Depends what you mean by “local”. There wasn’t any Neolithic in Adygea – the Gubs Gorge caves and otherUP/ Mesolithic sites all show a hiatus between the Mesolithic and the Eneolithic/ Chalcolithic. ”

Yes we’re talking about the Darkveti predecessor being largely local, south of the Caucasus. Obviously Meshoko (north of the Caucasus) only appears c. 4500 BC

”Additional archeometalurgical study of the Khvalynsk copper is required.”

Yep quite true

Just finished reading Kosintzew 2017: “A Generalized Assessment of Cultural Changes at Stratified Sites: The Case of Chalcolithic Fortresses in Northwestern Caucasus”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315970096

He decribes: “Interaction of two cultures differing in origin. The earlier culture, associated with the constructors of the Meshoko fortress, shows no local roots, and was evidently introduced from Transcaucasia. The one that replaced it was significantly more archaic (a few copper tools notwithstanding), and reveals local Neolithic roots. It alone can be termed the culture of ceramics with interior punched node decoration [read: Pearl Pottery]. The ceramics of Yasenova Polyana, too, indicate cultural heterogeneity and two occupation

stages; but cultural changes are more complicated there, probably because the site existed longer, and more than two cultural components were involved.”

With the second, more archaic culture with “local roots” he means Svobodnoe on the Lower Kuban. “Local roots” is somewhat misleading in this respect, because the Svobodnoe sites also seem to only date to the mid 5th cBC. Except for a handful of sites (mostly fireplaces) along the Kuma-Manych depression, no “Neolithic” (6th mBC) finds are known south of the Sea of Azov/ Lower Don (see Gorelik e.a. 2014, Abb. 1; http://www.academia.edu/35247733/A._Gorelik_A._Cybrij_and_V._Cybrij._Zu_kaukasischen_und_vorderasiatischen_Einflüßen_bei_der_Neolithisierung_im_unteren_Donbecken._Eurasia_Antiqua_20-2014_143-170 ).

Kosintzew describes the “archaic pottery” as shell-tempered, typical of Rakushechny Yar and later Dniepr-Donets, and synchronises it with Skelya/ Novodanilovka, and Cucuteni C. If he is correct, the presence of Pearl Pottery in Areni 1 would mean some migration from the Azov area into Armenia, which could explain the EHG in Arm_CA.

In general, the Ciscaucasian Eneolithic seems to have been far more complex than assumed so far. Hardly populated during the Neolithic, a more humid 5th mBC climate seems to have attracted immigrants from all directions to the region: Don-Azov, probably also the Lower Volga, Colchis, East Transcaucasia, maybe even arrival from across the Caspian Sea by boat and along the Kuma and Terek. The Wang e.a. paper may just be the starting point in grasping that complexity – more samples, e.g. Svobodnoe, upper Meshoko levels, also sites from the Manych basin would help better understanding. E.g., w/o the latter, it is IMO impossible to decide whether “Steppe Maykop” represents a recent (mid 4th mBC) arrival from Central Asia, or such populations were aready present there earlier.

What I find intriguing in this context is how similar Maykop aDNA seems to be to Meshoko, even though the original Meshoko settlers apparently were replaced by Svobodnoe populations. Could someone model Maykop with Meshoko as source, to better grasp the role of the latter in the Maykop genesis?

Hi FrankN ,

See slide 4600BC in “https://shulaverianhypothesis.blogs.sapo.pt/”

There is a box there that says:

“MESHOKO, the fortified place is being attacked from the south. It’s the formation of what is clearly the first of two completely differentiated cultures in Meshoko. All it will remain later is the copper awls”

OM:

There are a lot of good ideas within your ShuSho hypothesis, but sometimes you have it pretty wrong. Unfortunately, this is one of such cases:

1. There is hardly anything suggesting a ShuSho element in lower level Meshoko. Instead, we are dealing with strong Colchian roots, plus most likely Sioni influence, maybe already some Proto-Leyla Tepe/ CFW/ Urmia lake (the fortification component, possibly introduced from/via Chokh/ Dagestan).

2. Lower Level Meshoko wasn’t overrun from the South, but from the North (Svobodnoe, connected to the Dniepr-Don Neolithic). Intriguingly, Meshoko-like ancestry reappears again with the next “southern” incursion, namely Maykop. And while the Elbrus piedmont Eneolithic (Vonyushka, Progress) still requires interpretation, which I intend to deliver elsewhere, it is pretty obvious that it didn’t survive the Maykop expansion – two of the four Maykop-Novosvobodnaya samples stem from sites very close to Progress, and have very little to do aDNA-wise with the Elbrus piedmont Eneolithic.

3. If one wants to look for an early ShuSho expansion across the Caucasus, the eye shouldn’t go to Meshoko, but instead to the Sursk culture around the Dniepr Rapids, and/or early Azov-Dniepr (Mariopol) – a possibility long envisaged by some E. European archeologists, and recently also taken up by Gronenborn (Cologne University). In fact, that would rather have been ShuSho’s Armenian sibling, Arashten. We have a credible archeological path (Chokh/ Dagestan, plus the Neolithic finds along the Kuma-Manych Depression), evidence of Armenian Obsidian in Surksk/Azov Dniepr, and a clear, albeit modest, CHG signal showing up on the Dniepr Rapids during the second half of the 6th mBC (compare my CHG-Steppe Part II). I intend to explore this issue further in my upcoming Part III – stay tuned.

Steppe Maykop is a recent arrival. Got a post coming. Early Maykop is about 80% Armenia ChL-like, and the rest like Meshoko. I’ll get to that soon .

Thx for the info, Chad.

Btw – I wanted to comment on your blog, but it doesn’t accept login with Google. Any possibility to change that?

I’ll see what I can do about it

Rob – let me add on the Kurgan point:

Rassamakin 2012 distinguishes two phases:

1. An initial phase of “small natural hills as a burial marker; simple, small, stone or earthen constructions; burials in pits, catacombs or stone cists in pits” starting ca. 4750 BC,

2. “First ritual monumental architecture: ditches, cromlechs, stone circles, round and long barrows of black earthen and yellow clay, stone cairns; burials in pits, stone and wooden cists,“, the earliest example of which given by him (Vynogradne, Azov area) dates to ca. 3,750 BC.

http://www.persee.fr/doc/mom_2259-4884_2012_act_58_1_3470

The initial phase is relevant from a regional point of view, but nothing special in the West Eurasian context. Stone-covered burials, partly marked by large tombstones are, e.g. known from PPNB and early PN in the Levante.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_2015_num_41_2_5679

The Mesolithic cemetery of Groß Fredewalde near the Lower Oder (late 8th to early 6th mBC) had pit burials in a natural hill, and a more in-depth research will probably uncover many more Mesolithic/ Neolithic examples that confirm to the criteria set. In fact, it is often theoreticised that the idea of burial mounds sprang from shell midden burials, of which is no lack in Mesolithic Iberia, Scandinavia and elsewhere.

When turning to the first “real monumental” Kurgans, one should note that the Vynogradne example post-dates the Leyla Tepe Kurgan of Soyuq Bulag, the main burial of which has been AMS-dated to 3951-3759 BC (btw with the so far earliest finds of Lapis Lazuli in Caucasia and as such providing a terminus ante quem for trade relations with Central Asia). The excavators see architectural parallels to the Sé Girdan Kurgans in the Urmia basin, and compare the grave goods repertoire to Sarazm.

http://www.academia.edu/4647028/2008-_Late_Chalcolithic_Kurgans_in_Transcaucasia._The_cemetery_of_Soyuq_Bulaq_Azerbaijan_

The Vynogradne Kurgans furthermore somewhat post-date the emergence of Maykop, albeit exact dates of the Maykop kurgans are yet lacking. The same applies to Cernavoda I, which has equally delivered various Kurgans.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/mom_2259-4884_2012_act_58_1_3471

Rassamakin describes finds of CT pottery in post-Stog and Lower Mykhailivka kurgans, and of Maykop material in Lower Don and Donets Kurgans. Consequently, he refutes “an exclusively steppic origin” ; instead he sees monumental Kurgans to “reflect the transformation of the spiritual and social life of the steppe population (initially in elite groups) under the influence of the agricultural world“.

Let me finally add a few more examples of “kurganised” groups:

a. Neolithic Brittany (Carnac etc.), probably from the early 5th mBC onwards,

b. Baalberge (even named after a monumental burial mound), from around 4,000 BC onwards (albeit the mounds still lack dating)

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schneiderberg_(Baalberge)

c. Predynastic Egypt, with burial mounds in Naqada I (from ca. 4,000 BC) that evolved into Mastabas in Naqada II, and ultimately the Pyramids.

So, the phenomenon reached even further than just “Central Europe to Central Asia”. Increased mobility and trade certainly played a key role, albeit the emergence of monumental burial mounds seems to precede wheeled vehicles – it is initially probably rather about boats, and long-range pastoral migrations to salt sources/ marshes (e.g. Brittany, Moldova, Sea of Azov, Dead Sea).

PS: From the SupMats of the new Olalde paper (which I suppose you will want to take care of, Alberto), it looks like Cadiz, 4,300-3,700 BC, can be added to the list of “kurganised” cultures.

https://populationgenomics.blog/2019/03/14/steppe-maykop/

steatite beads are from india

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248579371_Steatite_beads_at_Peqi'in_Long_distance_trade_and_pyro-technology_during_the_Chalcolithic_of_the_Levant